Table of Contents

Joan of Arc: The Warrior Saint Who Led the French Army in the 15th Century

Introduction: The Peasant Girl Who Changed History

Joan of Arc, known as the Maid of Orléans, stands as one of the most remarkable figures in world history. A peasant girl who became a military commander, she defied every convention of medieval society to lead the French army against English occupation during the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453).

What makes Joan’s story so extraordinary is not just her military victories, but the circumstances under which she achieved them. At an age when most teenagers today are completing high school, this illiterate farm girl commanded thousands of soldiers, broke a siege that military experts thought impossible to lift, and orchestrated the coronation of a king. Claiming divine guidance through mystical visions, she inspired a demoralized nation to believe in itself again.

Despite her eventual capture, trial, and execution at just nineteen years old, Joan of Arc became a symbol of courage, faith, and national identity that transcends time and borders. Her legacy continues to inspire discussions about leadership, faith, gender roles, and resistance against overwhelming odds.

This comprehensive guide explores Joan of Arc’s extraordinary life, from her humble beginnings to her military triumphs, her tragic death, and her enduring influence on France and the world.

Understanding the Historical Context: France on the Brink of Collapse

The Hundred Years’ War Crisis

To truly appreciate Joan of Arc’s impact, we must first understand the desperate situation facing France in the early 15th century. The Hundred Years’ War had been devastating the kingdom for nearly a century, but by the 1420s, France faced potential extinction as an independent nation.

The conflict began in 1337 as a succession dispute. English kings claimed the French throne through family connections, while the French nobility supported their own candidates. What started as a dynastic quarrel evolved into a brutal war that would reshape both nations.

By the time Joan was born in 1412, France was fractured and facing collapse:

Military disasters had shattered French confidence. The catastrophic defeats at Crécy (1346) and Agincourt (1415) demonstrated the superiority of English longbowmen over French knights, destroying the myth of invincible French chivalry.

Political division weakened resistance. France was split between supporters of the Dauphin Charles (later Charles VII) and the Burgundians, powerful French nobles who allied with England. This civil war within the larger conflict meant Frenchmen were fighting Frenchmen while the English expanded their control.

Territorial losses were staggering. By 1429, England controlled most of northern France, including Paris. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) had even declared that the English king would inherit the French throne, effectively disinheriting Charles VII.

Economic devastation spread everywhere. Constant warfare destroyed crops, depopulated villages, and disrupted trade. Bands of unemployed soldiers turned to banditry, terrorizing the countryside.

Psychological despair gripped the nation. Many French people believed their cause was lost, that God had abandoned them, and that English rule was inevitable.

Into this darkness stepped an unlikely savior: a teenage girl from a remote village who claimed angels had commanded her to save France.

The Rise of Joan of Arc: From Obscurity to National Figure

A Humble Beginning with a Divine Mission

Joan of Arc was born around January 6, 1412, in Domrémy, a small village in northeastern France near the border with Burgundian territory. Her parents, Jacques d’Arc and Isabelle Romée, were peasant farmers of modest means but respectable standing in their community. Joan grew up performing typical rural tasks—tending livestock, spinning wool, and helping with farmwork—receiving no formal education and remaining illiterate throughout her life.

Despite her unremarkable circumstances, Joan’s childhood was shaped by the war raging across France. Domrémy itself suffered raids from Burgundian forces, and the young girl witnessed firsthand the devastation war brought to ordinary people. Her village’s loyalty to the Dauphin Charles meant they lived under constant threat from pro-English forces.

The visions that would change history began when Joan was approximately thirteen years old. She later described hearing voices accompanied by brilliant light while in her father’s garden. She identified these voices as belonging to Saint Michael the Archangel, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, and Saint Margaret of Antioch—all revered figures in medieval Christian tradition.

These divine messengers, Joan claimed, gave her a seemingly impossible mission: she must travel to the Dauphin Charles, help him reclaim his kingdom, and ensure his coronation at Reims Cathedral. The voices told her that she would lead French forces to victory and drive the English from France.

For a teenage peasant girl in medieval society, this mission was absurd on every level. Women didn’t lead armies. Peasants didn’t advise kings. Illiterate villagers didn’t develop military strategy. Yet Joan’s faith in her divine calling was absolute and unshakeable.

The Journey to Convince a Skeptical Court

Joan’s path to the French court was far from straightforward. Her first attempts to gain an audience with the Dauphin were met with ridicule and dismissal. In 1428, at age sixteen, she approached Robert de Baudricourt, the garrison commander at Vaucouleurs, asking for an armed escort to meet Charles VII. Baudricourt initially laughed at her request and sent her away.

Undeterred, Joan returned to Vaucouleurs several months later. This time, her persistence and conviction began to win supporters. Local residents, impressed by her piety and certainty, began to believe she might truly be divinely inspired. Baudricourt, hearing reports of her growing reputation and perhaps influenced by France’s desperate situation, finally agreed to provide her with an escort.

The journey to Chinon, where Charles held court, was dangerous. Joan and her small escort had to travel through enemy-controlled territory, riding at night to avoid detection. She cut her hair short and wore men’s clothing for practicality and safety—a decision that would later be used against her at her trial.

Gaining the Trust of the French Court

In March 1429, Joan of Arc arrived at the royal fortress of Chinon, where the Dauphin Charles held his diminished court. The challenge before her was immense: convince a skeptical, war-weary prince that a teenage peasant girl had been sent by God to save his kingdom.

Charles VII himself was in a precarious position. Not yet officially crowned, he faced questions about his legitimacy. Rumors circulated that he might be illegitimate, which undermined his claim to the throne. English propaganda portrayed him as a pretender, and his own mother had disowned him in favor of the English king. He was financially struggling, militarily weak, and surrounded by advisors who disagreed on strategy.

When Joan finally gained an audience, legend holds that Charles disguised himself among his courtiers to test her. According to these accounts, Joan walked directly to the disguised Dauphin and identified him without hesitation, then revealed to him a private prayer he had made to God—something only he knew. While historians debate the accuracy of this dramatic story, something about Joan’s demeanor and message clearly impressed the beleaguered prince.

Charles ordered a formal examination of Joan before entrusting her with any military role. A commission of theologians and church officials in Poitiers questioned her extensively about her visions, her mission, and her faith. They examined her character, looking for signs of heresy, witchcraft, or deception. Additionally, a group of noble ladies confirmed her virginity—important for establishing her purity and reinforcing her claim to be the “Maid” chosen by God.

After weeks of investigation, the commission declared Joan to be of sound faith and good character, finding no evidence of evil influence. This official endorsement gave Charles the religious and political cover he needed to accept her help.

Joan was provided with armor, a horse, weapons, and a personal standard (banner) bearing the images of Jesus and angels. Significantly, Joan chose to carry this banner rather than a sword into battle, emphasizing her role as a spiritual leader rather than a killer. She later testified that she preferred her banner “forty times better” than a sword and never killed anyone in battle.

Her presence immediately energized French forces. Soldiers who had lost hope in their cause suddenly believed victory was possible. Joan’s unwavering confidence, her claim to divine backing, and her genuine concern for her troops created a powerful psychological transformation. She insisted on moral discipline in the army—forbidding looting, expelling prostitutes from the camps, and requiring soldiers to confess their sins before battle.

Within weeks of arriving at court, this unknown village girl had become the most talked-about figure in France, preparing to lead an army to break one of the most important sieges of the war.

Joan of Arc’s Greatest Military Victories

The Siege of Orléans (1429): The Battle That Changed Everything

The Siege of Orléans stands as Joan of Arc’s most famous victory and one of the most significant turning points in the Hundred Years’ War. To understand its importance, we must recognize what was at stake: if Orléans fell, the path would be open for English forces to conquer southern France, potentially ending French independence forever.

Why Orléans Mattered

Orléans occupied a strategic position on the Loire River, serving as the gateway to southern France. It was one of the last major cities loyal to Charles VII that stood between the English-controlled north and the as-yet-unconquered south. The city’s location made it essential for trade, communication, and military movements.

The English siege began in October 1428, with forces commanded by the Earl of Salisbury (later replaced after his death by the Earl of Suffolk and Lord Talbot). The English built a ring of fortified positions (bastilles) around the city, cutting off supply lines and bombarding the defenses. However, they lacked sufficient troops to completely encircle Orléans, leaving some gaps in their siege lines.

By early 1429, the situation inside Orléans was becoming desperate. Supplies were running low, morale was collapsing, and the defenders expected the city to eventually fall. French attempts to relieve the siege had failed, and military experts saw no realistic way to break the English stranglehold.

Joan’s Arrival Transforms the Situation

Joan of Arc arrived at Orléans on April 29, 1429, accompanied by a relief force and supply convoy. Her arrival had an immediate psychological impact that cannot be overstated. Word of the virgin warrior sent by God had spread throughout France, and the exhausted defenders suddenly had hope.

The military commander Jean de Dunois (the “Bastard of Orléans”) initially had reservations about following the advice of a seventeen-year-old girl with no military training. However, he quickly recognized her unique ability to inspire troops. Joan’s presence transformed demoralized soldiers into confident warriors willing to take risks they had previously avoided.

Joan immediately advocated for an aggressive strategy. Rather than waiting passively for the siege to tighten, she urged French forces to attack the English fortifications directly. Her confidence was infectious, and even veteran commanders found themselves caught up in her certainty that God would grant them victory.

The Assault: Nine Days That Saved France

Beginning on May 4, 1429, Joan led a series of coordinated attacks against the English bastilles surrounding Orléans:

Day 1 (May 4): The Fort of Saint-Loup The first assault targeted the fortress of Saint-Loup, east of the city. Joan personally led the attack, carrying her banner and urging soldiers forward. Despite fierce English resistance, the French overwhelmed the position after several hours of combat. This victory provided a crucial boost to French morale while demonstrating that the English fortifications could be taken.

Day 2 (May 5): Rest and Preparation Joan urged immediate follow-up attacks, but military commanders insisted on a day of rest. Joan used this time to pray and prepare the troops spiritually, hearing confessions and leading religious ceremonies.

Day 3 (May 6): The Island Fortresses French forces attacked English positions on an island in the Loire River, capturing the fort of Saint-Jean-le-Blanc and then the Augustins monastery fortress. These victories cleared the southern approach to the city.

Day 4 (May 7): The Decisive Battle at Les Tourelles The assault on Les Tourelles, the most heavily fortified English position guarding the bridge into Orléans, would prove decisive. This fortress was considered nearly impregnable, defended by hundreds of English soldiers and protected by the river.

Joan personally led the attack, climbing a siege ladder while holding her banner. During the fierce fighting, a crossbow bolt struck her between her neck and shoulder, penetrating several inches. Her soldiers, seeing her fall, began to panic and retreat.

But Joan refused to quit. After having the arrow removed—a painful process she bore without complaint—she rested briefly, then returned to the battlefield. Her reappearance stunned both French and English forces. Seeing their divinely inspired leader back in the fight, French soldiers rallied with renewed determination.

The battle raged for hours, but by evening, the French achieved a breakthrough. Les Tourelles fell, and the English forces began a general retreat from their siege positions.

Day 5 (May 8): The English Withdrawal On the morning of May 8, the remaining English forces outside Orléans formed a battle line, expecting a final confrontation. Joan and her army marched out to face them but did not immediately attack. The two armies faced each other for about an hour. Then, remarkably, the English withdrew, abandoning the siege after seven months.

The Siege of Orléans was broken, and France had its first major victory in years.

The Impact of Victory at Orléans

The psychological, military, and political consequences of Orléans were enormous:

It shattered the myth of English invincibility. For the first time in decades, French forces had won a decisive, clear-cut victory against their enemy.

It validated Joan’s divine mission in the eyes of the French people. Her claim to be sent by God seemed confirmed by miraculous success.

It transformed military morale across France. Cities and towns that had been neutral or resigned to English rule began to support Charles VII.

It proved that aggressive tactics could overcome English defensive advantages. The traditional French approach of attacking well-positioned English longbowmen had led to disasters like Agincourt. Joan’s faith-driven assaults, combined with smart tactical choices, showed a new way forward.

It made Charles VII’s coronation possible. With Orléans secure, the path to Reims—where French kings were traditionally crowned—was now viable.

Joan of Arc had arrived at Orléans as an unknown peasant girl with a divine mission. She left as the savior of France and one of the most famous people in Europe.

The Loire Valley Campaign: Momentum Builds

Following the liberation of Orléans, Joan urged an immediate campaign to drive English forces from the Loire Valley and clear a path to Reims. Charles VII and his advisors, still cautious despite the recent victory, were reluctant to commit to such an ambitious plan. But Joan’s growing influence and the army’s confidence in her leadership eventually overcame their hesitation.

In June 1429, Joan led French forces in a rapid campaign to recapture English-held towns along the Loire River:

Jargeau (June 12, 1429): The French assaulted this fortified town despite being outnumbered by the English garrison. Joan was struck on the head by a stone during the fighting but continued to lead the assault. The town fell after intense combat, and the English commander, the Earl of Suffolk, was captured.

Meung-sur-Loire (June 15, 1429): French forces captured the bridge at this strategic location, though the English garrison held the town itself. Control of the bridge was the key objective, allowing French forces to move freely in the region.

Beaugency (June 16-17, 1429): This English-held town surrendered after a brief siege when the garrison learned that a large French army was approaching. The English forces withdrew under terms of safe conduct.

The Battle of Patay (June 18, 1429): This engagement would prove to be one of the most decisive victories of the entire war.

The Battle of Patay: Reversing Agincourt

The Battle of Patay is often called the “reverse Agincourt” because it demonstrated how completely the momentum of the war had shifted. English forces under Sir John Fastolf and Lord Talbot, retreating from the Loire Valley, were caught by pursuing French cavalry before they could establish their traditional defensive position.

At battles like Agincourt and Crécy, English longbowmen had devastated French cavalry charges by establishing strong defensive positions with sharpened stakes protecting them. The longbow’s range and rate of fire could destroy attacking forces before they closed to combat distance. This tactical advantage had given England seemingly impossible victories for decades.

At Patay, however, the French caught the English vanguard before their archers could deploy properly. French cavalry, led by commanders inspired by Joan’s recent successes, charged with unprecedented aggression. The English forces, caught in the open, were overwhelmed in less than an hour.

The results were devastating for the English: perhaps 2,000-2,500 English soldiers killed compared to minimal French losses. Important English commanders including Lord Talbot were captured. The psychological impact was immense—it proved that English forces could be not just defeated but utterly destroyed in open battle.

While Joan was present at Patay, her exact tactical role is unclear. However, her influence on French morale and aggressive tactics was undeniable. The commanders who won at Patay did so with a confidence and boldness that Joan had inspired.

The Coronation of Charles VII at Reims

With the Loire Valley secured and the English reeling from defeats, Joan pressed Charles VII to march to Reims for his coronation. This journey would require traveling deep into territory that was officially under Burgundian and English control—a risky proposition even after recent victories.

Charles’s advisors were divided. Some argued that consolidating their gains and building strength made more strategic sense than a dangerous march north. Others worried that Joan’s influence over the king was becoming too great. But Joan was insistent: the coronation was essential to Charles’s legitimacy, and God had commanded her to see it done.

The March to Reims: A Triumphal Progress

In late June 1429, Charles VII and Joan set out with an army of approximately 12,000 soldiers, heading north toward Reims. What could have been a harrowing campaign through hostile territory became instead a remarkable demonstration of how completely Joan’s victories had changed the political landscape.

Town after town opened its gates without resistance. Auxerre, Troyes, Châlons-en-Champagne—all welcomed Charles rather than face the divinely inspired French army. Joan’s reputation preceded her. Stories of the miraculous virgin warrior sent by God spread faster than the army itself, convincing garrisons and townspeople that resistance was futile.

At Troyes, there was brief hesitation, as the city was strongly held by Burgundian forces. When the Burgundian garrison refused to surrender, Joan prepared for an assault, personally directing the placement of artillery and the construction of siege works. Her determination and the memory of Orléans convinced the defenders to negotiate. After tense discussions, Troyes surrendered peacefully.

By mid-July, the French army reached Reims, and the city welcomed Charles enthusiastically.

The Coronation Ceremony (July 17, 1429)

On July 17, 1429, in the magnificent Gothic splendor of Reims Cathedral, Charles VII was crowned King of France in the traditional ceremony that dated back centuries. The coronation followed ancient rituals, including anointing with holy oil said to have been brought from heaven for the baptism of Clovis, the first Christian king of the Franks, in 496 CE.

Joan of Arc stood beside the new king during the ceremony, holding her banner. When asked later why her banner had such a place of honor, Joan replied simply: “It had borne the burden, it was right that it should share the honor.”

This moment represented the fulfillment of Joan’s divine mission as she understood it. The voices that had spoken to her in Domrémy had commanded her to see Charles crowned at Reims, and she had accomplished exactly that. In just three months, she had transformed France’s prospects from near-hopeless to triumphant.

The Significance of the Coronation

The coronation at Reims carried profound implications:

It established Charles VII’s legitimacy beyond question. In medieval political theory, a king wasn’t truly a king until anointed and crowned. The English had prevented Charles’s coronation specifically to undermine his authority. Now that he had been properly crowned at the traditional site with the traditional ceremony, his claim to the French throne became spiritually and politically unassailable.

It invalidated the Treaty of Troyes. This 1420 treaty had declared that the English king would inherit France. With Charles properly crowned, the treaty’s legitimacy collapsed.

It rallied wavering nobles and towns to the French cause. Many who had remained neutral or supported the English out of pragmatism now recognized that France’s fortunes had turned. Declaring for Charles became the safe political choice.

It elevated Joan’s status to something approaching sainthood in the popular imagination. She had predicted these events, and they had come to pass exactly as she said. To ordinary French people, this was clear proof of divine intervention.

Yet Joan herself seemed to understand that her unique moment was passing. She had accomplished the specific mission given to her by her voices. What came next would be more complicated.

The Decline: From Triumph to Tragedy

The Failed Assault on Paris and Shifting Politics

After the triumphant coronation at Reims, Joan of Arc believed the war should continue immediately. To her, the logical next step was clear: march on Paris, the largest city in France and the seat of English power. She argued passionately that French momentum should be exploited before the English could regroup.

However, the atmosphere at the French court had changed. Charles VII, now securely crowned, became more receptive to his traditional noble advisors, who were less enthusiastic about Joan’s continued influence. Several factors contributed to growing resistance to Joan’s leadership:

Political jealousy among nobles and military commanders who resented taking orders from or sharing glory with a peasant girl. Joan’s unprecedented rise threatened established hierarchies and wounded the pride of aristocrats.

Financial and logistical exhaustion from the rapid campaigns. Charles’s treasury was depleted, and maintaining a large army in the field was expensive.

Diplomatic considerations regarding the Duke of Burgundy. Charles’s advisors hoped to negotiate a peace settlement with Burgundy, separating them from the English alliance. Aggressive military campaigns might undermine these diplomatic efforts.

Skepticism about Joan’s continued divine favor. Some at court wondered if Joan’s mission had been fulfilled with the coronation. Perhaps God’s plan was now complete, and continuing to follow a teenage girl’s visions was risky.

Despite these reservations, Charles authorized an assault on Paris, though with less than wholehearted support.

The Battle of Paris (September 8, 1429)

On September 8, 1429, Joan led an attack against Paris’s formidable defenses. The city’s walls were strong, manned by a large garrison of English and Burgundian troops, and the population—influenced by Burgundian propaganda—was hostile to Charles VII.

Joan personally led the assault, advancing to the walls and calling for the city’s surrender. When her appeals were rejected with insults and arrows, she directed the attack on the Saint-Honoré gate. French forces attempted to fill the defensive moat with bundles of wood while under heavy fire from defenders on the walls.

During the assault, Joan was struck by a crossbow bolt that pierced her thigh. Despite the painful wound, she refused to retreat, continuing to direct the attack from the front lines. Her courage inspired her troops, who fought fiercely to breach the walls.

However, the assault ultimately failed. The Parisian defenses were too strong, the garrison too large, and French forces—without Charles’s full commitment—lacked sufficient numbers and equipment for a successful siege. More critically, Charles VII ordered a withdrawal the following day, halting the campaign before Joan could organize another attempt.

The failure at Paris marked a turning point in Joan’s career. It was her first major setback, and it signaled that her influence with Charles was waning. Over the following months, Joan found herself increasingly sidelined at court, consulted less frequently, and her advice often overruled by nobles and advisors who had never trusted her.

Minor Campaigns and Growing Frustration

Through late 1429 and early 1430, Joan participated in various small-scale military operations, but without the resources or support she had enjoyed during the Orléans campaign. Charles VII’s court became absorbed in diplomatic negotiations with Burgundy, pursuing a political settlement rather than military victory.

Joan grew increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and defensive strategy. She believed God had sent her to drive the English from France completely, not to settle for a negotiated compromise. Her voices, she claimed, continued to urge action, but the French court was no longer listening.

This period highlights an important aspect of Joan’s character: she was not politically sophisticated. Her understanding of her mission was straightforward and absolute—God had commanded her to save France, and she would obey regardless of political calculations. The complex diplomacy and compromise necessary for running a kingdom were foreign to her direct, faith-driven approach.

In spring 1430, Joan learned that the town of Compiègne, a French stronghold north of Paris, was under attack by Burgundian forces. Without waiting for royal authorization, Joan gathered troops and rushed to Compiègne’s defense. This independent action would prove to be her last military campaign.

Capture at Compiègne (May 23, 1430)

On May 23, 1430, Joan led a sortie from Compiègne against the besieging Burgundian forces. It was a characteristically bold move—attacking a larger enemy force to relieve pressure on the town’s defenders.

The attack initially caught the Burgundians off guard, but reinforcements arrived quickly, and the French raiders found themselves outnumbered. Joan, commanding the rear guard, covered the retreat of her soldiers back toward Compiègne’s gates.

What happened next remains controversial among historians. As French forces retreated into the city, the gates were closed while Joan and a small group of soldiers were still outside, fighting desperately against surrounding Burgundian troops. Whether the gates were closed deliberately to abandon Joan or closed in the confusion of battle is debated, but the result was the same: Joan was trapped outside the walls.

Accounts of her capture describe her fighting furiously, refusing multiple demands to surrender, until she was finally pulled from her horse by Burgundian soldiers. The Maid of Orléans, who had never been defeated in battle, was now a prisoner of her enemies.

Abandoned by the King She Crowned

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of Joan’s capture was what followed: Charles VII made no serious effort to ransom or rescue her.

In medieval warfare, ransoming captured nobles and important prisoners was standard practice. Joan had made Charles VII king, saved his kingdom, and stood beside him at his coronation. Yet when she fell into enemy hands, Charles abandoned her to her fate.

Why Charles failed to help Joan is a matter of historical speculation:

Political calculations may have led Charles and his advisors to conclude that Joan had outlived her usefulness. With the king crowned and French fortunes stabilized, the peasant visionary who had never fit comfortably into the royal court might have become an embarrassment.

Financial constraints were real—Charles’s treasury was not wealthy, and ransoms could be expensive. However, given Joan’s importance, this explanation seems insufficient.

Diplomatic concerns about negotiations with Burgundy might have made Charles reluctant to antagonize the Burgundians by insisting on Joan’s release.

Belief that Joan’s mission was complete may have convinced Charles and his advisors that Joan’s capture was part of God’s plan, and therefore should not be interfered with.

Whatever the reasons, the fact remains: Charles VII did nothing while his greatest supporter was sold to his enemies and put on trial for her life. This betrayal adds a bitter note to Joan’s story and raises uncomfortable questions about gratitude, loyalty, and political expediency.

The Trial and Execution of Joan of Arc

A Politically Motivated Prosecution

After her capture by Burgundian forces in May 1430, Joan of Arc was held prisoner for several months while negotiations took place regarding her fate. The English, desperate to reverse their military losses and discredit the woman who had become a symbol of French resistance, were determined to obtain custody of Joan.

In November 1430, the Burgundians sold Joan to the English for 10,000 livres tournois—a substantial sum equivalent to a king’s ransom. The transaction revealed the political nature of her imprisonment: she was not treated as a prisoner of war, which would have entitled her to certain protections under medieval customs, but as a political criminal.

The English wanted to destroy Joan’s reputation and, by extension, delegitimize Charles VII’s kingship. If they could prove that Joan was a heretic, a witch, or a fraud, they could argue that Charles VII had been crowned by someone in league with the devil, thus invalidating his authority.

However, the English couldn’t simply execute Joan as a prisoner of war—that would make her a martyr and possibly strengthen French resolve. Instead, they arranged for her to be tried by an ecclesiastical court on charges of heresy. If the Church declared her a heretic, her execution would appear to be a religious necessity rather than political murder.

The Rigged Trial at Rouen

Joan was transferred to Rouen, the English-occupied capital of Normandy, where she would face trial. The proceedings were overseen by Pierre Cauchon, the Bishop of Beauvais, a pro-English cleric who had fled his diocese when it fell to French forces. Cauchon had strong political and financial motivations to please the English, who paid him handsomely for his services.

The trial began in January 1431 and was fundamentally unjust from the start:

Joan was denied legal counsel, despite requests for someone to help her navigate the complex theological questions she faced.

She was imprisoned in an English military fortress rather than in Church custody, as was customary for ecclesiastical prisoners. This meant she was guarded by English soldiers, who subjected her to harassment and threats. She was kept in chains and had to sleep in a cell with male guards—a situation that placed her in constant danger.

The court was composed entirely of pro-English clergy, many of whom were financially dependent on English patronage. Several clerics who tried to speak in Joan’s defense were threatened or expelled from the proceedings.

The interrogations were designed to trap her. Joan was questioned repeatedly, often for hours at a time, with judges attempting to trick her into contradicting herself or saying something heretical.

The Charges: Heresy, Witchcraft, and Cross-Dressing

Joan faced multiple charges, but they essentially fell into three categories:

1. Claiming Direct Communication with God

The most serious charge was that Joan claimed to receive direct revelation from God through her visions of Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret. The court argued that she should have submitted her visions to the Church for approval rather than acting on them independently.

This charge was theologically sophisticated and dangerous. Medieval Catholic theology held that divine revelation had ended with the apostles, and that the Church hierarchy—not individual believers—had the authority to interpret God’s will. By claiming direct divine guidance that led her to act without Church approval, Joan was potentially guilty of heresy.

Joan defended herself brilliantly during these interrogations. When asked if she was in God’s grace (a trick question—answering “yes” suggested sinful pride, while answering “no” suggested she knew she was damned), she replied: “If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me.”

2. Witchcraft and Sorcery

The court insinuated that Joan’s military victories and her ability to inspire loyalty were the result of witchcraft rather than divine favor. They questioned her about a ring she wore, a banner she carried, and even about a tree in Domrémy where villagers held festivals, suggesting these were instruments of magic.

These charges were largely propaganda, designed to frighten superstitious people and provide an alternative explanation for her remarkable successes. The court never proved any actual practice of witchcraft, but the accusation alone was damaging.

3. Cross-Dressing

Joan was charged with violating divine law by wearing male clothing—specifically armor and men’s tunics. This charge might seem trivial to modern readers, but it was taken very seriously in medieval theology, as it referenced biblical prohibitions in Deuteronomy 22:5 against men wearing women’s clothing or vice versa.

Joan had practical reasons for wearing male clothing. During her military campaigns, armor was essential for protection, and male clothing was more suitable for riding horses and military life. In prison, she reportedly wore men’s clothing for protection against sexual assault by her guards.

However, the court insisted that wearing male clothing was a sign of rejecting her God-given nature as a woman, and thus heretical. This charge would ultimately prove crucial to her execution.

Joan’s Defense: Courage Under Impossible Circumstances

Despite having no legal training and being only nineteen years old, Joan demonstrated remarkable intelligence, courage, and wit during her trial. The transcripts of her interrogations reveal a young woman who refused to be intimidated by dozens of educated clerics working to trap her.

Some notable exchanges include:

When asked if she knew she was in God’s grace, her careful answer (quoted above) impressed even her judges, who recognized they couldn’t trap her on that question.

When asked if Saint Michael appeared to her naked, she replied: “Do you think God cannot afford to clothe him?”

When pressed about whether her voices spoke French or English, she answered sarcastically: “Why would they speak English when they are not on the English side?”

When asked to submit to the Church’s judgment, she replied that she would submit to God and the Church triumphant (meaning the Church in heaven), but she could not deny her visions to please the “Church militant” (the earthly Church institution), especially when that institution was clearly serving English political interests.

Her responses demonstrate both her sharp mind and her absolute faith in her divine mission. She would not deny her voices, even to save her life, because to do so would be to deny God himself.

The Verdict and Execution

After months of interrogation, the court threatened Joan with torture if she did not confess. They took her to a chamber where instruments of torture were displayed and demonstrated, attempting to break her will. Joan refused to recant.

Finally, on May 24, 1431, the court took Joan to a cemetery in Rouen where a large crowd had gathered and a pyre had been prepared. Under threat of immediate execution, Joan signed or marked a document (she was illiterate) that appeared to recant her claims and submit to Church authority. In exchange, her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

However, within days, Joan was again wearing male clothing. Whether this was because her female clothing had been stolen by guards (as she later claimed) or because she chose to return to male dress is disputed. Regardless, when the court learned she had “relapsed” into her heresy, they had the legal justification they needed.

Joan was declared a relapsed heretic—someone who had confessed and then returned to their heretical ways. Under medieval Church law, relapsed heretics could be “relaxed” to secular authorities for execution. The sentence was carried out immediately.

May 30, 1431: Burned at the Stake

On the morning of May 30, 1431, nineteen-year-old Joan of Arc was led to the old marketplace in Rouen, where a large crowd had gathered. She was tied to a tall wooden stake atop a pyre of wood and straw.

Witnesses reported that Joan maintained her courage and faith to the end. She asked for a crucifix, and an English soldier made a small cross from two sticks and gave it to her. She held this cross to her chest. A priest also held up a larger crucifix so she could see it through the flames.

As the fire was lit, Joan’s final words were reportedly: “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus!” She called on God’s name as the smoke and flames engulfed her. According to some accounts, the English executioner built the fire particularly high so that the crowd couldn’t hear what Joan said, fearing her words might inspire the gathered French citizens.

After Joan died, the English ordered her body burned twice more to ensure nothing remained. Her ashes were then gathered and thrown into the Seine River, ensuring that there would be no relics for her supporters to venerate. The English wanted to erase her memory completely.

They failed utterly. Instead of destroying Joan’s legacy, her execution transformed her into a martyr whose memory would inspire France for centuries.

The Legacy of Joan of Arc: From Martyr to Saint

Immediate Aftermath: A Rallying Cry for France

The execution of Joan of Arc did not have the effect the English intended. Rather than discrediting her and demoralizing French resistance, her death outraged many in France and strengthened resolve against English occupation.

Joan became a martyr for the French cause. Stories spread of her courage at the trial, her unwavering faith, and her final words calling on Jesus. People began to view her not as a heretic but as a holy woman murdered by English enemies.

The momentum she had created continued. French forces, inspired by her memory, kept up the offensive. By 1435, just four years after Joan’s death, Burgundy switched sides and allied with France. Paris fell to French forces in 1436. By 1453, the English had been driven from all of France except Calais, effectively ending the Hundred Years’ War.

Charles VII, who had abandoned Joan to her fate, nevertheless benefited enormously from her legacy. He ruled France until 1461, presiding over a recovery and centralization of royal power that Joan had made possible.

The Rehabilitation Trial (1456): Declaring Joan Innocent

By the 1450s, with France secure and victorious, Charles VII had both political and personal motivations to clear Joan’s name. Having been crowned by someone the Church had declared a heretic was problematic for his legitimacy. Additionally, Joan’s mother, Isabelle Romée, and her brothers petitioned the Church to review the case.

In 1455, Pope Calixtus III authorized a new investigation into Joan’s original trial. A panel of theologians, bishops, and legal scholars conducted an extensive review, interviewing witnesses who had known Joan and examining the proceedings at Rouen.

The findings were unequivocal:

The 1431 trial was fraudulent, conducted by biased judges with political motivations.

The charges against Joan were unjust, and she had been denied proper legal protections and rights.

Joan’s actions and beliefs were consistent with Catholic teaching, and her visions were not heretical.

On July 7, 1456, the rehabilitation trial declared Joan innocent of all charges. The verdict of the 1431 trial was overturned, and Joan was recognized as a faithful Catholic who had been wrongly executed. While she was not immediately declared a saint, this official recognition of her innocence was the first step toward her eventual canonization.

The Path to Sainthood (1456-1920)

Joan’s recognition as a saint did not come quickly. The Catholic Church’s canonization process is deliberately lengthy and thorough, requiring investigation of the candidate’s life, verification of miracles attributed to their intercession, and extensive theological review.

Interest in Joan’s canonization grew during the 19th century, partly driven by Napoleon Bonaparte, who promoted Joan as a symbol of French nationalism. The Church began a formal investigation in 1869.

The process moved slowly, but steadily:

1909: Pope Pius X beatified Joan, declaring her “Blessed Joan of Arc” and recognizing her heroic virtue.

1920: Pope Benedict XV canonized Joan, declaring her Saint Joan of Arc and recognizing her as a patron saint of France.

Joan was also declared the patron saint of soldiers and of prisoners. Her feast day is May 30, the anniversary of her martyrdom.

Why Joan’s Story Endures: Timeless Themes

Joan of Arc’s story continues to resonate because it touches on fundamental human experiences and questions:

Faith Versus Authority

Joan’s trial centered on a question that remains relevant: when does an individual’s conscience override institutional authority? Joan believed God had spoken directly to her, and she refused to deny this experience even when Church officials demanded she do so. This conflict between personal conviction and institutional power appears throughout history in religious reformations, political revolutions, and civil rights movements.

The Power of Belief

Joan’s military victories were partly tactical, but largely psychological. Her absolute faith in her divine mission inspired soldiers to believe they could win. This demonstrates how belief—whether we interpret it as religious faith, psychological confidence, or collective morale—can influence real-world outcomes.

Gender and Power

In medieval society, women were excluded from warfare, politics, and Church leadership. Joan violated all these boundaries, commanding armies, advising kings, and claiming direct divine revelation. Her story raises questions about gender roles, social expectations, and whether exceptional circumstances can justify breaking societal rules. Different eras have interpreted Joan through their own cultural lenses regarding gender—medieval Catholics saw a holy virgin, 19th-century feminists saw a proto-feminist warrior, modern historians see a complex historical figure whose gender identity might be more nuanced than traditional accounts suggest.

Youth and Leadership

Joan was a teenager—just seventeen when she arrived at Charles VII’s court, nineteen when she died. Her story demonstrates that age doesn’t necessarily determine wisdom, courage, or capability. This resonates particularly with young people who feel their voices aren’t taken seriously by older generations.

Class and Opportunity

Joan rose from illiterate peasant to military commander and national hero. Her story appeals to democratic and meritocratic ideals—the notion that greatness can emerge from anywhere, regardless of birth or education.

Martyrdom and Justice

Joan’s unjust trial and execution raise eternal questions about justice, political persecution, and how history judges those who were wrongly condemned in their time. Many historical figures who were persecuted—from Socrates to Martin Luther King Jr.—share this pattern of being vindicated by later generations.

Joan in Art, Literature, and Popular Culture

Few historical figures have inspired as much creative work as Joan of Arc. Her story has been retold countless times, in virtually every medium:

Literature

William Shakespeare portrayed Joan (as “Joan la Pucelle”) in Henry VI, Part 1 (1591), though his portrayal was hostile, reflecting English prejudices of his era.

Mark Twain wrote Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (1896), which he considered his finest work despite its being his least popular. Twain’s Joan is portrayed as genuinely heroic and divinely inspired.

George Bernard Shaw’s play Saint Joan (1923) presents a complex Joan whose visions might be divine inspiration or psychological conviction—Shaw leaves the question open.

Countless other novels, poems, and plays continue to be written about Joan, each interpreting her through the lens of its era.

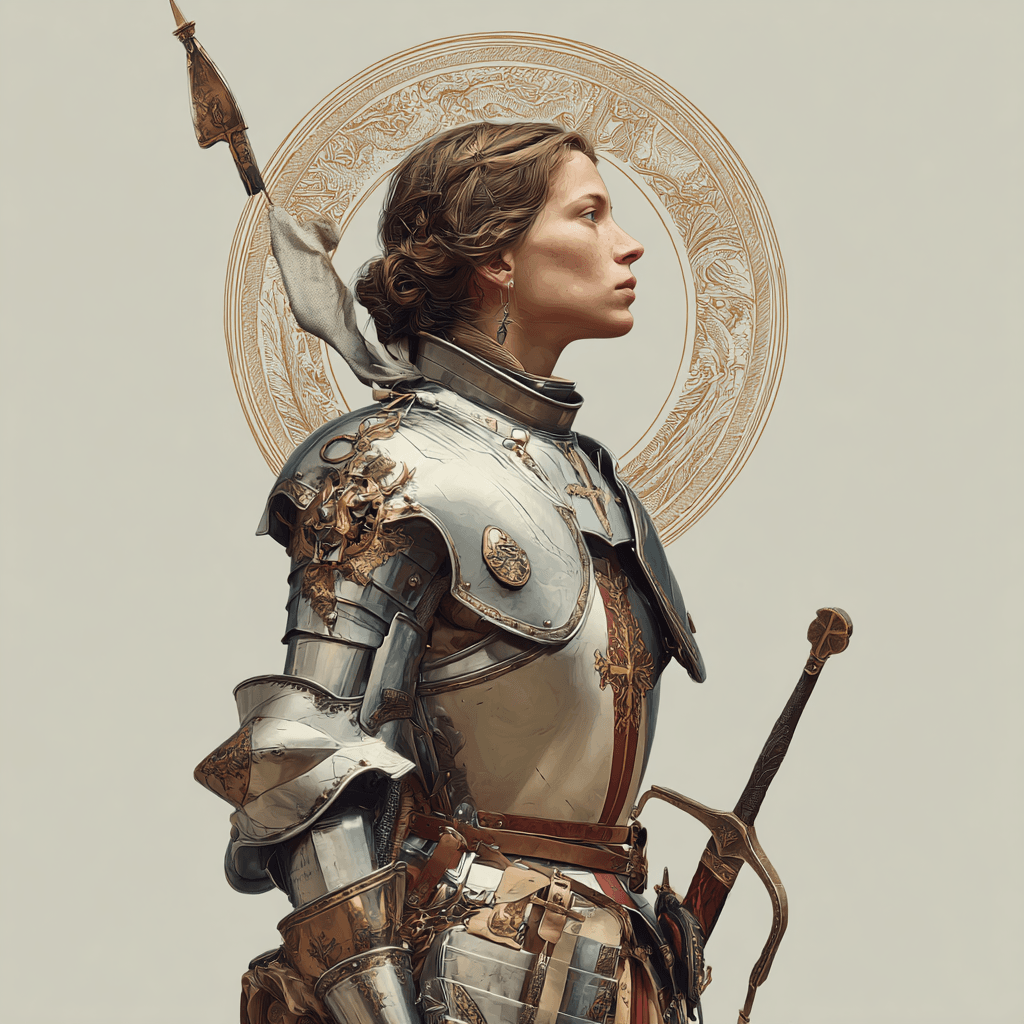

Visual Art

Joan has been portrayed by virtually every major French artist from the 15th century onward. Notable works include:

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII (1854) shows Joan in gleaming armor, representing 19th-century Romantic nationalism

- Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc (1879) depicts her receiving her visions in her family garden

- Countless statues and monuments to Joan exist throughout France, with major ones in Paris, Orléans, and Rouen

Film and Television

Joan’s story translates well to visual media, with dozens of film and TV portrayals:

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) is considered one of the greatest silent films ever made, focusing intensely on Joan’s trial and execution through extreme close-ups of actress Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s face.

Luc Besson’s The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999), starring Milla Jovovich, presents a more action-oriented and psychologically complex Joan.

Numerous other films and TV series continue to be produced, each offering different interpretations—some emphasize her military leadership, others her spiritual visions, still others her tragic martyrdom.

Music and Opera

Joan has inspired numerous musical works:

Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Giovanna d’Arco (1845) Arthur Honegger’s oratorio Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher (1938) Leonard Cohen’s song “Joan of Arc” (1971) Countless other musical works in classical, popular, and folk traditions

Video Games

Modern video games have introduced Joan’s story to new generations:

Age of Empires II (1999) features a campaign following Joan’s military victories Multiple other strategy and role-playing games include Joan as a character or reference her story

Joan as Symbol: Claimed by Many Causes

Joan’s story is malleable enough that various groups have claimed her as a symbol for their causes:

French nationalists have long invoked Joan as the embodiment of French identity and resistance to foreign domination. During World War I and World War II, Joan’s image appeared on posters encouraging French soldiers and citizens to resist German occupation.

Catholic Church celebrates her as a saint who remained faithful to God despite persecution by a corrupt ecclesiastical court.

Feminists have seen Joan as an early example of a woman breaking gender barriers and proving women’s capability in traditionally male domains.

Military organizations honor her as a patron saint of soldiers and an example of courageous leadership.

Various political movements across the ideological spectrum have claimed Joan—from monarchists to republicans, from conservatives to progressives—each emphasizing different aspects of her story.

LGBTQ+ communities have recently explored whether Joan’s cross-dressing and rejection of traditional feminine roles might indicate a gender identity more complex than historical accounts acknowledged, though this interpretation remains speculative and controversial.

This universal appeal is both Joan’s strength and weakness as a historical figure. She means so many things to so many people that her actual historical self sometimes gets lost beneath layers of interpretation and appropriation.

Modern Scholarship on Joan of Arc

Contemporary historians continue to study Joan, applying new methodologies and asking new questions:

Psychological analyses explore what Joan’s visions might have been—genuine mystical experiences, epileptic seizures, schizophrenia, religious fervor, or something else entirely.

Military historians examine her actual tactical contributions, noting that while she was an inspirational leader, experienced commanders like Jean de Dunois handled much of the actual strategy.

Gender studies scholars analyze how Joan navigated medieval gender roles and what her story reveals about women’s agency in medieval society.

Religious historians investigate medieval mysticism and how Joan’s claims fit into the broader context of medieval religious experience, when mystical visions were more commonly reported and accepted.

Political historians examine how Joan’s story influenced concepts of nationalism, divine right of kings, and popular sovereignty.

The ongoing scholarly interest in Joan ensures that new insights into her life and legacy continue to emerge.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Joan of Arc’s Story

Joan of Arc lived for only nineteen years, and her military career lasted less than two years. Yet in that brief time, she changed the course of European history.

She arrived when France seemed doomed to disappear as an independent nation, conquered by England and torn apart by civil war. Through her leadership, she inspired a demoralized nation to believe in itself again. Her military victories at Orléans, Patay, and throughout the Loire Valley reversed the tide of the Hundred Years’ War. Her determination secured Charles VII’s coronation, establishing his legitimacy and unifying French forces.

Her tragic death transformed her into something greater than any military victory could have achieved—a martyr whose story would inspire centuries of resistance against injustice and oppression.

What makes Joan’s story eternally relevant is its fundamental humanity. She was an ordinary person thrust into extraordinary circumstances, who refused to be limited by the expectations society placed on her. She heard what she believed was God’s voice, and she obeyed, regardless of the personal cost. She demonstrated courage, faith, and determination that defied all reasonable expectations.

Whether we interpret her visions as divine revelation, psychological conviction, or something in between, the result was the same: a teenage peasant girl became a military commander, a kingmaker, and ultimately a saint. Her story reminds us that greatness can emerge from anywhere, that conviction can move armies, and that a single individual with sufficient courage can change the world.

Joan of Arc remains a symbol that transcends time, place, and ideology—a reminder that faith, courage, and determination can overcome seemingly impossible obstacles. Her legacy lives on not just in France, but wherever people face overwhelming odds and refuse to surrender.

For anyone seeking inspiration to stand up for their beliefs, to challenge injustice, or to believe that they can make a difference despite their limitations, Joan of Arc’s story offers a powerful message: even the most unlikely person, armed with conviction and courage, can change history.

Additional Resources

For those interested in learning more about Joan of Arc and the Hundred Years’ War, these resources provide deeper insight:

- The National Museum of the Middle Ages in Paris houses medieval artifacts and provides context for understanding Joan’s era

- Biography.com’s Joan of Arc profile offers an accessible overview of her life and legacy