Table of Contents

Who Are The Agoge? How Sparta Trained Its Children for War

Imagine being torn from your mother’s arms at age seven, never to live at home again. Your childhood ends in an instant, replaced by a life of deliberate hardship, constant competition, and systematic brutality. You’ll sleep on reeds you gathered yourself, wear a single cloak in both summer and winter, and endure beatings for the slightest error. You’ll be kept perpetually hungry, forced to steal to survive—then beaten if you’re caught.

This wasn’t punishment or abuse. This was education, Spartan-style.

The Agoge (ἀγωγή)—Sparta’s state-controlled training system—was perhaps the most extreme educational institution in Western history. For nearly 200 years, it transformed Spartan boys into the ancient world’s most feared warriors. It created soldiers who stood firm at Thermopylae, who never retreated, who sang as they marched into battle.

But the Agoge was far more than military training. It was total social engineering—a comprehensive system designed to erase individuality, suppress emotion, and create absolute loyalty to the state. It shaped not just soldiers but an entire civilization built on discipline, conformity, and martial excellence.

Why did Sparta create such an extreme system? How did it actually work? What happened to the boys who endured it? And what can this ancient institution teach us about education, military training, and the price of creating a warrior society?

This comprehensive guide explores every aspect of the Agoge—from its historical origins to its daily brutalities, from the psychological mechanisms that made it effective to its ultimate legacy. Whether you’re a student of ancient history, a military professional studying training methods, or simply curious about one of history’s most fascinating educational experiments, this guide reveals the complete story of how Sparta forged its legendary warriors.

Historical Context: Why Sparta Needed the Agoge

To understand the Agoge, you must first understand the unique—and precarious—situation that shaped Spartan society.

Sparta’s Helot Problem: The Foundation of Fear

Sparta’s entire social structure rested on a terrifying foundation: the helots (εἵλωτες).

Who were the helots?

The helots were a conquered population, primarily descendants of the Messenians whom Sparta subjugated in brutal wars (late 8th and 7th centuries BCE). Unlike typical ancient slaves, helots weren’t foreigners purchased in slave markets—they were Greeks, living on their ancestral lands, who had been reduced to permanent servitude by Spartan conquest.

The mathematical nightmare: Helots vastly outnumbered Spartans, possibly by ratios of 7:1 or even 10:1. Ancient sources suggest there may have been only 8,000-10,000 Spartan citizens (Spartiates) at the height of Spartan power, controlling perhaps 70,000-100,000 helots.

The constant threat: Helots worked Spartan lands, producing the food that allowed Spartans to train full-time for war. But their subjugation was enforced through terror:

- Annual declarations of war on the helots, making their killing legal

- State-sanctioned night raids (krypteia) to intimidate and eliminate potential leaders

- Public humiliation rituals (forced drunkenness, beatings) to psychologically crush resistance

- Brutal reprisals for any sign of rebellion

The fundamental paranoia: Spartans lived in constant fear of helot uprising. Historical sources record major helot revolts, particularly after earthquakes or military defeats when Spartan control weakened. The most serious revolt (c. 464 BCE) required years to suppress and nearly destroyed Sparta.

The Agoge connection: This demographic reality explains the Agoge’s brutality. Sparta didn’t just need soldiers—it needed a warrior class capable of suppressing a vast, hostile population through absolute military superiority and the willingness to use systematic violence. Every Spartan had to be a soldier because internal security depended on it.

The Spartan Social Structure

Understanding the Agoge requires grasping Sparta’s unique social hierarchy:

Spartiates (Full citizens):

- Male Spartan citizens who completed the Agoge

- The warrior elite, approximately 8,000-10,000 at peak

- Prohibited from labor, trade, or most professions

- Required to participate in communal mess halls (syssitia) and maintain military readiness

- Only class with full political rights

Perioikoi (“dwellers around”):

- Free non-citizens living in surrounding communities

- Could own land and engage in commerce

- Served in the military but lacked political rights

- Artisans, merchants, and craftsmen

Helots:

- Conquered population in permanent servitude

- Tied to specific land plots, working them for Spartan masters

- Could not be sold individually but were transferred with land

- No legal rights, subject to arbitrary violence

This rigid hierarchy meant Spartiates were a tiny, isolated elite whose survival depended on absolute military superiority and internal cohesion—exactly what the Agoge was designed to create.

The Evolution of the Agoge

The Agoge didn’t emerge fully formed—it evolved as Sparta responded to historical challenges:

Pre-Agoge period (before c. 650 BCE):

Early Sparta was relatively normal by Greek standards. Archaeological evidence shows a flourishing arts culture, poetry (Sparta produced famous poets like Tyrtaeus), and social patterns similar to other Greek city-states.

The crisis period (c. 650-600 BCE):

Several factors converged to transform Sparta:

- Second Messenian War (c. 685-668 BCE): A desperate helot revolt that nearly succeeded, traumatizing Spartan society

- Military defeats: Losses to Argos and others revealed weaknesses in traditional Greek warfare

- Internal instability: Social tensions between rich and poor threatened civil war

The Lycurgan reforms (attributed to legendary lawgiver Lycurgus, possibly mythical):

Whether Lycurgus existed or is a convenient attribution for gradual changes, a comprehensive social reorganization occurred around 600 BCE, including:

- Land redistribution creating equality among Spartiates

- Prohibition of gold and silver currency (iron bars only)

- Mandatory communal dining (syssitia)

- The formal creation of the Agoge as state-controlled education

Classical period (c. 550-371 BCE):

The mature Agoge system operated during Sparta’s height of power, creating the warriors who became legendary throughout Greece.

Decline and modification (371 BCE onwards):

After devastating defeat at Leuctra (371 BCE) shattered Spartan invincibility, the Agoge evolved:

- Citizen numbers declined catastrophically (to perhaps 1,000-1,500)

- Non-Spartiates increasingly integrated into the system

- Training may have intensified or been modified

- The system continued in modified form even under Roman rule

The Agoge System: Age-by-Age Breakdown

The Agoge was a comprehensive life-stage system, controlling Spartan males from birth through age 30. Let’s examine each phase:

Birth to Age 7: Early Selection

Inspection of newborns:

Contrary to popular myth (largely from Plutarch), Spartans probably didn’t throw “defective” infants off cliffs. However, inspection of newborns did occur:

- Male infants brought before elders for examination

- Sickly or deformed infants might be denied citizenship rights or left exposed (exposure was common throughout Greece, not unique to Sparta)

- Only healthy infants accepted for eventual Agoge entry

Early childhood:

Boys lived with their families until age 7, though Spartan parenting emphasized toughness:

- Minimal coddling or affection (by ancient accounts)

- Physical hardening exercises

- Suppression of crying or complaint

- Early learning of Spartan values and expectations

The mothers’ role:

Spartan mothers were famously stern, supposedly telling sons to “come back with your shield or on it” (meaning victory or death—defeated soldiers abandoned heavy shields while fleeing; dead soldiers were carried home on their shields). Whether this specific phrase was common or literary invention, Spartan mothers certainly reinforced military values.

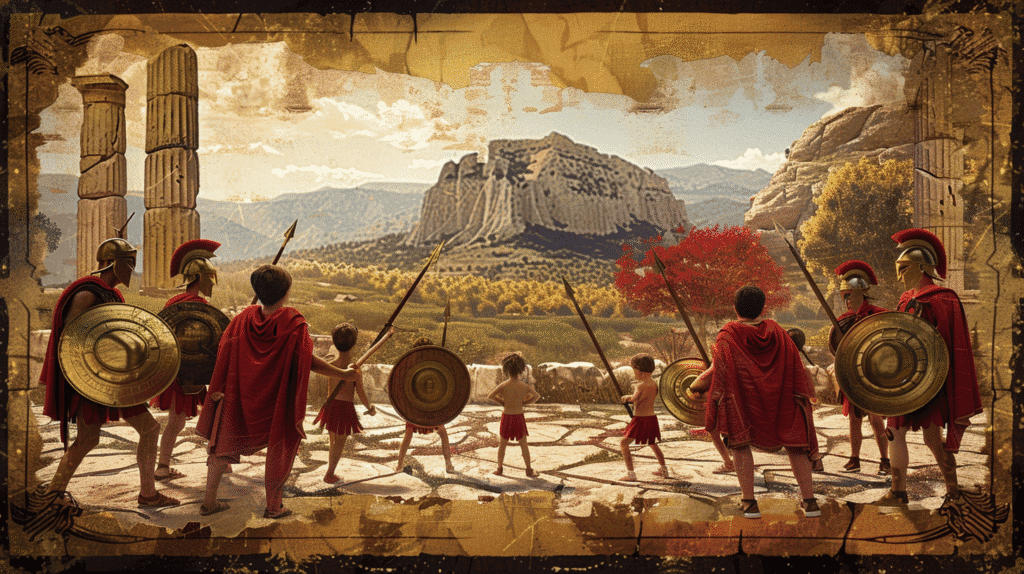

Ages 7-12: The Mikichizomenos (Little Boys)

The separation:

At age 7, boys entered the Agoge. This wasn’t gradual—they were taken from their families to live in communal barracks, seeing their parents only occasionally.

Organization and supervision:

Agelai (ἀγέλαι, “packs” or “herds”): Boys organized into age-cohort groups

Bouagos: The strongest, most promising boy in each group designated as leader, teaching early leadership and responsibility

Paidonomos (παιδονόμος): The state official overseeing the entire Agoge, wielding absolute authority and carrying a whip

Eirenes (εἴρενες): Older youths (ages 18-20) who directly supervised younger boys and administered discipline

Living conditions:

Barracks life: Boys slept in communal dormitories with minimal comfort

Bedding: Slept on rushes or reeds they had to gather themselves from riverbanks, forbidden to use knives (so they tore them by hand)

Clothing: Single cloak (τρίβων, tribōn) worn year-round, regardless of weather. Bathed infrequently. Went barefoot.

Diet: Deliberately insufficient rations, keeping boys perpetually hungry

Hair: Kept short initially, in contrast to the long hair they’d wear as adults

The education begins:

Physical training: Wrestling, running, gymnastics, swimming, javelin throwing

Literacy: Basic reading and writing (Spartans were literate, contrary to some myths), though minimal compared to other Greek states

Music and dance: Group singing and war dances (pyrrhic dances) to develop rhythm and coordination

Laconic speech: Training to speak briefly and sharply, without unnecessary words (giving us the word “laconic” from Lakonia, Sparta’s region)

Stealing as education:

One of the Agoge’s most notorious features was institutionalized theft:

The system: Boys given insufficient food, forced to steal to supplement rations

The lesson: Not about acquiring food (which the state could easily provide) but about:

- Cunning and stealth

- Risk assessment

- Self-reliance

- Courage under pressure

The punishment: Beaten severely if caught—not for stealing but for being caught, for failing at stealth

Historical example: Plutarch tells of a boy who stole a fox, hid it under his cloak, and let it gnaw his stomach to death rather than reveal the theft and face punishment. Whether true or apocryphal, this story illustrates the values being taught.

Ages 12-18: The Adolescent Phase

Training intensified as boys became teenagers:

Physical training escalation:

Increased exercise: More demanding physical conditioning, preparation for wearing 60+ pound hoplite armor

Combat training: Introduction to actual weapons—spear, sword, and especially the hoplon (heavy round shield)

Formation drill: Practice in phalanx formation, learning to move as coordinated unit

Endurance tests: Long-distance marching, carrying heavy loads, operating on minimal sleep

The brutal competition:

Diamastigosis (ritual whipping at Artemis Orthia’s altar):

Perhaps the Agoge’s most notorious practice:

- Boys whipped before an altar in an endurance contest

- Compete to see who could endure longest without crying out

- Spectators (including tourists in Roman period) watched

- Deaths occasionally occurred

- Proved courage, pain tolerance, and devotion to honor

Combat tournaments: Organized fights between boys, sometimes brutal, developing fighting skills and competitive spirit

The emphasis on pairs:

Boys often formed close bonds with specific partners:

- Training pairs practiced together

- Older youths mentored younger boys (some relationships became sexual, following Greek pederastic traditions)

- These bonds reinforced unit cohesion and mutual obligation

Educational elements:

Syssitia attendance: Began attending communal mess halls, learning adult behaviors and customs

Political observation: Allowed to listen to adult discussions, learning statecraft and decision-making

Cultural education: Continued music and poetry, especially martial poetry celebrating Spartan victories

Ages 18-20: The Eirenes (Youth)

This transitional period marked the shift from student to junior instructor:

Role reversal: Eirenes supervised younger boys, administering discipline and teaching skills they’d recently mastered

Krypteia (κρυπτεία, “secret service”):

The most controversial Agoge institution:

The practice: Select eirenes sent into countryside armed only with daggers, surviving by stealth, living rough, and—according to sources—assassinating helots

The purpose (debated by historians):

- Military training: Developing survival skills, stealth, and killing ability

- Terror tactics: Intimidating helot population through random killings

- Intelligence gathering: Scouting for potential revolt leaders

- Final test: Proving absolute loyalty by performing morally challenging acts

Historical evidence: Thucydides and Plutarch describe krypteia, though details are murky. Modern historians debate how routinely it involved murder versus surveillance and survival training.

Advanced military training:

- Tactical education in warfare strategies

- Leadership development

- Final preparation for service as hoplites

Ages 20-30: Full Warriors but Not Full Citizens

Military service: Became full hoplite soldiers, fighting in Sparta’s wars

The syssitia requirement: Must join a communal mess hall and contribute from their land allotments. Failure to contribute meant loss of citizenship—economic failure became social death.

Marriage: Could marry but couldn’t live with wives. Continued living in barracks, visiting wives secretly at night.

The continuation: Even after “graduating,” men remained under military discipline, attending training, participating in the syssitia, and maintaining constant readiness.

Full citizenship: Only at age 30 could men live with their families, though military obligations continued until age 60.

Daily Life in the Agoge: The Experience of Brutality

What was daily existence actually like for boys in the Agoge? Let’s examine typical experiences:

A Day in the Life

Dawn:

- Wake before sunrise to cold water washing (minimal hygiene)

- Brief breakfast (black broth or barley porridge—never enough)

- Morning assembly and inspection

Morning:

- Physical training: running, wrestling, gymnastics

- Combat drill: weapons practice, formation training

- Supervised by eirenes who correct errors with whips or fists

Midday:

- Minimal rest period

- Insufficient lunch ration

- Possible theft attempts to supplement food (if caught, beating follows)

Afternoon:

- Continued physical training or educational instruction

- Music, dance, or poetry recitation

- Sometimes combat competitions between boys

Evening:

- Evening meal (again insufficient)

- Attendance at syssitia for older boys, observing adult discussions

- Return to barracks

Night:

- Sleep on reed beds, single cloak for warmth

- Older boys might conduct night exercises or survival training

- Eirenes patrol, administering discipline for infractions

The Psychological Mechanisms

The Agoge’s effectiveness depended on sophisticated (if brutal) psychological techniques:

Deliberate hardship:

Purpose: Constant discomfort created mental toughness and suppressed concern for physical comfort

Method: Hunger, cold, inadequate rest, pain became normal, making battlefield conditions less shocking

Sleep deprivation: Limited sleep reduced resistance to authority and created psychological stress that built resilience

Fear and violence:

Arbitrary punishment: Rules enforced inconsistently and punitively, creating chronic anxiety and absolute obedience

Public humiliation: Errors punished publicly, creating intense shame and incentive to avoid failure

Pain tolerance training: Regular beatings and pain tests normalized violence and built pain endurance

Competition and hierarchy:

Constant ranking: Boys ranked against each other, competing for status and avoiding bottom positions

Peer pressure: Groups held collectively responsible for individual failures, creating intense social pressure to conform

Leadership rotation: Some boys given temporary authority over others, then returned to subordinate positions, teaching both leadership and obedience

Identity erasure:

Suppression of family ties: Separation from parents weakened family loyalty, redirecting allegiance to state and unit

Uniformity: Identical clothing, identical training, identical treatment created collective rather than individual identity

Emotional suppression: Crying, complaint, or affection actively punished, creating stoic, emotionally controlled personalities

The Stockholm Syndrome effect:

Modern psychology recognizes that victims of systematic abuse sometimes identify with their abusers. The Agoge may have produced similar effects:

- Boys internalized values of their tormentors

- Graduates defended and perpetuated the system

- Suffering became source of pride rather than trauma

The Female Experience: The Agoge for Girls

While less documented, Sparta’s education system for girls was unique in the ancient Greek world:

Physical Training for Girls

Unprecedented equality: Unlike other Greek states where girls were largely confined, Spartan girls received formal education

Athletic training:

- Running, wrestling, gymnastics

- Javelin and discus throwing

- Swimming and dancing

Public exercise: Controversially (to other Greeks), girls exercised outdoors, sometimes minimally clothed or nude, like boys

Purpose: Not for military service but for:

- Bearing healthy children (physical fitness improved maternal and infant health)

- Maintaining household during male military deployment

- Embodying Spartan ideals of strength and discipline

Education and Culture

Literacy: Girls learned reading, writing, and arithmetic—unusual for ancient Greece

Music and poetry: Participated in choruses and festivals

Civic values: Educated in Spartan history, values, and expected behaviors

Marriage preparation: Trained for role as Spartan wife and mother, including managing estates (since husbands were often absent)

The Spartan Mother Ideal

Spartan women gained reputation for toughness:

Famous sayings (possibly apocryphal but culturally significant):

- “Come back with your shield or on it”

- “Only Spartan women give birth to men”

- When asked why Spartan women alone ruled their men: “Because we alone give birth to men”

Property rights: Spartan women could own land and property—extraordinary for ancient Greece

Social power: With men constantly at war or in barracks, women managed significant aspects of Spartan society

The Products of the Agoge: What It Created

What kind of men emerged from this brutal system?

The Ideal Spartan Warrior

Physical capabilities:

- Exceptional strength and endurance

- High pain tolerance

- Proficient in weapons and formation fighting

- Capable of operating on minimal resources

Psychological traits:

- Absolute courage (allegedly—fear of dishonor exceeded fear of death)

- Unquestioning obedience to authority

- Emotional suppression and stoicism

- Fierce loyalty to unit and state

Social behaviors:

- Laconic speech (brief, pointed, witty)

- Disdain for luxury or comfort

- Collective identity over individualism

- Rigid adherence to customs and laws

Military Effectiveness

The phalanx perfected: Sparta’s warriors fought in the classic Greek phalanx formation:

- Dense formation of heavily armored hoplites

- Large round shields (hoplon) overlapping for mutual protection

- Long spears (dory) projecting forward

- Depth of 8-12 ranks, presenting wall of shields and spear points

Why Spartans excelled: The Agoge created advantages:

- Cohesion: Years of shared hardship created unbreakable unit bonds

- Discipline: Ability to maintain formation under extreme pressure

- Courage: Less likely to break and run than other Greek hoplites

- Training: Professional soldiers vs. citizen-farmers who trained occasionally

Battlefield reputation:

- Other Greeks feared facing Spartans

- Spartans rarely retreated or broke formation

- Famous for singing paeans (battle hymns) as they advanced

- Red cloaks reportedly worn so blood wouldn’t show, maintaining fearsome appearance when wounded

Historical examples:

Battle of Thermopylae (480 BCE): 300 Spartans (and 700 Thespians) held off Persian empire for three days, dying to the last man rather than retreat

Battle of Plataea (479 BCE): Spartan contingent critical to Greek victory over Persians

Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE): Spartan military superiority eventually defeated Athens despite Athenian naval and economic advantages

The Costs and Limitations

Demographic catastrophe:

The Agoge was so brutal many didn’t survive or succeed:

- High mortality during training

- Strict citizenship requirements meant failure = exclusion

- Birth rates among Spartiates remained low

- Population declined from ~10,000 to ~1,500 over two centuries

Intellectual stagnation:

Focus on military training suppressed other developments:

- Minimal philosophy, science, or arts compared to Athens

- Economic development restricted

- Technological innovation limited

- Cultural influence far less than militarily weaker Athens

Strategic inflexibility:

The system created excellent hoplites but:

- Struggled with new tactics (light infantry, cavalry, siege warfare)

- Couldn’t replace losses quickly (each soldier took 23 years to produce)

- Failed to adapt when warfare evolved

Psychological damage:

Though ancient sources don’t discuss it, modern psychology suggests the Agoge produced:

- Trauma and PTSD (though not recognized in ancient times)

- Emotional stunting and difficulty with normal relationships

- Possible sadistic tendencies from normalized violence

- Rigid thinking and inability to adapt to peace

The Decline and End of the Agoge

The system that made Sparta powerful ultimately contributed to its downfall:

The Crisis of Decreasing Numbers

The oliganthropia (“shortage of men”):

By the 4th century BCE, Spartan citizen numbers had collapsed:

- From ~10,000 Spartiates (c. 480 BCE) to ~1,500 (c. 371 BCE)

- By 250 BCE, perhaps only 700 remained

Causes:

- Strict citizenship requirements meant economic failure = loss of status

- Land consolidation concentrated wealth among few families

- War casualties couldn’t be replaced quickly

- Low birth rates among the elite

The vicious cycle: Fewer Spartans meant more vulnerable to helot revolt, requiring harsher control, requiring more warriors, but fewer available…

Military Defeat and Loss of Prestige

Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE):

Theban general Epaminondas shattered Spartan invincibility:

- Revolutionary tactics defeated the Spartan phalanx

- 400 of 700 Spartiates present were killed—a catastrophic loss

- Spartan military supremacy ended permanently

Consequences:

- Messenian helots liberated, eliminating Sparta’s economic base

- Spartan power collapsed across Greece

- The mystique of Spartan invincibility destroyed

Transformation and Continuity

Hellenistic period: Sparta became a minor power, attempting various reforms:

- Kings Agis IV and Cleomenes III tried to revive the Agoge and redistribute land

- Temporary successes followed by failures and executions

- The system continued in modified form

Roman period: Under Roman rule, the Agoge became a tourist attraction:

- Ritual whipping contests performed for Roman spectators

- The system more display than functional military training

- Sparta traded on its historical reputation

Final end: The Agoge finally disappeared sometime in the 3rd or 4th century CE as Sparta faded into obscurity.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Despite ending 1,700 years ago, the Agoge remains culturally significant:

Military Training Influence

Modern military academies draw (selectively) from Spartan principles:

Shared hardship: Boot camps use deliberate discomfort to build cohesion and resilience

Stress inoculation: Controlled stress exposure prepares soldiers for combat stress

Unit cohesion emphasis: Recognition that bonds between soldiers matter more than individual prowess

Leadership under pressure: Training future officers in decision-making under stress

Critical differences: Modern training avoids the Agoge’s:

- Child soldiers (modern forces recruit adults)

- Deliberate cruelty (beyond necessary hardship)

- Suppression of independent thought (modern militaries value initiative)

- Lifetime commitment from childhood

Cultural Impact

Popular culture: The Agoge features prominently in:

- Films (300, 300: Rise of an Empire)

- Literature (Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield)

- Video games (Assassin’s Creed Odyssey)

- Comics and graphic novels

Fitness and self-improvement: “Spartan” races and training programs exploit the brand, emphasizing toughness and endurance

Political rhetoric: The term “Spartan” evokes discipline, sacrifice, and martial virtue in political discourse

Cautionary Lessons

Modern analysis reveals troubling aspects:

Child abuse: By contemporary standards, the Agoge constituted systematic child abuse

Militarism’s costs: Sparta’s single-minded focus on military power led to cultural stagnation and eventual collapse

Sustainability issues: The system that created Sparta’s strength also contained seeds of its destruction

Human costs: Military effectiveness came at enormous human cost—trauma, broken families, demographic decline

The danger of total institutions: When state control becomes absolute, individual flourishing becomes impossible

Conclusion: The Paradox of Spartan Excellence

The Agoge created the ancient world’s most formidable warriors through a system we would now recognize as institutionalized child abuse. This paradox lies at the heart of Sparta’s legacy: extraordinary effectiveness achieved through methods we find morally reprehensible.

The boys who entered the Agoge at age seven experienced systematic hardship designed to break their individuality and remake them as perfect soldiers. Most modern observers would see trauma; Spartans saw education. We see cruelty; they saw necessary preparation for the violence of ancient warfare and the constant threat of helot rebellion.

The system worked, at least for a time. Spartan warriors were genuinely superior to other Greek hoplites—more disciplined, more cohesive, more willing to stand their ground. The phalanx of Spartan hoplites was the ancient world’s most feared military formation. The reputation alone often won battles before they began.

But the costs were staggering. Sparta produced military excellence while sacrificing everything else—arts, philosophy, economic development, and ultimately its own sustainability. The demographic catastrophe caused by the Agoge’s selectivity and brutality destroyed Spartan power more effectively than any enemy.

What can the Agoge teach us?

The power of systems: Institutions shape people profoundly. The Agoge demonstrates how comprehensive systems can fundamentally alter human behavior and psychology.

The price of specialization: Sparta’s exclusive focus on military excellence came at the cost of everything else—a warning about the dangers of monomaniacal focus.

Cohesion through shared hardship: The Agoge validates (in extreme form) the principle that shared adversity creates powerful social bonds—used in modern military training but without the Agoge’s cruelty.

The limits of discipline: Discipline and toughness have value, but the Agoge shows they can’t compensate for declining numbers, strategic inflexibility, and failure to adapt.

Child development matters: Modern psychology reveals that childhood trauma has lifelong consequences. The Agoge’s effectiveness doesn’t justify its methods by contemporary ethical standards.

Sustainability requires balance: Systems that push humans to extremes may achieve short-term results but prove unsustainable. Sparta’s collapse illustrates this principle.

The Agoge stands as a fascinating historical experiment—a society that pushed human training to absolute extremes and, for a time, succeeded in its goals. But it also stands as a warning: the creation of perfect soldiers came at the cost of creating a viable society. Military excellence alone couldn’t save Sparta when citizen numbers collapsed and the helots were freed.

When we look at the Agoge today, we see both achievement and tragedy—the capacity of human systems to shape extraordinary capability, and the terrible costs of pursuing single-minded excellence at the expense of all else. The Spartan warriors were real, their courage genuine, their discipline remarkable. But they were created through a process we can study, understand, even learn from—while recognizing that some historical achievements came at prices we should never be willing to pay again.