Table of Contents

Attila the Hun Study Guide

Few names from antiquity evoke such immediate and visceral reactions as Attila the Hun. Known to history as the “Scourge of God,” Attila remains one of civilization’s most feared and misunderstood leaders—a figure whose very name became synonymous with devastation, yet whose actual historical impact extends far beyond simple destruction.

Ruling the Hunnic Empire at its peak from 434 to 453 CE, Attila commanded the most powerful force in Europe during the twilight years of the Western Roman Empire. His military campaigns stretched from the steppes of Central Asia to the heart of Gaul, from the Danube frontier to the gates of Rome itself. The terror he inspired was so profound that Christian leaders called him God’s instrument of divine punishment—a scourge sent to chastise a sinful world.

Yet Attila’s legacy transcends his reputation as a destroyer. His conquests accelerated the transformation of Europe from the classical Roman world into the medieval landscape of competing kingdoms. His invasions triggered massive population movements that redrew the ethnic and political map of the continent. His interactions with the Roman Empire, the Christian Church, and Germanic peoples shaped the course of Western civilization in ways that reverberate even today.

Understanding Attila the Hun means looking beyond the caricature of the bloodthirsty barbarian to examine a complex historical figure who wielded both military might and diplomatic cunning. It means exploring how the Huns rose from obscure nomadic origins to threaten the greatest empire of their age. And it means recognizing how fear, faith, and historical memory have transformed a 5th-century warlord into an enduring symbol of chaos and power.

This comprehensive guide examines Attila’s rise to power, his military campaigns and strategies, his cultural and religious impact, and the surprising ways his legacy has evolved across fifteen centuries. Whether you’re a student of history, a reader fascinated by Late Antiquity, or simply curious about one of history’s most notorious figures, this exploration of Attila the Hun will reveal why his name still resonates with such power today.

The Huns: Origins, Migrations, and the Rise of a Nomadic Empire

The Mysterious Origins of the Huns

The Huns burst into European consciousness suddenly and violently in the late 4th century CE, but their origins remain shrouded in mystery and scholarly debate. Most historians believe the Huns originated somewhere in the vast Eurasian steppes, possibly connected to the Xiongnu—nomadic warriors who had troubled China’s northern borders for centuries.

Chinese sources describe the Xiongnu as formidable mounted archers who posed a constant threat to settled civilizations, leading to the construction of early versions of the Great Wall. When Chinese military campaigns finally defeated the northern Xiongnu around 90 CE, some groups migrated westward, potentially forming the ancestral core of what would become the Huns.

The journey from the Asian steppes to Europe took centuries and involved complex interactions with numerous peoples along the way. By the time the Huns appeared in European records around 370 CE, they had absorbed various tribal groups, adopted new customs, and developed into a distinct confederation with their own identity and military culture.

Archaeological evidence reveals that the Huns practiced artificial cranial deformation—binding infants’ heads to create elongated skulls—a custom that marked them as culturally distinct and likely increased their fearsome reputation among peoples who encountered them. Their material culture shows influences from Persian, Chinese, and steppe traditions, indicating the Huns were not isolated primitives but participants in long-distance trade networks and cultural exchange.

The question of Hunnic origins matters because it shapes how we understand their society and capabilities. Far from being simple savages, the Huns drew on centuries of steppe warfare tradition, sophisticated horsemanship, and composite bow technology that gave them decisive military advantages over their European opponents.

The Great Migration: Huns Enter Europe

The Huns’ arrival in Europe triggered what historians call the Völkerwanderung or “Migration Period”—a cascade of population movements that fundamentally altered the continent’s demographic and political landscape. Around 370 CE, Hunnic armies swept into the territories north of the Black Sea, overwhelming the Alani and the Goths who had settled there.

The Gothic kingdoms, which had seemed powerful and stable, collapsed almost instantly before the Hunnic onslaught. The Ostrogoths (Eastern Goths) were subjugated and forced to provide troops for Hunnic armies. The Visigoths (Western Goths), desperate to escape Hunnic domination, petitioned the Roman Empire for permission to cross the Danube and settle within imperial territory.

Rome’s decision to allow these Gothic refugees across the frontier in 376 CE set in motion a chain of events with catastrophic consequences. Mistreated by Roman officials, the Goths rebelled, and in 378 CE, they defeated and killed the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople—one of Rome’s most devastating military disasters.

This pattern repeated across Europe. The Huns didn’t simply conquer territory in the traditional sense—they created waves of displacement that pushed other peoples into new lands, generating conflict and instability throughout the continent. Germanic tribes pressed against Roman frontiers with new urgency, some seeking refuge, others seeking opportunity in Rome’s apparent weakness.

By the early 5th century, the Huns had established themselves in the Carpathian Basin (modern Hungary) and the Danube Valley, creating a vast territory under their control. From this central position, they could threaten both the Eastern Roman Empire (centered on Constantinople) and the Western Roman Empire (with its capital at Ravenna after Rome became too vulnerable).

The Hunnic Military System: Why They Were So Effective

The Huns’ military effectiveness stemmed from several factors that gave them decisive advantages over the armies they faced:

Superior horsemanship: The Huns were essentially born in the saddle. Roman sources reported that Huns seemed to live on horseback—eating, sleeping, and conducting business without dismounting. This extraordinary equestrian skill gave them mobility that sedentary peoples simply couldn’t match.

The composite bow: The Hunnic composite bow was a technological marvel—short enough to use effectively from horseback yet powerful enough to penetrate armor at considerable distances. Made from layers of wood, horn, and sinew, these bows required years to construct and master but made Hunnic warriors deadly at ranges where Roman infantry couldn’t respond.

Tactical flexibility: Unlike Roman armies that relied on disciplined infantry formations, Hunnic forces used fluid cavalry tactics—feigned retreats, envelopment maneuvers, and hit-and-run attacks that frustrated opponents accustomed to set-piece battles. They could concentrate overwhelming force at decisive points, then disperse before enemies could mount effective counterattacks.

Psychological warfare: The Huns deliberately cultivated their fearsome reputation. Their appearance—including cranial deformation and facial scarification—was designed to intimidate. They emphasized speed and surprise, often appearing where least expected and creating panic that demoralized defenders before battle even began.

Multilingual and multicultural armies: By the time of Attila, Hunnic armies included warriors from numerous subjugated peoples—Goths, Gepids, Heruli, Alani, and others. This diversity provided specialized capabilities and allowed Hunnic leaders to exploit various peoples’ particular strengths.

Logistical advantages: Nomadic peoples travel light and live off the land more easily than sedentary armies. The Huns didn’t require the complex supply trains that Roman armies needed. Their horses could graze on grasslands, and their mobile lifestyle meant they could sustain campaigns where Roman forces would starve.

These military advantages made the Huns nearly invincible in open-field combat during their period of dominance. Only when defenders could leverage fortifications, exploit Hunnic weaknesses in siege warfare, or assemble coalition armies large enough to counter Hunnic mobility could they hope to resist successfully.

Attila’s Rise to Power: From Shared Rule to Supreme Leadership

Early Life and Ascension (Circa 434 CE)

Attila’s early life remains largely mysterious, as contemporary sources provide few details about his youth or education. We know he was born around 406 CE into the Hunnic royal family, positioned to inherit leadership but not initially the sole or obvious heir.

In 434 CE, the Hunnic Empire came under the joint rule of Attila and his brother Bleda following the death of their uncle Ruga (also called Rugila). Shared leadership wasn’t unusual in steppe empires, where power often distributed among multiple family members to balance different tribal factions and reduce succession conflicts.

Initially, Bleda and Attila seemed to cooperate effectively. They renegotiated treaties with the Eastern Roman Empire, demanding increased tribute payments and threatening renewed warfare if their demands weren’t met. The Romans, struggling with internal problems and conflicts on other frontiers, generally found it more economical to pay tribute than to fight.

The brothers led joint military campaigns against the Eastern Romans in the early 440s, striking deep into Balkan territories and capturing numerous fortified cities. These campaigns demonstrated both the Huns’ military power and the Romans’ inability to effectively defend their frontier regions.

The Death of Bleda and Attila’s Sole Rule

Around 445 CE, Bleda died under circumstances that ancient sources describe with suspicious vagueness. While some accounts suggest he died of natural causes or in battle, the overwhelming likelihood is that Attila had his brother murdered to consolidate power under his sole authority.

This ruthless elimination of a co-ruler wasn’t unusual in the brutal politics of the period. Shared rule created inefficiencies and potential conflicts. Attila apparently decided that unified command was necessary for the grand ambitions he envisioned for the Hunnic Empire.

Once sole ruler, Attila transformed the Hunnic confederation from a loose coalition of tribes into something more resembling a centralized empire. He imposed strict discipline, demanded absolute loyalty, and organized military campaigns with unprecedented scale and coordination.

Ancient sources describe Attila as austere in personal habits despite his vast power. While his subordinate chieftains ate from silver and gold plates, Attila reportedly ate from wooden dishes and dressed simply. Whether this austerity was genuine or calculated to project an image of warrior virtue, it contributed to his charismatic authority and the loyalty he commanded from his followers.

Leadership Style and Administrative Abilities

Attila wasn’t simply a brilliant military commander—he demonstrated considerable administrative and diplomatic capabilities that allowed him to hold together a diverse empire and extract maximum resources from both subjugated peoples and Roman tribute.

His leadership approach combined several elements:

Personal charisma and authority: By all accounts, Attila commanded through force of personality as much as through military power. Ambassadors who visited his court described a leader who could be generous or terrifying, who listened to advice but made final decisions unilaterally, and who inspired both loyalty and fear in equal measure.

Strategic use of terror: Attila understood that reputation could accomplish what armies could not. By cultivating a fearsome image and occasionally demonstrating overwhelming brutality, he ensured that many opponents preferred surrender or tribute to resistance.

Diplomatic sophistication: Despite his reputation as a barbarian destroyer, Attila engaged in complex diplomatic negotiations with Roman authorities, played different factions against each other, and understood how to exploit internal Roman conflicts to Hunnic advantage.

Meritocratic elements: While Hunnic society retained tribal hierarchies, Attila apparently promoted capable leaders regardless of their ethnic origin. His armies included commanders from Germanic and other backgrounds who had proven their abilities.

Balanced tribute and conquest: Attila recognized that extracting ongoing tribute from surviving states often provided more sustainable resources than outright conquest and occupation. He calibrated his military pressure to keep tribute flowing without completely destroying the sources of wealth.

This combination of military prowess, administrative capability, and strategic thinking made Attila’s rule the apogee of Hunnic power. Under his leadership, the Hunnic Empire controlled territories from the Rhine to the Ural Mountains, from the Baltic to the Balkans—a vast domain that made him arguably the most powerful ruler in Europe.

Major Military Campaigns: The Scourge of God at War

The Balkan Campaigns: Ravaging the Eastern Roman Empire

Attila’s first major campaigns as sole ruler targeted the Eastern Roman Empire (often called the Byzantine Empire by modern historians, though contemporaries still called it simply “Rome”). These Balkan campaigns in the 440s demonstrated the Huns’ military superiority and the Romans’ inability to defend their territories effectively.

In 441-442 CE, Attila’s forces swept through Roman territories along the Danube, capturing numerous fortified cities including Viminacium and Singidunum (modern Belgrade). The speed and violence of these attacks shocked Roman authorities, who had grown complacent about barbarian threats.

The Romans negotiated peace, agreeing to massive increases in tribute payments—from 350 pounds of gold annually to 2,100 pounds—and promised to return Hun refugees who had fled to Roman territory. These harsh terms demonstrated the Romans’ weakness and emboldened Attila to push for even greater concessions.

In 447 CE, Attila launched an even more devastating campaign, striking deeper into Roman territories. His armies captured over seventy cities in the Balkans, including major centers like Marcianopolis, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv), and Arcadiopolis. The Hunnic forces advanced to within sight of Constantinople itself, the great capital that had never fallen to foreign conquest.

The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II desperately negotiated another peace, agreeing to even more humiliating terms. Annual tribute increased to 2,100 pounds of gold, and the Romans had to pay arrears of 6,000 pounds for missed payments. Additionally, the Romans agreed to evacuate a five-day-journey zone south of the Danube, creating a buffer territory where the Huns could operate freely.

These campaigns accomplished several strategic objectives for Attila:

- They extracted enormous wealth that funded his empire and rewarded his followers

- They demonstrated Roman weakness, encouraging other peoples to challenge imperial authority

- They secured the Huns’ southern frontier, allowing Attila to turn his attention westward

- They established the Huns as the dominant power in Eastern Europe

The psychological impact was equally significant. The Romans, who had long viewed themselves as the civilized world’s protectors against barbarian chaos, now paid tribute to avoid destruction—a humiliation that undermined imperial prestige throughout the Mediterranean world.

The Gallic Campaign: Invasion of the Western Empire (451 CE)

Having thoroughly intimidated the Eastern Romans, Attila turned his attention to the Western Roman Empire in 450-451 CE. The immediate pretext involved a peculiar diplomatic incident with significant consequences.

Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, allegedly sent Attila a ring and a plea for help after being forced into an unwanted betrothal following a scandal. Attila claimed this constituted a marriage proposal and demanded half the Western Empire as Honoria’s dowry. Whether Attila genuinely believed this claim or simply used it as a convenient excuse for invasion, it provided a diplomatic pretext for his western campaign.

In 451 CE, Attila led perhaps the largest army ever assembled by the Huns—estimates range from 30,000 to 100,000 warriors, including numerous Germanic allies and subject peoples. This massive force crossed the Rhine and swept through Gaul (modern France and parts of Germany).

The Hunnic army captured or besieged numerous cities, including Metz, Reims, and Strasbourg. The scale of destruction was enormous. Archaeological evidence and contemporary accounts describe wholesale devastation—cities burned, populations massacred or enslaved, and entire regions depopulated.

Orléans became a crucial point of resistance. The city’s bishop, St. Anianus, rallied the defenders while desperately hoping for relief. As Attila’s forces prepared the final assault, a coalition army arrived just in time. This army, commanded by the Roman general Flavius Aetius and including Visigothic King Theodoric I, drove Attila away from Orléans and pursued his forces eastward.

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (451 CE)

The pursuit culminated in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (also called the Battle of Châlons), fought in June 451 CE near modern Châlons-en-Champagne, France. This battle ranks among Late Antiquity’s most significant military encounters, though details remain frustratingly unclear due to contradictory ancient sources.

The coalition facing Attila was itself impressive:

- Roman forces under Aetius, including regular legions and foederati (allied troops)

- Visigoths led by King Theodoric I, providing heavy cavalry

- Franks, Burgundians, Alans, and various other Germanic peoples

- Sarmatians and other groups with their own grievances against the Huns

Against this coalition, Attila commanded his own diverse army:

- Hunnic cavalry providing the shock force and mobility

- Ostrogoths and Gepids serving as subject allies

- Various Germanic and Alan contingents

- Possibly some Roman deserters and mercenaries

The battle itself was brutal and chaotic. Ancient sources provide widely varying casualty figures—some claiming 165,000 dead, others suggesting more modest but still horrific losses. What seems clear is that both sides committed fully, neither gained a decisive advantage, and the carnage was exceptional even by the standards of that violent age.

The Visigoths suffered the loss of King Theodoric I, killed during the fighting. His son Thorismund assumed command and wanted to pursue the Huns aggressively. However, Aetius, concerned about Visigothic power and preferring to maintain the Huns as a counterweight to other threats, allegedly discouraged further pursuit.

Attila withdrew in good order, his army still formidable despite the setback. The battle wasn’t a crushing defeat—more of a tactical stalemate that nonetheless achieved strategic success for the coalition. Attila’s invasion of Gaul was stopped, his aura of invincibility was damaged, and the Western Empire survived to fight another day.

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains holds enormous historical significance. Some historians argue it ranks among history’s most important battles—a clash that prevented Hunnic conquest of Western Europe and preserved the conditions for eventual medieval European civilization to emerge from Rome’s ruins.

The Italian Campaign: To the Gates of Rome (452 CE)

Despite his setback in Gaul, Attila wasn’t finished with the Western Empire. In 452 CE, he launched an invasion of Italy itself, crossing the Alps and descending into the Po River valley—the heartland of the Western Roman Empire.

The Italian campaign proceeded with devastating effectiveness. The great city of Aquileia, one of Italy’s wealthiest and most important centers, endured a lengthy siege before falling to Hunnic assault. Contemporary accounts describe the city’s destruction as so complete that later generations could barely identify where it had stood. Archaeological evidence confirms severe destruction levels consistent with these accounts.

Following Aquileia’s fall, other northern Italian cities surrendered or were captured in rapid succession:

- Concordia

- Altinum

- Patavium (modern Padua)

- Vicetia (modern Vicenza)

- Verona

- Brixia (modern Brescia)

- Bergomum (modern Bergamo)

- Mediolanum (modern Milan), one of the empire’s administrative capitals

The speed of these conquests panicked Roman authorities. Emperor Valentinian III fled from Ravenna to Rome, and there seemed little that could stop Attila from marching on Rome itself and delivering a final, humiliating blow to the Western Empire.

Then, something remarkable happened. As Attila’s forces approached the Po River, preparing to advance on Rome, a delegation arrived from the city led by Pope Leo I (later known as Leo the Great), accompanied by other senior officials and clergy.

The Meeting with Pope Leo I: Legend and Reality

The meeting between Pope Leo I and Attila the Hun has become one of history’s most famous encounters, wrapped in legend yet rooted in documented fact. What actually transpired during their conference remains somewhat mysterious, as contemporary sources provide only limited details.

According to the primary account by Prosper of Aquitaine, written shortly after the events, Pope Leo met Attila and successfully persuaded him to withdraw from Italy without attacking Rome. The encounter apparently took place near Mantua in northern Italy, on the banks of the Mincio River.

Later legends embellished the story considerably. Medieval accounts claimed that as Leo spoke, Attila saw a vision of St. Peter and St. Paul standing behind the Pope, wielding flaming swords and threatening divine vengeance if Attila continued. This miraculous vision supposedly terrified Attila into retreat.

While the supernatural elements are almost certainly legendary additions, the basic fact—that Leo’s embassy successfully convinced Attila to withdraw—is historically documented. But why did Attila agree? Several practical factors likely influenced his decision:

Disease: Italy was experiencing plague or epidemic disease. Attila’s army, suffering from illness, may have been in no condition for further campaigning. Historical sources mention disease affecting the Hunnic forces.

Supply problems: The Huns’ pastoral lifestyle and cavalry-dependent warfare required vast grasslands for horse grazing. Italy’s agricultural landscape and deforested regions made sustaining a large mounted army difficult.

Eastern threat: Emperor Marcian of the Eastern Roman Empire had reportedly sent forces to attack Hunnic territories while Attila was occupied in Italy. Attila may have needed to return to defend his homeland.

Tribute negotiations: Leo likely brought significant financial inducements—a substantial tribute payment that made withdrawal more attractive than the uncertain costs of besieging Rome.

Strategic calculation: Rome itself, while symbolically important, was no longer the Western Empire’s administrative or economic center. Ravenna served as the capital, and capturing Rome wouldn’t necessarily achieve decisive strategic objectives.

Superstition: Even without accepting miraculous visions, Attila may have been influenced by omens and superstitions. He reportedly knew that Alaric the Visigoth had died shortly after sacking Rome in 410 CE and may have feared a similar fate.

Whatever combination of factors motivated him, Attila withdrew from Italy in 452 CE without attacking Rome. Pope Leo returned to the city as a hero, credited with saving Rome through spiritual authority where military force had failed. This encounter significantly enhanced papal prestige and contributed to the medieval papacy’s claim to temporal as well as spiritual power.

Attila’s Death and the Immediate Collapse of His Empire

The Death of Attila (453 CE)

Attila’s death came suddenly and unexpectedly in 453 CE, cutting short his reign at the height of Hunnic power. The circumstances of his death, while well-documented in general outline, contain elements that have sparked speculation and debate.

According to the primary account by the historian Priscus (preserved in fragments by later writers), Attila died on his wedding night after marrying a young woman named Ildico. The evening involved the typical feasting and heavy drinking characteristic of Hunnic celebrations.

The next morning, when Attila didn’t emerge from his chambers, his attendants grew concerned. Eventually, they broke into the room and found Attila dead in a pool of blood, with his new bride sitting nearby in tears. There were no signs of violence or struggle.

The most likely explanation, accepted by most historians, is that Attila suffered a severe nosebleed (epistaxis) while unconscious from alcohol consumption, and he choked on his own blood. The historian Priscus reports this as the official cause of death. Romans of the time suffered from various medical conditions that could cause severe nosebleeds, including high blood pressure, and Attila’s lifestyle—marked by stress, warfare, and heavy drinking—would have predisposed him to such problems.

However, the dramatic timing—death on his wedding night—naturally sparked alternative theories:

Assassination by Ildico: Some have speculated that Ildico murdered Attila, perhaps as revenge for her people or under orders from Roman authorities. However, no contemporary source suggests this, and if murder had been suspected, Ildico would likely have been executed immediately.

Poisoning: Others have suggested poison, though again, contemporary sources don’t support this theory, and the physical evidence (blood in the room) better fits the nosebleed explanation.

Divine retribution: Christian writers naturally interpreted Attila’s sudden death as God’s judgment against the “Scourge of God,” suggesting divine intervention rather than natural causes.

The most striking aspect of Attila’s death was how sudden and anticlimactic it was. This seemingly invincible conqueror, who had terrorized empires and commanded the most powerful army in Europe, died not in battle or in old age but in an almost absurd accident involving too much alcohol and an unfortunate nosebleed.

The Funeral and Succession Crisis

Attila’s funeral, described by Priscus in detail, reflected the Huns’ cultural traditions and the enormity of the loss:

His body was enclosed in three nested coffins—first gold, then silver, then iron—symbolizing his conquest of precious metals and his iron will. The coffins were buried in a secret location along with treasures from his conquests. The workers who dug the grave and knew its location were reportedly killed to ensure the secret remained hidden. To this day, despite numerous searches and archaeological investigations, Attila’s burial site has never been conclusively identified.

The Huns held elaborate funeral games and feasts, with warriors cutting themselves to mourn their leader properly—grieving with blood rather than tears, as befitted a warrior culture. The funeral celebrations reportedly lasted for days.

But even as they mourned, succession disputes began tearing the empire apart. Attila had left numerous sons by multiple wives and concubines, and no clear succession plan existed. The eldest sons—Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernak—claimed authority, but none possessed their father’s charisma, military genius, or ability to hold the diverse confederation together.

The Rapid Disintegration of the Hunnic Empire

The Hunnic Empire’s collapse was remarkably swift, demonstrating how much Attila’s personal authority had held it together. Within a year of his death, the empire was fragmenting.

The subject peoples, who had chafed under Hunnic domination, saw their opportunity. The Gepids, led by their king Ardaric, formed a coalition of Germanic peoples including Ostrogoths, Heruli, Rugii, and Sciri. This coalition challenged Hunnic authority at the Battle of Nedao in 454 CE (the exact location remains uncertain, somewhere in Pannonia).

The Battle of Nedao resulted in a decisive defeat for the Huns. Ellac, Attila’s eldest son and designated successor, was killed in the fighting. The Germanic coalition shattered Hunnic military dominance in a single engagement, reversing in one day what had taken decades to establish.

Following this defeat, the Hunnic Empire rapidly disintegrated:

- The Gepids claimed much of the Carpathian Basin

- The Ostrogoths regained independence and eventually moved into Italy

- Various Germanic tribes established independent kingdoms in former Hunnic territories

- The remaining Huns fragmented into smaller groups

Some Hunnic remnants retreated eastward toward the steppes, where they were absorbed into other nomadic populations or simply disappeared from historical records. Other groups remained in Eastern Europe as minor players, occasionally appearing in historical sources but never regaining their former power.

By 469 CE, less than two decades after Attila’s death, the last significant Hunnic leader, Dengizich (another of Attila’s sons), was defeated and killed by Roman forces. His head was displayed in Constantinople as a trophy, symbolically ending the Hunnic threat that had terrorized Europe for generations.

The rapidity of this collapse teaches important historical lessons about charismatic leadership, imperial consolidation, and the challenges of succession. Attila had created an empire based largely on his personal authority and military genius rather than on stable institutions, clear succession mechanisms, or genuine cultural unity. When he died unexpectedly, there was no foundation strong enough to preserve what he had built.

Cultural and Religious Impact: The Scourge of God in Context

The “Scourge of God”: Christian Interpretations

The title “Flagellum Dei” or “Scourge of God” has become so associated with Attila that many assume he claimed it for himself. In reality, this designation came from Christian writers trying to make theological sense of the devastation the Huns inflicted.

The concept of divine punishment through foreign invaders had deep roots in Judeo-Christian tradition. The Hebrew Bible repeatedly describes conquering armies as instruments of God’s judgment against sinful nations. When Jerusalem fell to Babylon in 586 BCE, prophets interpreted this as God punishing Israel for abandoning true worship. This theological framework provided Christians with a way to understand catastrophic events without abandoning faith in divine providence.

When the Huns appeared, bringing unprecedented destruction, Christian theologians naturally reached for this interpretive framework. Writers like Prosper of Aquitaine, Hydatius, and Cassiodorus described Attila as God’s tool for punishing Christian sins—moral corruption, doctrinal disputes, persecution of the righteous, and worldly attachment to wealth and power.

This interpretation served several theological purposes:

Theodicy: It explained why a good God would allow such terrible suffering. The Huns weren’t a failure of divine power or care—they were its instrument.

Moral exhortation: By framing Hunnic invasions as punishment for sin, church leaders could call Christians to repentance, reform, and renewed devotion.

Ecclesiastical authority: The church positioned itself as the necessary intermediary between sinful humanity and divine judgment. Only through the church’s guidance could society avoid future scourges.

Making sense of survival: Cities and regions that escaped Hunnic destruction could attribute their survival to divine favor earned through piety, explaining differential outcomes without admitting random chance.

Pope Leo I’s successful embassy to Attila reinforced these interpretations. If Attila was indeed God’s scourge, then Leo’s success in turning him away demonstrated the spiritual power of the church—specifically papal authority—in ways that military force could not. This event significantly contributed to the medieval papacy’s growing temporal claims.

The irony is that Attila himself was likely unaware of or indifferent to this theological framing. He wasn’t a Christian seeking to punish Christian sins—he was a pragmatic ruler pursuing strategic objectives. Yet the “Scourge of God” label stuck, shaping how Western civilization remembered him for the next fifteen centuries.

The Völkerwanderung: Transformation of Europe’s Ethnic Landscape

Attila’s military campaigns accelerated the Völkerwanderung (Migration Period or Barbarian Invasions)—a complex series of population movements that fundamentally transformed Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. While the migrations began before Attila and continued after his death, his actions represented the high-water mark of the chaotic forces reshaping the continent.

The chain reaction worked roughly like this:

Hunnic pressure → Germanic displacement → Roman frontier breach → Settlement within former Roman territories → New kingdoms emerge

When the Huns arrived in Eastern Europe, they displaced the Goths, who in turn pushed into Roman territory. The Romans’ inability to effectively manage these migrations led to Gothic settlements that eventually became independent kingdoms. The Visigoths established a kingdom in Gaul and later Iberia. The Ostrogoths would eventually rule Italy itself after deposing the last Western Roman Emperor.

But the Goths were just one example. Attila’s campaigns and the general instability he created encouraged numerous peoples to move:

The Vandals, already in motion, crossed from Iberia into North Africa, establishing a kingdom that controlled the Mediterranean’s western basin and even sacked Rome in 455 CE.

The Burgundians established a kingdom in eastern Gaul (the Rhône valley), creating a political entity that would influence the region for centuries.

The Franks, taking advantage of Roman weakness, expanded from their Rhineland territories to eventually control most of Gaul, creating the foundation for modern France.

The Anglo-Saxons migrated from continental Europe to Britain in greater numbers as Roman Britain collapsed, fundamentally changing the island’s linguistic and cultural character.

The Lombards, initially allies of the Huns, later moved into Italy (568 CE), establishing yet another Germanic kingdom in former Roman territories.

These movements weren’t simple military conquests—they involved entire peoples migrating with families, livestock, and possessions, seeking new lands where they could establish permanent settlements. The demographic impact was enormous, creating the ethnic and linguistic diversity that still characterizes modern Europe.

The Roman Empire’s inability to resist or effectively manage these migrations demonstrated the empire’s terminal weakness. The Western Roman Empire formally ended in 476 CE when the Germanic general Odoacer deposed the last emperor, but in many ways, this was merely formalizing a situation that Attila’s campaigns had made inevitable decades earlier.

Christianity Versus Paganism in the 5th Century

Attila’s era marked a crucial period in the contest between Christianity and traditional pagan religions for control of European religious life. While Constantine the Great had legalized Christianity in 313 CE and Theodosius I had made it the Roman Empire’s official religion in 380 CE, paganism remained widespread, particularly in rural areas and among the Germanic peoples.

The Huns themselves practiced shamanistic paganism, venerating natural forces, ancestor spirits, and various deities. Their religious practices included animal sacrifice, divination through reading omens, and reverence for sacred swords and other objects believed to possess supernatural power. Some sources suggest Attila claimed to possess the “Sword of Mars”—a sacred weapon supposedly discovered by a shepherd and delivered to Attila, conferring divine favor and destined victory.

Many Germanic peoples remained pagan or had only recently converted to Christianity—often to Arianism, a Christian heresy that denied Christ’s full divinity and was officially condemned by the Catholic Church. The religious landscape was complex:

- Roman populations were predominantly Catholic Christian

- Visigoths were Arian Christians

- Ostrogoths were Arian Christians

- Franks were initially pagan but converted to Catholic Christianity under King Clovis (around 496 CE)

- Anglo-Saxons remained pagan until gradual conversion beginning around 597 CE

- Huns remained pagan throughout Attila’s reign

This religious diversity complicated political and military alliances. Theological differences between Catholic and Arian Christians sometimes proved as divisive as the gap between Christians and pagans. The Catholic Church used Attila’s invasions to argue that divine punishment targeted both pagans and heretics, reinforcing orthodox Catholic authority.

The crisis also prompted intensified Christian evangelization efforts. As traditional Roman order collapsed, the church increasingly filled the vacuum, providing social services, maintaining some degree of literacy and education, and offering spiritual meaning amid material catastrophe. Bishops became civic leaders, organizing defense, negotiating with invaders, and caring for refugees—roles that enhanced ecclesiastical authority and accelerated Christianization.

Attila himself seems to have been religiously tolerant in a pragmatic sense. His empire included Christians, Jews, and followers of various pagan traditions. As long as subjects provided tribute and military service, Attila apparently didn’t care about their private beliefs. This tolerance was pragmatic rather than principled—maintaining control over a diverse empire required avoiding religious conflicts that might provoke rebellion.

The Role of Superstition, Omens, and Prophecy

Both Romans and Huns took supernatural signs seriously, and these beliefs influenced strategic decisions during Attila’s campaigns. The 5th century was an age when even educated people believed divine forces directly influenced human affairs through portents, omens, and miraculous interventions.

Several episodes illustrate this mindset:

The Sword of Mars: The legend that Attila possessed a sacred sword discovered by divine providence served important propaganda purposes. It suggested that Attila’s conquests reflected divine favor rather than mere human ambition, legitimizing his rule and intimidating opponents who believed supernatural forces supported him.

Prophecies and dreams: Ancient sources report various prophecies and visions surrounding Attila. Some claimed that seers predicted his victories, while others reported dreams warning of his death. Whether these reports were genuine beliefs or later inventions, they reflect how both sides tried to claim supernatural authority for their positions.

Interpreting natural phenomena: Eclipses, comets, earthquakes, and unusual weather were seen as divine communications. Both Romans and Huns interpreted such events as favorable or unfavorable omens, sometimes delaying or accelerating military operations based on these readings.

St. Peter and St. Paul vision: The legend that Attila saw a vision of these saints threatening him during his meeting with Pope Leo I reflects the Christian belief that divine intervention actively shaped historical events. Whether Attila saw anything or simply made a pragmatic decision, Christians interpreted the outcome as miraculous.

Attila’s awareness of Alaric’s fate: Some sources suggest Attila refrained from sacking Rome partly because Alaric the Visigoth had died shortly after sacking the city in 410 CE. If true, this shows how superstitious beliefs could influence even hardened military leaders’ strategic calculations.

This supernatural worldview seems foreign to modern secular thinking, but it was utterly real to 5th-century people. Both Christianity and paganism agreed that divine forces shaped earthly events—they disagreed only about which gods or God controlled these forces and how to interpret their messages.

Lasting Historical Impact: How Attila Changed Europe

The Accelerated Fall of the Western Roman Empire

While the Western Roman Empire’s decline had numerous causes accumulating over centuries, Attila’s invasions dramatically accelerated the final collapse. Before the Hunnic campaigns, the Western Empire, though weakened, still maintained some administrative coherence and military capability. After Attila, collapse seemed inevitable.

The empire’s financial exhaustion was critical. Massive tribute payments to the Huns—combined with the costs of military campaigns, refugee management, and economic disruption—drained imperial coffers. Tax revenues declined as productive regions were devastated or lost to invaders. The government could no longer pay its armies adequately, leading to declining military effectiveness and increased reliance on unreliable barbarian foederati.

The loss of provinces undermined the empire’s economic and military foundations. North Africa’s loss to the Vandals (442 CE) deprived Rome of crucial grain supplies. Gaul’s effective independence under local warlords and Germanic kingdoms removed another major tax base. Hispania fragmented into competing powers. By the 450s, the Western Empire directly controlled little beyond Italy itself—and even Italy wasn’t entirely secure.

Perhaps most importantly, Attila’s campaigns shattered the myth of Roman invincibility. For centuries, Rome had represented order, civilization, and military superiority. Barbarians might raid frontiers but couldn’t truly threaten Rome itself. Attila changed this perception fundamentally. By extorting tribute, devastating provinces with impunity, and marching through Italy almost unopposed, he demonstrated that Rome was now weak—a realization that encouraged every ambitious barbarian king to try his own luck.

When the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed in 476 CE by the Germanic general Odoacer, it was almost anticlimactic. The empire had effectively ceased to function years earlier. Attila didn’t personally destroy the Western Roman Empire, but his campaigns represented the point when decline became irreversible collapse.

The Foundation of Medieval European Kingdoms

The population movements and political chaos generated by the Hunnic invasions created the conditions from which medieval European kingdoms emerged. The various Germanic peoples who settled in former Roman territories gradually established stable kingdoms that would define European political geography for centuries:

The Frankish Kingdom: The Franks, expanding during the chaos of the mid-5th century, eventually controlled most of Gaul and western Germany. Under the Carolingian Dynasty, particularly Charlemagne (768-814 CE), the Franks created an empire spanning much of Western Europe. This empire ultimately fragmented into the foundations of modern France and Germany.

The Visigothic Kingdom: The Visigoths, displaced by the Huns, established a kingdom in Iberia that lasted until the Islamic conquest (711 CE). Their legal traditions and administrative structures influenced later medieval Spanish kingdoms.

The Ostrogothic Kingdom: After regaining independence following Attila’s death, the Ostrogoths eventually conquered Italy under Theodoric the Great (493-526 CE), creating a sophisticated kingdom that preserved much Roman culture while remaining Germanic in identity.

The Vandal Kingdom: The Vandals’ North African kingdom (435-534 CE) controlled crucial Mediterranean territories until conquered by Byzantine Emperor Justinian, but their impact on regional development was significant.

Anglo-Saxon England: The migrations to Britain intensified during this period of continental chaos, creating the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that would eventually unite into England.

These kingdoms weren’t simply barbarian replacements for Roman order—they represented creative syntheses of Germanic and Roman traditions. Germanic kings adopted Roman administrative techniques, law codes, and urban infrastructure while maintaining Germanic military traditions, social structures, and legal customs. The resulting fusion created distinctively medieval forms of governance that differed from both their Germanic and Roman precedents.

The Catholic Church played a crucial role in this transition. As secular Roman authority collapsed, ecclesiastical structures remained intact, providing continuity, literacy, and legitimacy to the new Germanic rulers. Many Germanic kings converted to Catholicism partly to gain church support and access to Roman administrative expertise preserved by clergy.

This complex transformation—from unified Roman Empire to diverse Germanic kingdoms, from classical antiquity to the early Middle Ages—was set in motion by the migrations and invasions that Attila’s campaigns exemplified and accelerated.

Military and Strategic Legacy

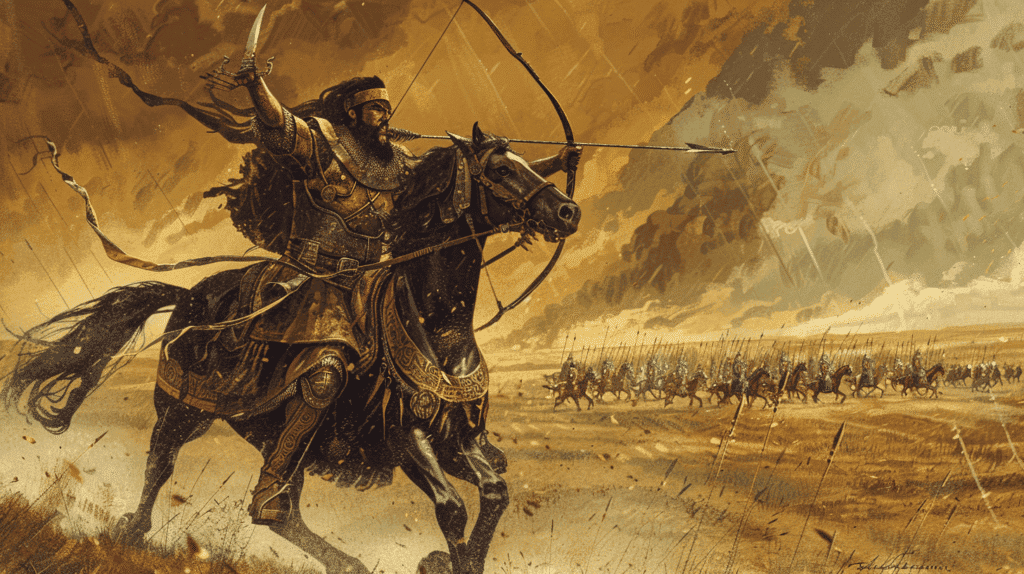

Attila’s military methods and strategic approaches influenced warfare for centuries, particularly the effective use of cavalry, psychological warfare, and the integration of diverse forces:

Cavalry emphasis: The Hunnic demonstration of mobile cavalry’s effectiveness against infantry-heavy armies influenced medieval European warfare. Heavy cavalry—armored knights on horseback—became the dominant military force in medieval Europe, a development partly inspired by the shock of Hunnic cavalry’s effectiveness.

Composite armies: Attila’s ability to coordinate forces from numerous peoples with different fighting styles demonstrated advantages of diversity when properly managed. Medieval armies similarly combined various troop types—heavy cavalry, light cavalry, infantry, archers—recognizing that tactical flexibility provided advantages.

Psychological warfare: Attila’s deliberate cultivation of a terrifying reputation influenced later military leaders. The recognition that fear could accomplish strategic objectives without fighting shaped medieval siege warfare, raiding tactics, and even heraldry and battle cries designed to intimidate opponents.

Speed and surprise: The Hunnic emphasis on rapid movement and unexpected attacks influenced medieval raiding tactics, particularly those of steppe peoples like the Magyars (Hungarians) and Mongols who later invaded Europe using similar methods.

Intelligence gathering: Attila’s extensive use of spies and scouts to gather information before campaigns demonstrated the strategic value of intelligence—a lesson not lost on later military commanders.

Military theorists have compared Attila to later great commanders like Genghis Khan and Subutai, noting similarities in their cavalry-based warfare, use of psychological tactics, and ability to coordinate diverse forces. The recognition that Attila’s methods weren’t simply barbaric but represented sophisticated military thinking has grown as historians have studied steppe warfare more carefully.

Attila’s Reputation and Legacy Across the Centuries

Medieval Perceptions: Destroyer or Legendary Ancestor?

Medieval European views of Attila varied dramatically depending on region and cultural tradition, revealing how historical memory serves different communities’ needs:

Western European Christian tradition generally remembered Attila as the archetypal barbarian destroyer—the Scourge of God who brought divine punishment but ultimately was turned back by Christian virtue (specifically Pope Leo I’s spiritual authority). Medieval chronicles, saints’ lives, and church histories reinforced this image, using Attila as a cautionary symbol of God’s judgment and the church’s protective power.

Medieval art depicted Attila in fearsome terms. Frescoes in Italian churches sometimes showed him as a literally demonic figure, while illustrations in chronicles portrayed him leading hordes of bestial warriors. These images served pedagogical purposes, teaching Christian audiences about divine punishment and the church’s role in protecting civilization.

Germanic traditions were more complex. Some Germanic peoples remembered the Huns as ancestral enemies who had dominated and oppressed their ancestors. The Nibelungenlied, a great Germanic epic poem (13th century), includes the Huns as significant characters, with Attila (called “Etzel” in German) appearing as a powerful but ultimately tragic figure whose court becomes the site of catastrophic destruction.

However, the Burgundian tradition preserved in the Nibelungenlied portrayed Attila somewhat sympathetically—as a reasonable, even generous ruler. This suggests that memories of Hunnic rule weren’t uniformly negative; some Germanic peoples remembered periods of stability and success under Hunnic dominance.

Hungarian tradition took yet another direction, claiming Attila as a national ancestor and hero. The Magyars, who arrived in the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century (centuries after the Huns), developed legends linking themselves to the Huns, with Attila as a glorious predecessor. Hungarian chronicles and popular traditions celebrated Attila as a mighty conqueror who had made Hungary feared throughout Europe.

This Hungarian claim is almost certainly historically false—the Magyars and Huns were distinct peoples with different origins, languages, and cultures. Yet the legend served important nation-building purposes, providing Hungarians with an ancient pedigree and heroic founder figure who legitimized their presence in Central Europe.

The Hungarian language preserves this connection through personal names (Attila remains a popular Hungarian name), place names, and national symbolism. Whether historically accurate or not, the association between Attila and Hungary became so deeply embedded in national identity that it remains a point of pride for many Hungarians today.

Renaissance and Early Modern Views

The Renaissance brought renewed interest in classical texts and more critical historical analysis, affecting Attila’s reputation in complex ways:

Humanist scholars studied ancient sources more carefully, attempting to separate legendary embellishments from historical facts. This scholarship gradually created a more nuanced picture of Attila as a real historical figure rather than a simple morality tale’s villain.

However, Renaissance and early modern uses of Attila’s image often served contemporary political purposes. Rulers wanting to emphasize their own power or intimidate enemies might invoke Attila’s name. Conversely, political opponents might label rulers they opposed as “new Attilas,” suggesting tyrannical brutality.

Artistic representations during this period varied considerably. Some artists portrayed Attila in traditional terms as a barbarian destroyer, particularly in works celebrating Christian triumph over paganism. Raphael’s famous fresco The Meeting between Leo the Great and Attila (1514) in the Vatican shows a clearly dominant Pope confronting a visibly overawed Attila with St. Peter and St. Paul appearing in the clouds—classical Christian triumphalism.

Other Renaissance artists showed more interest in Attila as an exotic historical figure, depicting his court, his appearance, and his campaigns with attention to historical detail (or at least period assumptions about such details) rather than purely theological messaging.

Early modern historians like Edward Gibbon (The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1776-1789) presented Attila within a broader analytical framework examining Rome’s collapse. Gibbon portrayed Attila as a significant but not unique barbarian leader—one of many factors contributing to imperial decline rather than a supernatural scourge. This more secular, analytical approach gradually displaced purely theological interpretations, at least among educated audiences.

19th and Early 20th Century: Nationalism and Romanticism

The 19th century brought new frameworks for understanding Attila, shaped by nationalism, romanticism, and emerging historical disciplines:

Nationalist movements across Europe selectively appropriated or rejected Attila depending on how he fit their national narratives. Hungarians continued claiming him as an ancestor. Some Turkish nationalists tried to claim connections to the Huns, seeing them as Turkic peoples (a linguistically and historically questionable claim). Germanic peoples generally rejected Attila as a foreign oppressor but sometimes romanticized the Gothic and other Germanic peoples who resisted him.

Romantic literature and art found Attila fascinating as a figure of passionate, untamed power. The Romantic movement’s interest in exotic, “barbarian” vigor as a counterweight to what they saw as effete, decadent civilization made Attila an appealing subject. Operas, poems, plays, and novels featuring Attila proliferated during this period.

Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Attila (1846) is the most famous musical treatment, presenting a romanticized but relatively sympathetic portrayal of the Hun leader as a complex figure driven by ambition and passion rather than simple brutality.

Late 19th-century racial theories unfortunately incorporated Attila into pseudo-scientific frameworks about race and civilization. Some writers used the Huns as examples of “Asiatic” racial threats to “European” civilization—pernicious racialist thinking that would have tragic consequences in the 20th century.

During World War I, Allied propaganda revived “Hun” as an epithet for Germans, drawing on centuries-old fears of Attila. This usage was deeply ironic given that the historical Huns had oppressed Germanic peoples and that Germans themselves had fought the Huns. Nonetheless, the propaganda proved effective, demonstrating Attila’s continued symbolic power to evoke barbarism and destructive violence.

Modern Historical and Archaeological Perspectives

Contemporary scholarship has developed increasingly sophisticated understandings of Attila and the Huns, moving beyond simple condemnation or romanticization:

Archaeological evidence has gradually accumulated, revealing more about Hunnic material culture, burial practices, settlement patterns, and daily life. Excavations in former Hunnic territories have uncovered graves, artifacts, and settlements that complicate earlier assumptions about the Huns as purely nomadic raiders.

These discoveries reveal that Hunnic society was more complex than simple pastoral nomadism. They engaged in metallurgy, pottery production, and some agriculture alongside their traditional horse-breeding and herding. They developed sophisticated hierarchies, accumulated wealth, and participated in long-distance trade networks connecting the Roman world with Central Asia and even China.

Linguistic analysis has helped scholars understand Hunnic origins and connections, though conclusively identifying the Hunnic language remains impossible due to limited evidence. Most scholars now believe the Huns spoke a Turkic language and originated somewhere in the Central Asian steppes, though certainty remains elusive.

Comparative studies of steppe nomadic empires have provided useful frameworks for understanding the Huns. Comparing Hunnic practices with those of the Xiongnu, the Göktürks, and especially the Mongols reveals common patterns in how nomadic peoples organized, fought, and interacted with sedentary civilizations. These comparisons help explain Hunnic success and their empire’s rapid collapse.

Postcolonial and critical perspectives have questioned earlier narratives that uncritically adopted Roman viewpoints, portraying “civilized” Romans against “barbaric” Huns. Modern scholars recognize that Roman sources were biased, often exaggerating Hunnic cruelty while downplaying Roman atrocities. The Huns, from their own perspective, were pursuing rational strategic objectives, and their society possessed its own sophisticated cultural traditions deserving of respect.

Interdisciplinary approaches combining history, archaeology, genetics, linguistics, and climate studies have revealed that population movements during this period responded to complex factors including climate change, resource competition, disease, and political opportunities. The Huns weren’t simply irrational destroyers but rational actors responding to environmental and political circumstances.

Attila in Popular Culture: From History to Mythology

Modern popular culture has embraced Attila as an enduringly fascinating figure, though representations range from historical to wildly fantastical:

Historical fiction has produced numerous novels featuring Attila, from serious attempts at historical accuracy to pulp adventures. These works often humanize Attila, exploring possible psychological motivations and presenting him as a complex character rather than a simple villain.

Film and television have depicted Attila numerous times. Attila (2001), a television miniseries starring Gerard Butler, presented a relatively nuanced portrayal showing both Attila’s brutality and his strategic intelligence. Other films have ranged from historical epics to campy B-movies to comedic treatments.

Video games, particularly historical strategy games, frequently feature Attila. Total War: Attila (2015) allows players to command Hunnic forces or defend against them, while Age of Empires II and Civilization series include Attila as a leader or historical scenario. These games often simplify complex history but introduce millions of players to Attila’s story.

Comics and graphic novels have adapted Attila’s life, often emphasizing action and violence but sometimes exploring deeper themes about power, civilization, and cultural conflict.

Heavy metal and hard rock bands have written numerous songs about Attila, drawn to themes of warfare, power, and rebellion against Rome. The name “Attila” itself appears in band names, album titles, and song lyrics across the metal genre.

This popular culture presence demonstrates Attila’s continued relevance as a symbol. He represents themes that resonate across generations: the clash of civilizations, the limits of imperial power, the role of charismatic leadership, the thin line between civilization and chaos, and the unpredictability of history.

Additional Resources for Understanding Attila the Hun

For readers interested in exploring Attila and the Hunnic Empire more deeply, several resources provide scholarly and accessible information:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection on Migration Period art includes artifacts from Hunnic and related cultures, offering visual evidence about material culture and artistic traditions of this transformative period.

UNESCO World Heritage sites related to Late Antiquity and the Migration Period provide archaeological context for understanding the physical remains of this era and the transformation of European landscapes.

Conclusion: Attila the Hun Study Guide

Fifteen centuries after his death, Attila the Hun remains a figure of enduring fascination and continuing controversy. His historical impact is undeniable—his military campaigns accelerated the Western Roman Empire’s collapse, triggered population movements that reshaped Europe’s ethnic landscape, and demonstrated the vulnerability of seemingly invincible imperial power.

Yet understanding Attila requires moving beyond simple narratives of barbarian destruction. He was neither the demonic scourge of Christian legend nor the romanticized noble savage of 19th-century imagination. He was a brilliant military commander who understood cavalry warfare, psychological intimidation, and strategic positioning. He was a pragmatic ruler who held together a diverse empire through a combination of fear, reward, and personal charisma. He was a diplomatic sophisticate who understood how to exploit Roman internal conflicts and extract maximum tribute with minimal fighting.

His legacy is complex and contradictory. Western European Christians remembered him as the Scourge of God—divine punishment for sin. Hungarians claimed him as a national hero and ancestral founder. Germans saw him as an oppressor of their Gothic ancestors. Modern historians recognize him as a pivotal figure in Late Antiquity whose actions helped transform the ancient world into medieval Europe.

The rapid collapse of his empire after his death reveals both his personal genius and the limitations of charismatic leadership. Attila created a vast realm but failed to establish institutions, succession mechanisms, or genuine unity that could survive his passing. Within two decades of his death, the Hunnic Empire had vanished so completely that later generations struggled to locate even his burial site.

Perhaps the most important lesson from Attila’s story is how profoundly fear can shape history. The terror he inspired influenced Roman policy, accelerated Germanic migrations, and affected decisions across Europe. Even today, his name evokes immediate associations with destruction and barbarism—a testament to the psychological impact of his campaigns.

Yet Attila’s story also reminds us of historical contingency and the limits of power. His sudden death from a nosebleed—one of history’s most anticlimactic endings—demonstrates that even the most fearsome conqueror remains vulnerable to chance, biology, and mortality. The mighty Scourge of God died not in glorious battle but in an almost absurd accident, and his empire died with him.

Understanding Attila means recognizing that history is neither a simple story of civilization versus barbarism nor a tale of inevitable progress. It’s a complex narrative of competing powers, adaptive strategies, unintended consequences, and the enduring impact of individuals whose actions ripple through centuries. Attila shaped the world we inherited—and his shadow, whether as destroyer or legend, extends across fifteen hundred years to touch us still.