Table of Contents

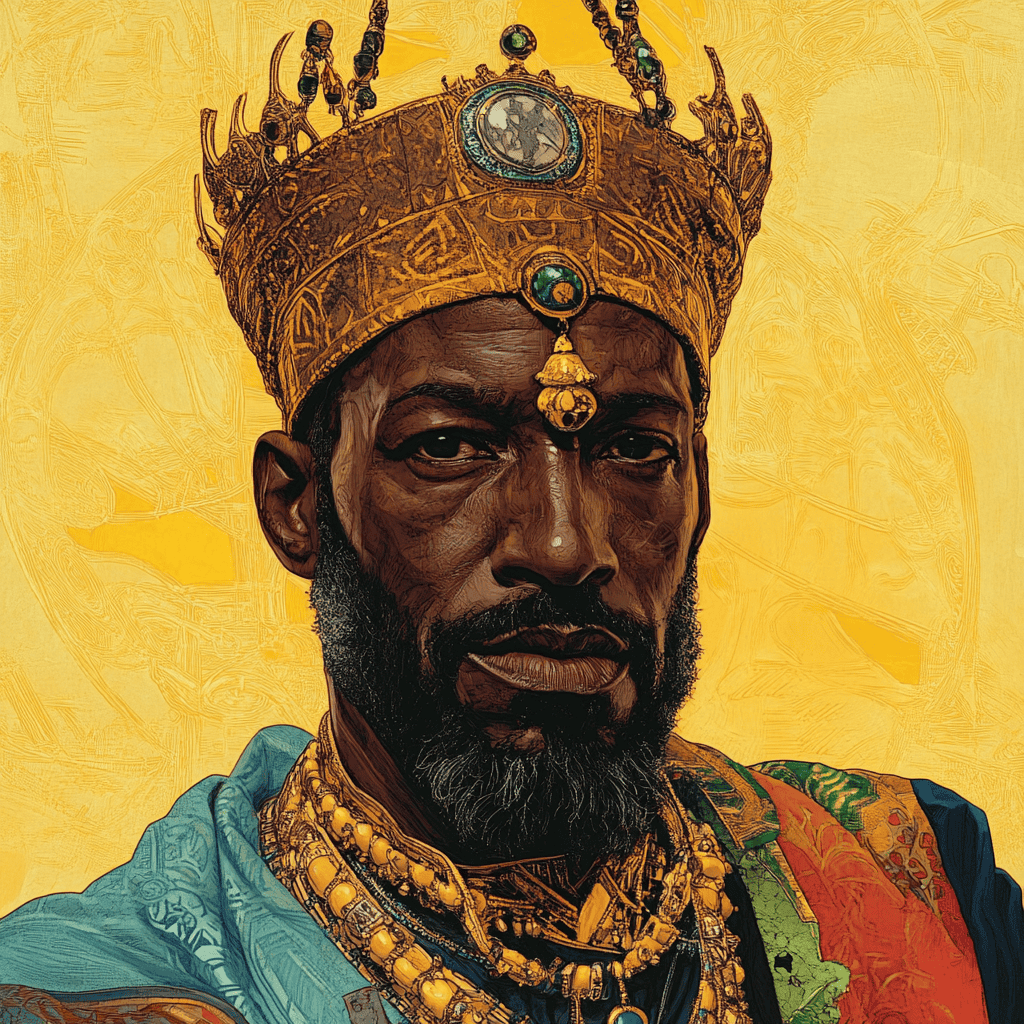

Mansa Musa: The Warrior King Who Elevated the Mali Empire in the 14th Century

Introduction: The Richest Man in History

Mansa Musa, the tenth ruler of the Mali Empire (r. 1312–1337 CE), stands as one of the most fascinating figures in world history. While he’s often remembered simply as “the richest man who ever lived,” this characterization, though likely accurate, barely scratches the surface of his remarkable reign and lasting influence.

His wealth was almost incomprehensible by any standard. Modern economists attempting to calculate his net worth have suggested figures ranging from $400 billion to over $600 billion in today’s currency—though some argue his wealth was so vast as to be essentially incalculable. At the height of his power, Mansa Musa controlled nearly half of the world’s gold supply, making his empire’s economy larger than many European kingdoms combined.

But Mansa Musa was far more than a wealthy monarch sitting atop vast gold reserves. He was a military strategist who expanded Mali’s territory to unprecedented size, a cultural patron who transformed Timbuktu into one of the world’s great centers of learning, and a diplomatic genius whose legendary pilgrimage to Mecca fundamentally altered how the Islamic world and medieval Europe viewed Africa.

His reign represented the apex of West African civilization during the medieval period, proving that Africa was home to sophisticated empires that rivaled anything in Europe or Asia. The Mali Empire under Mansa Musa controlled territory larger than Western Europe, maintained trade networks spanning three continents, and supported universities and libraries that preserved and advanced human knowledge.

This comprehensive exploration examines Mansa Musa’s rise to power, his military campaigns and conquests, his unprecedented economic influence, his cultural and educational legacy, and his enduring impact on African and world history. His story challenges outdated narratives about African history while revealing the complexity and grandeur of medieval West African civilization.

Understanding the Historical Context: West Africa Before Mansa Musa

The Geography of Wealth: Gold, Salt, and the Trans-Saharan Trade

To understand Mansa Musa’s extraordinary wealth and power, we must first understand the economic and geographic context of medieval West Africa—a region that was, in many ways, the economic engine of the medieval world.

West Africa possessed something the medieval world desperately wanted: gold. While Europe suffered from chronic gold shortages that limited their economies, West Africa had abundant gold deposits in regions like Bambuk, Bure, and Galam. This gold flowed north across the Sahara Desert to North Africa, the Middle East, and eventually Europe, making the trans-Saharan trade routes some of the most valuable commercial pathways in the world.

The trans-Saharan trade was based on a remarkable exchange:

Gold moved north from the gold-producing regions of West Africa, carried by massive camel caravans across the harsh Sahara Desert.

Salt moved south from Saharan salt mines like Taghaza, where massive salt slabs were mined and transported southward. In gold-rich but salt-poor West Africa, salt was literally worth its weight in gold—essential for preserving food, maintaining health, and supporting livestock.

Other goods also crossed the desert: enslaved people (tragically), ivory, leather, textiles, kola nuts, and exotic goods moved in both directions, creating a complex commercial network.

The key to wealth and power in this region was controlling the trade routes and the cities where goods were exchanged. The empire that could dominate this trade and tax the merchants passing through could accumulate unimaginable riches.

The Mali Empire’s Foundation: Sundiata Keita

The Mali Empire that Mansa Musa would inherit and expand was founded in the 13th century by Sundiata Keita, a figure of epic proportions in West African history whose story blends historical fact with legendary elements.

Sundiata’s story, preserved in the oral tradition of griots (West African storytellers and historians), tells of:

A crippled prince who overcame disability to become a great warrior

His defeat of the tyrannical sorcerer-king Sumanguru Kanté at the Battle of Kirina (c. 1235)

His establishment of the Mali Empire, unifying various Mandinka kingdoms under his rule

His creation of governmental structures and the Kouroukan Fouga (sometimes called the Mande Charter), an oral constitution that established principles of governance

By the time of Sundiata’s death, Mali controlled:

The gold-producing regions of Bambuk and Bure

Important trading cities along the Niger River

Agricultural lands that could support a large population

Strategic positions along the trans-Saharan trade routes

The Keita dynasty that Sundiata founded would continue to rule Mali for centuries, with each successive mansa (king) building on the foundation he established. This was the empire Mansa Musa would inherit—already wealthy and powerful, but not yet at its greatest extent or peak influence.

The State of Mali in 1312

When Mansa Musa came to power in 1312, the Mali Empire was already a significant regional power, but it faced both opportunities and challenges:

Strengths:

Control of major gold-producing regions

Established trade relationships with North African merchants

A functioning governmental system inherited from Sundiata

Military forces capable of defending Mali’s territory

Growing Islamic influence that connected Mali to the wider Muslim world

Challenges:

Neighboring kingdoms and cities (particularly Gao and the Songhai people) maintained independence

Not all trade routes were under Mali’s direct control

The empire’s eastern and northern borders remained vulnerable to raids

Mali’s wealth and reputation had not yet reached their legendary status

Mali was known in the Islamic world but remained relatively obscure to European traders and rulers

Into this context stepped Mansa Musa, who would transform Mali from a significant regional power into one of the great empires of the medieval world, rivaling the wealth and sophistication of any contemporary civilization.

The Rise of Mansa Musa: From Prince to Emperor

The Mysterious Expedition of Abu Bakr II

Mansa Musa’s path to the throne is one of history’s most intriguing stories, involving the mysterious disappearance of his predecessor and questions about what lies beyond the Atlantic Ocean.

Abu Bakr II (also known as Abubakari II), Mansa Musa’s predecessor, was apparently obsessed with a question that would not be definitively answered for another 170 years: What lay across the Atlantic Ocean?

According to accounts recorded by Arab historians, particularly Al-Umari (who interviewed people in Cairo who had met Mansa Musa), Abu Bakr II was consumed by the desire to explore the Atlantic. He organized not one but two major expeditions:

The First Expedition:

Abu Bakr II reportedly commissioned a fleet of 200 boats—some carrying sailors and supplies, others carrying trade goods and provisions.

These vessels set out into the Atlantic, with only one ship eventually returning.

The captain of that returning ship reported that the fleet had encountered a powerful current or whirlpool from which escape was impossible, and all other ships had been swept away.

The Second Expedition:

Undeterred by this catastrophic failure, Abu Bakr II organized an even larger expedition—reportedly 2,000 boats, including 1,000 carrying passengers and 1,000 carrying supplies.

This time, Abu Bakr II abdicated his throne to his deputy, Mansa Musa, and personally led the expedition.

Neither Abu Bakr II nor any of his fleet ever returned.

Historical Interpretation:

Some historians are skeptical of this account, suggesting it may be legendary or symbolic rather than literal. The numbers seem impossibly large, and no archaeological or historical evidence from the Americas corroborates contact with West African explorers in this period.

Others suggest there may be a core of truth—West African sailors and shipbuilders were sophisticated, and the Atlantic currents could carry vessels across the ocean (as Thor Heyerdahl’s Ra expeditions in the 1970s would demonstrate with reed boats). However, surviving such a crossing without navigational tools or knowledge of the distances involved would have been extraordinarily difficult.

The symbolic interpretation suggests that Abu Bakr II’s story might represent the dangers of hubris—a king who abandoned his responsibilities for personal glory, leaving his kingdom to a more sensible successor.

Regardless of the literal truth, this remarkable story set the stage for Mansa Musa’s ascension to power.

Mansa Musa’s Coronation (1312)

In 1312, with Abu Bakr II vanished and presumed dead, Mansa Musa ascended to the throne of the Mali Empire. While specific details of his coronation ceremony have not survived in historical records, we can infer some aspects from what we know about West African royal traditions and Islamic influences:

Traditional African ceremonies likely included:

- Recognition by the royal council and important nobles

- Ritual enthronement and symbolic gifts representing his authority

- Acknowledgment by griots who recited his genealogy connecting him to Sundiata Keita

- Military displays demonstrating his control over Mali’s armed forces

Islamic elements probably featured prominently, given Mali’s increasing Islamization:

- Prayers and blessings from Muslim religious leaders (imams)

- Possible oaths taken on the Quran

- Recognition from the ulama (Islamic scholars)

Mansa Musa inherited an empire that stretched across modern-day Mali, Senegal, southern Mauritania, Guinea, and parts of Niger—already one of the larger states in the medieval world. But he had ambitions to expand it further and to increase its prestige and influence beyond anything his predecessors had achieved.

Early Reign: Consolidating Power

The first years of Mansa Musa’s reign focused on consolidating his authority and strengthening the empire’s administrative and military systems. While specific details of these early years are sparse in the historical record, we can identify several key priorities:

Securing the loyalty of regional governors and local rulers who owed allegiance to the mansa but exercised considerable autonomy in their regions

Strengthening the military to defend Mali’s vast territory and prepare for future conquests

Developing administrative systems to efficiently collect taxes and tribute from throughout the empire

Building relationships with Islamic scholars and merchants, recognizing that Mali’s prosperity depended on maintaining strong connections to the trans-Saharan trade networks

Planning for expansion, identifying which neighboring territories should be brought under Mali’s control

These years of careful preparation would set the stage for the military conquests and cultural achievements that would define Mansa Musa’s legendary reign.

Mansa Musa’s Military Power and Conquests

The Mali Army: Organization and Strength

Mansa Musa commanded one of the largest and most effective military forces in the medieval world, estimated at approximately 100,000 soldiers—a staggering number for the 14th century that rivaled or exceeded the armies of contemporary European kingdoms and Islamic caliphates.

The composition and organization of this formidable force included:

Cavalry: The Elite Strike Force

Heavy cavalry formed the core of Mali’s offensive power:

- Warriors mounted on horses, often armored with quilted cotton armor that could deflect arrows and sword strikes

- Armed with long spears, swords, and javelins

- Capable of devastating charges that could break enemy formations

- Particularly effective in the relatively open terrain of the Sahel region

Light cavalry served crucial reconnaissance and harassment roles:

- More lightly equipped for speed and maneuverability

- Used bows and arrows to harass enemies from a distance

- Conducted scouting missions and pursued retreating enemies

- Essential for controlling the vast distances of Mali’s territory

The importance of cavalry in West African warfare cannot be overstated. Horses were expensive and difficult to maintain in tropical climates due to disease (particularly sleeping sickness carried by tsetse flies), which meant that only wealthy empires could field large cavalry forces. Mali’s control of trade routes allowed them to import horses from North Africa and maintain them in the drier Sahel regions, giving them a significant military advantage.

Infantry: The Foundation of Mali’s Armies

Spearmen and swordsmen provided the bulk of Mali’s military forces:

- Armed with iron-tipped spears, swords, and shields

- Often wore quilted cotton armor or leather protection

- Formed disciplined formations capable of withstanding cavalry charges and conducting assaults

Archers supplied crucial ranged firepower:

- Used powerful composite bows capable of penetrating armor at moderate ranges

- Could harass enemies before infantry closed for melee combat

- Essential for defending fortified positions and cities

The quality of Mali’s infantry was enhanced by iron weapons forged by skilled West African blacksmiths, whose ironworking technology was sophisticated and produced high-quality steel for weapons and tools.

Command Structure and Organization

The mansa served as supreme military commander, though he delegated tactical command to experienced generals during campaigns.

Regional commanders (farbas) governed provinces and commanded local military forces, providing both civil administration and military leadership.

The army was organized hierarchically with clear chains of command, ensuring discipline and effective coordination during campaigns.

Warriors were motivated by a combination of loyalty to the mansa, desire for glory and advancement, and material rewards including captured goods, land grants, and elevated social status.

The Conquest of Gao (1325): Strategic Expansion

One of Mansa Musa’s most significant military achievements was the conquest of Gao, a powerful city-state located on the Niger River approximately 400 kilometers east of Timbuktu. This campaign exemplified his strategic thinking and his ability to project military power across vast distances.

Why Gao Mattered

Gao was far more than just another city—it was a critical strategic and economic prize:

Strategic location: Positioned on the Niger River at a crucial crossing point, Gao controlled river traffic and trade routes extending east toward the Lake Chad region and north into the Sahara.

Commercial importance: As a major trading hub, Gao connected trans-Saharan caravan routes with riverine commerce, making it extremely wealthy from taxation and commercial activity.

Political significance: Gao was the center of Songhai power, representing an independent kingdom with its own military forces, cultural identity, and political ambitions. The Songhai people had a long history and would eventually build their own empire after Mali’s decline.

Prestige value: Conquering Gao demonstrated Mali’s military reach and deterred other potential rivals from challenging Mali’s dominance.

The Military Campaign

While specific tactical details of the campaign have not survived in historical records, we can reconstruct the general outlines:

Mansa Musa personally led or directed the campaign, demonstrating that this was a priority conquest rather than a minor border skirmish.

Mali’s forces likely numbered in the tens of thousands, representing a major military commitment.

The campaign probably involved both riverine and overland elements, with some forces moving by boat along the Niger River while others marched overland with cavalry support.

Gao’s defenses were overcome through a combination of military pressure, possible siege tactics, and perhaps negotiations that convinced some elements within Gao that resistance was futile.

The ruling family of Gao, including the dia (king) and his sons, were captured and brought to Mali’s capital as hostages. This was a common practice in medieval African warfare—keeping important hostages ensured the conquered population’s good behavior and prevented rebellion.

Integration of Gao into Mali’s Empire

Rather than destroying Gao or imposing harsh terms, Mansa Musa adopted a sophisticated approach to integration:

Local governance structures were largely preserved, with Mali appointing a farba (governor) to oversee the city while allowing local leaders to continue administering daily affairs.

Tribute and taxation were imposed, with Gao required to send regular payments of gold, goods, and military support to Mali.

Trade continued and even expanded under Mali’s protection, as merchants benefited from the security and stability that Mali’s military power provided.

Cultural exchange was encouraged, with Islamic scholars and merchants moving between Gao and other Mali cities like Timbuktu and Djenne.

The conquest of Gao extended Mali’s control several hundred kilometers eastward, securing the entire middle Niger River region and dramatically increasing Mali’s economic and strategic power.

Securing the Trans-Saharan Trade Routes

Beyond specific conquests like Gao, Mansa Musa’s military strategy focused heavily on securing and protecting the extensive trade routes that were the lifeblood of Mali’s economy.

The challenge was immense: The trans-Saharan trade routes stretched thousands of kilometers across some of the world’s harshest terrain, from the gold-producing regions of West Africa northward through the Sahara Desert to trading cities in North Africa like Sijilmasa, Cairo, and Tunis.

The Threat of Raiders and Bandits

Tuareg raiders posed a constant threat to caravan traffic:

- The Tuareg, nomadic Berber peoples of the Sahara, had intimate knowledge of desert conditions and could strike quickly against caravans

- They sought not just trade goods but also to capture people they could sell into slavery

- Their mobility and desert expertise made them formidable opponents

Other bandit groups also threatened commerce:

- Desperate people displaced by drought or conflict sometimes turned to raiding caravans

- Rogue military forces or mercenaries might prey on traders

- Political rivals of Mali might sponsor raids to disrupt commerce

Mali’s Military Response

Mansa Musa implemented a comprehensive security system:

Garrison towns along trade routes housed permanent military forces that could respond to threats:

- These garrisons were strategically placed at oases and key locations

- They provided resting points for caravans and military bases for punitive expeditions

- The weisuo system (military farming colonies) similar to China’s allowed soldiers to be self-sufficient while providing security

Cavalry patrols regularly swept the trade routes:

- Mobile forces could pursue raiders and prevent attacks

- Their presence deterred potential bandits who knew Mali’s reach was extensive

- These patrols also gathered intelligence about potential threats

Diplomatic efforts complemented military action:

- Mali negotiated agreements with Tuareg tribes, paying some to act as guides and protectors rather than raiders

- Traditional enemies were sometimes incorporated into Mali’s military system, turning former threats into assets

- Treaties and alliances extended Mali’s influence without constant military campaigns

Severe punishment for those who attacked Mali’s commerce:

- Captured raiders faced harsh penalties, serving as deterrents

- Entire groups that sponsored raids could face military retaliation

- Mali’s reputation for swift and effective response discouraged attacks

The results were dramatic: Under Mansa Musa’s protection, trans-Saharan trade flourished as never before. Merchants knew that traveling through Mali’s territory was relatively safe, which encouraged more trade, which generated more wealth, which allowed Mali to maintain even stronger security—a virtuous cycle that made Mali the dominant power in the region.

Expansion Beyond Gao: Growing the Empire

While the conquest of Gao was Mansa Musa’s most famous military achievement, his reign saw Mali’s territory expand in multiple directions:

Eastern expansion brought additional Songhai territories under Mali’s control, extending the empire’s reach toward the Lake Chad region.

Northern influence extended deeper into the Sahara, with Mali exercising varying degrees of control or influence over Saharan trading centers and oases.

Southern expansion incorporated additional gold-producing regions and agricultural lands, increasing both Mali’s wealth and its population.

Western consolidation strengthened Mali’s control over territories in modern Senegal and Guinea, securing the empire’s western flank.

By the end of Mansa Musa’s reign, the Mali Empire controlled approximately 1.29 million square kilometers (about 500,000 square miles)—roughly the size of Western Europe or slightly smaller than Alaska. This made Mali one of the largest empires in the world at that time, comparable in size to contemporary powers like the Delhi Sultanate or the Ilkhanate.

Military Organization and Innovation

Mansa Musa’s military success wasn’t just about numbers—it reflected sophisticated organizational and strategic thinking:

Logistics and supply systems allowed Mali to project power across vast distances:

- Organized supply depots along military routes

- Pre-positioned food, water, and equipment for campaigns

- Careful planning of movements to account for seasonal variations in water availability and temperature

Intelligence gathering provided information about enemies and potential threats:

- Merchants and travelers were debriefed about conditions in distant regions

- Spies and informants operated in rival kingdoms

- The extensive trade networks Mali controlled also served as information networks

Combined arms tactics integrated cavalry, infantry, and archers effectively:

- Cavalry charges broke enemy formations

- Infantry exploited breakthroughs and held positions

- Archers provided supporting fire and harassment

Fortification and defensive engineering protected key cities:

- Timbuktu, Gao, Djenne, and other important cities were fortified with walls

- Strategic locations had defensive works to control movement

- Mali’s military engineers understood siege warfare and defense

Flexible military organization allowed Mali to fight both conventional wars against organized kingdoms and counter-insurgency operations against raiders and rebels.

This sophisticated military system, combined with Mali’s economic strength that could sustain military operations, made Mansa Musa’s empire virtually unassailable during his reign.

The Legendary Pilgrimage to Mecca (1324-1325)

Planning the Greatest Journey in Medieval History

In 1324, Mansa Musa embarked on the religious obligation of hajj—the pilgrimage to Mecca that all Muslims who are able must attempt to complete at least once in their lives. However, Mansa Musa’s hajj would be unlike any pilgrimage before or since, becoming one of the most famous journeys in medieval history and fundamentally altering how the world viewed West Africa.

The journey from Mali to Mecca and back covered approximately 6,000-7,000 kilometers (roughly 4,000 miles) across some of the world’s most challenging terrain—the Sahara Desert, the Nile Valley, the Arabian Desert, and back. This was a journey that would take over a year to complete.

But Mansa Musa didn’t travel alone or lightly. He organized a caravan that was, by all accounts, one of the largest and most lavish processions the medieval world had ever seen.

The Magnificent Caravan: A Display of Imperial Power

Historical sources, particularly Arab chroniclers who witnessed or heard firsthand accounts of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage, provide detailed descriptions of this extraordinary procession:

The scale was breathtaking:

60,000 people accompanied Mansa Musa, according to contemporary accounts. This included:

- Soldiers and guards to protect the caravan and demonstrate Mali’s military might

- Royal officials and administrators who helped manage the journey and conduct diplomacy

- Islamic scholars and religious leaders who would study in Cairo and Mecca

- Merchants who would conduct trade along the route

- Griots (traditional oral historians and musicians) to document the journey and entertain

- Servants, cooks, and support staff to maintain the caravan

- Enslaved people who carried goods and provided labor (reflecting the tragic reality of slavery in medieval societies)

500 slaves, each carrying a golden staff weighing approximately 6 pounds (about 2.7 kg), walked ahead of Mansa Musa—a display of wealth so ostentatious it stunned observers.

100 camels, each carrying 300 pounds of gold dust (about 136 kg per camel)—meaning the caravan transported approximately 13,600 kg or about 15 tons of gold. At current prices, this gold alone would be worth over $800 million.

Thousands of additional camels and horses carried supplies, food, water, trade goods, and personal belongings.

Lavish tents, furnishings, and luxury goods ensured that Mansa Musa traveled in royal comfort despite the harsh conditions.

The Journey Through Egypt: Making Mali Famous

The most detailed accounts of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage come from his stopover in Cairo, Egypt, which was at that time one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the Islamic world. His visit there would have lasting economic and political consequences.

Mansa Musa arrived in Cairo in July 1324, where he stayed for approximately three months. His presence created a sensation in the city.

The Display of Generosity—and Its Consequences

Mansa Musa distributed gold with extraordinary—some would say reckless—generosity:

He gave gold to virtually everyone he encountered:

- Poor people in the streets received gold

- Merchants conducting business received gold

- Religious institutions and mosques received substantial donations

- Government officials received lavish gifts

- Scholars and students received patronage

The amounts were staggering. Contemporary historian Al-Umari, who visited Cairo twelve years after Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage, wrote that the king gave away so much gold that the price of gold in Cairo declined sharply and took over a decade to recover.

This wasn’t just generosity—it was economic disruption. When the supply of gold suddenly increased dramatically, its value decreased relative to other goods (basic inflation economics). The gold standard that governed medieval commerce was thrown into chaos. Prices in Cairo rose sharply as gold became less valuable, creating hardship for ordinary people whose savings in gold suddenly bought less than before.

Historians estimate that Mansa Musa may have distributed 18-20 tons of gold during his entire journey—an almost incomprehensible amount of wealth.

Realizing his mistake, Mansa Musa attempted to stabilize the situation on his return journey through Cairo by borrowing gold from Egyptian moneylenders at high interest rates, effectively removing some gold from circulation. However, the economic impact of his generosity lasted for years, a testament to just how much wealth he had distributed.

Diplomatic and Cultural Impact

Beyond the economic effects, Mansa Musa’s time in Cairo served important diplomatic and cultural purposes:

He met with the Mamluk Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, one of the most powerful rulers in the Islamic world. This meeting established Mali as a recognized power in Islamic diplomacy.

He impressed Egyptian scholars and officials with his piety, knowledge of Islam, and administrative sophistication, challenging any assumptions they might have held about West Africans as unsophisticated or uncivilized.

He recruited scholars, architects, and religious teachers to return with him to Mali, particularly attracting es-Saheli (also known as Abu Ishaq al-Sahili), a renowned Andalusian architect and poet who would design important buildings in Mali.

He established Mali’s reputation throughout the Islamic world, ensuring that West African gold would be taken even more seriously in international commerce.

Stories of his wealth spread rapidly through both Islamic and Christian Mediterranean trade networks, eventually reaching European courts and contributing to European interest in African gold that would later fuel the Age of Exploration.

The Holy Cities: Mecca and Medina

After leaving Egypt, Mansa Musa’s caravan continued eastward through the Sinai Peninsula and into Arabia, the ultimate destination being Mecca.

In Mecca and Medina, Mansa Musa performed the rituals of hajj:

The Tawaf (circumambulating the Kaaba seven times) Sa’i (walking between the hills of Safa and Marwa) Standing at Arafat (the most important ritual of hajj) Symbolic stoning of the devil at Mina Visiting the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina

Mansa Musa’s presence in the holy cities was noted by pilgrims from across the Islamic world, further spreading Mali’s fame. His generosity continued, with substantial donations to support the maintenance of holy sites and provide charity to poor pilgrims.

The spiritual dimension of this journey was genuinely important to Mansa Musa. While the pilgrimage certainly served political and economic purposes, the historical record suggests his faith was sincere. He was following in the footsteps of millions of Muslims who had made this journey before him, fulfilling what he believed was a religious obligation and seeking spiritual merit.

The Return Journey: Bringing Knowledge Home

The return journey through Egypt and across the Sahara back to Mali took many more months, but Mansa Musa returned with more than just memories and spiritual fulfillment.

He brought back scholars and experts, including the architect es-Saheli, who would transform Mali’s architectural landscape by introducing new building techniques and designs.

He carried books, manuscripts, and scholarly works that would enrich Mali’s libraries and educational institutions.

He had established relationships and trade contacts that would benefit Mali’s commerce for years to come.

Most importantly, he returned with enhanced prestige—not just for himself personally, but for Mali as an empire and for West Africa more broadly. The pilgrimage had announced to the medieval world that Mali was a power to be reckoned with, wealthy beyond imagination, and sophisticated in its governance and culture.

Economic Influence: Mali’s Golden Age

The Source of Wealth: Gold Production and Control

Mansa Musa’s legendary wealth was not simply inherited or acquired through conquest—it was the result of Mali’s control over some of the richest gold deposits in the medieval world and the sophisticated systems that extracted, processed, and traded this precious metal.

The gold-producing regions under Mali’s control included:

Bambuk: Located in the upper Senegal River region (between modern Senegal and Mali), Bambuk was one of West Africa’s richest gold-mining areas. Its deposits were extensive and relatively easy to access.

Bure: Located in the upper Niger River region (in modern Guinea), Bure’s gold deposits were even richer than Bambuk’s. The region’s mines produced vast quantities of gold throughout the medieval period.

Galam: Another significant gold-producing region, contributing to Mali’s overall gold supply.

The mining operations in these regions were sophisticated:

Alluvial mining (panning for gold in rivers and streams) was the primary method, taking advantage of erosion that had washed gold from underground deposits into waterways.

Some shaft mining was also practiced, with miners digging deep pits to reach gold-bearing rocks.

The labor was intensive, involving thousands of workers in organized operations.

Local communities managed mining, with Mali’s government collecting tribute and taxes rather than directly controlling all operations.

The Secret Trade: Gold Production Mysteries

One fascinating aspect of Mali’s gold trade was the secrecy surrounding its source. North African and European merchants desperately wanted to know where West African gold came from, hoping to bypass middlemen and trade directly with producers. However, Mali carefully guarded this information.

The “silent trade” tradition (also called “dumb barter”) was practiced in some regions:

- Merchants would leave goods at designated trading spots

- Gold producers would come, examine the goods, and leave a quantity of gold they deemed fair

- Merchants would return and either accept the trade or leave more goods

- This process continued until both parties were satisfied

- Crucially, the two groups never met face-to-face, preserving the anonymity of gold producers

This secrecy served Mali’s economic interests by maintaining the kingdom’s role as intermediary in the gold trade, ensuring that all gold had to pass through Mali’s taxation system before reaching trans-Saharan merchants.

Timbuktu and Gao: Commercial Capitals

Under Mansa Musa’s rule, Timbuktu and Gao transformed from important regional centers into major commercial metropolises that attracted merchants from three continents.

Timbuktu: Where the Desert Meets the River

Timbuktu’s strategic location made it ideal as a trading hub:

- Positioned where trans-Saharan caravan routes met the Niger River

- Served as a transshipment point where goods moved from camels to boats or vice versa

- Five miles from the Niger’s main channel, Timbuktu was connected by a canal, providing river access while being positioned far enough from the river to avoid flooding

The markets of Timbuktu were legendary:

Gold markets where West African gold was exchanged for salt and other goods brought from the Sahara

Salt markets where massive slabs of Saharan salt (sometimes weighing 90 kg or 200 pounds each) were bought by merchants supplying West African regions

Textile markets featuring cloth from North Africa, Egypt, and even as far away as India and China, exchanged for West African goods

Book markets where manuscripts and written works were bought and sold—Timbuktu became famous for its book trade, with some manuscripts worth more than many other trade goods

Slave markets where enslaved people from various regions were tragically bought and sold—a grim reminder of the human cost of medieval commerce

Markets for luxury goods including ivory, exotic woods, kola nuts, leather goods, and other valuable items

Mansa Musa invested heavily in Timbuktu’s infrastructure:

The Djinguereber Mosque (completed 1327), designed by the architect es-Saheli whom Mansa Musa brought back from his pilgrimage, became Timbuktu’s most famous landmark.

The Sankore Mosque and University, expanded under Mansa Musa’s patronage, became one of Africa’s greatest centers of learning.

Caravanserais (lodging houses for traveling merchants) provided accommodation and secure storage.

Markets and commercial infrastructure facilitated trade and made Timbuktu more attractive to merchants.

Royal palaces and administrative buildings demonstrated Mali’s power and wealth.

Gao: The Eastern Gateway

After conquering Gao in 1325, Mansa Musa developed it as Mali’s eastern commercial center:

Gao controlled trade routes extending eastward toward the Lake Chad region and Hausa states, connecting Mali to additional commercial networks.

The city served as a military and administrative center for Mali’s eastern provinces, ensuring security in the region.

Its position on the Niger River made it a crucial point for river commerce moving up and down the middle Niger.

Gao’s markets complemented Timbuktu’s, creating a commercial network that made Mali the center of West African trade.

The Economics of Empire: Taxation and Administration

Mali’s vast wealth wasn’t simply dug out of the ground—it was the result of sophisticated economic administration:

Taxation of trade was Mali’s primary revenue source beyond direct control of gold-producing regions:

- Merchants passing through Mali’s territory paid customs duties

- Taxes on goods moving through markets generated substantial income

- Different goods were taxed at different rates, with luxury items often paying higher percentages

Tribute from subject territories provided additional wealth:

- Conquered regions paid annual tribute in gold, goods, or military service

- Local rulers who acknowledged Mali’s supremacy sent regular payments

- This system allowed Mali to benefit from territories without direct administration

Royal monopolies on certain trade goods increased royal revenue:

- The most valuable items sometimes could only be traded through royal agents

- This ensured the mansa personally profited from the most lucrative commerce

Agricultural taxation on farming communities throughout the empire:

- Taxes were paid in crops, livestock, or labor service

- This provided food security for urban centers and military forces

The administrative system that collected and managed these revenues was sophisticated for its time:

- Regional governors (farbas) oversaw tax collection in their territories

- Record-keeping systems (likely oral rather than written, maintained by specialists) tracked tribute and taxation

- Royal treasuries in major cities stored wealth and distributed it according to the mansa’s directions

This economic system generated wealth that allowed Mansa Musa to:

- Maintain a large standing army

- Fund public works and building projects

- Support scholars, religious institutions, and educational facilities

- Conduct diplomacy and maintain international relationships

- Display generosity that enhanced his reputation (as in his famous pilgrimage)

Mali on the World Stage: International Recognition

The impact of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage and Mali’s wealth extended far beyond West Africa:

The Catalan Atlas (1375), created for King Charles V of France, included a detailed depiction of Mansa Musa seated on a throne, holding a gold nugget and wearing a crown. This map, one of the most important medieval European maps, shows Mansa Musa as the most prominent figure in the entire African continent, testifying to his fame in Europe decades after his death.

European merchants and rulers became increasingly interested in accessing West African gold directly, eventually contributing to Portuguese exploration down the West African coast in the 15th century.

Arab and North African chronicles extensively documented Mali’s wealth and Mansa Musa’s reign, ensuring his place in Islamic historical memory.

Mali’s diplomatic relationships extended to Egypt, Morocco, and other Islamic powers, with Mali recognized as a legitimate and important state in medieval international relations.

The phrase “rich as Mansa Musa” entered into language across North Africa and the Middle East, becoming proverbial for incomprehensible wealth.

Cultural and Educational Legacy: The African Renaissance

Timbuktu’s Transformation: The University City of Africa

While Mansa Musa is famous for his wealth, his most enduring legacy may be his transformation of Timbuktu into one of the great intellectual centers of the medieval world—a reputation that would last for centuries and make the city synonymous with scholarship and learning.

When Mansa Musa returned from his pilgrimage in 1325, he brought with him the architect and poet es-Saheli (Abu Ishaq al-Sahili), an Andalusian scholar who would revolutionize architecture in Mali. Es-Saheli introduced new building techniques, including:

Burnt brick construction rather than traditional mud-brick or adobe More sophisticated architectural designs influenced by Andalusian and Egyptian styles Innovative structural approaches that allowed for larger, more impressive buildings

The architectural legacy of this partnership includes:

Djinguereber Mosque (1327): This magnificent structure, still standing today, became Timbuktu’s most famous landmark. Its distinctive pyramidal minarets and imposing presence symbolized both Mali’s Islamic faith and its architectural sophistication.

The Sankore Mosque and University complex: Expanded and beautified under Mansa Musa’s patronage, Sankore became the heart of Timbuktu’s educational system.

Royal palaces and administrative buildings: These demonstrated Mali’s wealth and power while providing functional spaces for governance.

The Gao Palace: Built in Mali’s eastern capital after its conquest, showing that Mansa Musa’s architectural patronage extended throughout his empire.

The University of Sankore: Africa’s Intellectual Powerhouse

The University of Sankore, under Mansa Musa’s patronage, became one of the world’s great medieval universities, comparable to prestigious institutions in Cairo (Al-Azhar), Baghdad, Cordoba, and Paris.

The scale of Sankore’s operation was impressive:

25,000 students at its peak, according to some estimates—an enormous student body for the medieval period

Hundreds of scholars and teachers from throughout the Islamic world, making Sankore truly international

Extensive library collections housed in Sankore and throughout Timbuktu, eventually totaling hundreds of thousands of manuscripts

A rigorous curriculum that required years of study before students could be considered fully educated

The Curriculum: What Was Taught

Sankore’s curriculum reflected the breadth of Islamic medieval scholarship:

Islamic Studies formed the core:

- Quran memorization, interpretation, and recitation

- Hadith (sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad)

- Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence and law)

- Tafsir (Quranic exegesis and commentary)

- Aqidah (Islamic theology and beliefs)

Mathematics and Arithmetic:

- Advanced mathematical concepts including algebra and geometry

- Practical mathematics for commerce, taxation, and astronomy

- Number theory and mathematical problems

Astronomy:

- Calculation of prayer times and determination of Qibla (direction of Mecca)

- Creation of astronomical tables

- Understanding of celestial movements and calendars

Medicine:

- Traditional Islamic and African medical knowledge

- Herbal medicines and treatments

- Anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment protocols

- Medical ethics

Logic and Philosophy:

- Greek philosophical works translated into Arabic

- Islamic philosophical traditions

- Logical reasoning and debate techniques

Grammar, Rhetoric, and Poetry:

- Arabic language mastery (essential for Quranic study)

- Literary composition and analysis

- Poetry composition in Arabic and local languages

History and Geography:

- Islamic history and biography

- Regional African history

- Geography of the Islamic world and trade routes

Law and Administration:

- Sharia (Islamic law) and its application

- Administrative principles and governance

- Contract law and commercial regulations

The Manuscripts: Preserving Knowledge

Timbuktu’s libraries housed an estimated 400,000 to 700,000 manuscripts at the height of Mali’s intellectual culture. While many have been lost to time, warfare, and environmental damage, tens of thousands survive today, providing invaluable insights into medieval African scholarship.

These manuscripts cover virtually every field of knowledge:

Religious texts including Quranic commentaries, hadith collections, and works on Islamic law

Scientific works on astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and natural philosophy

Historical chronicles documenting West African history, biographies of leaders, and accounts of major events

Legal documents including court records, contracts, and correspondence

Literary works including poetry, prose, and philosophical treatises

Practical manuals on topics ranging from agriculture to trade to diplomacy

The survival of these manuscripts proves that medieval West Africa had a sophisticated literary culture and challenges outdated narratives about Africa lacking written traditions. Modern conservation efforts, particularly by the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu and international partners, work to preserve these priceless historical documents.

The Spread of Islam: Faith and Governance

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage and his patronage of Islamic scholarship accelerated the Islamization of West Africa, though this process had begun before his reign and would continue after it.

His approach to promoting Islam was sophisticated:

He did not forcibly convert his subjects. While Mansa Musa was a devout Muslim and promoted Islamic practices, he recognized that much of his empire’s population still practiced traditional African religions. Forced conversion would have destabilized his rule and sparked rebellions.

Instead, he promoted Islam through example and incentive:

- Royal patronage of mosques and Islamic scholars

- Appointment of Muslims to important administrative positions

- Support for Islamic education

- His own ostentatious display of Muslim piety during the pilgrimage

He blended Islamic governance with traditional African political systems:

- Islamic law (Sharia) governed some aspects of life, particularly commerce and religious matters

- Traditional African legal customs and practices continued in many areas

- Local rulers maintained traditional ceremonies and rituals alongside Islamic observances

- This syncretism (blending of traditions) allowed Islam to spread without completely replacing existing cultural practices

The result was a distinctive West African Islamic culture that combined Islamic beliefs and practices with African traditions, creating something unique that was neither purely Arab/Middle Eastern Islam nor purely traditional African religion, but a synthesis of both.

Cultural Flourishing: Arts and Literature

Mansa Musa’s patronage extended beyond religious and academic institutions to support broader cultural development:

Griots (traditional oral historians and musicians) continued their important role in West African society, preserving history and culture through oral tradition. Under Mansa Musa’s patronage, they also began incorporating Islamic elements into their repertoire.

Architecture flourished, with the distinctive Sudano-Sahelian style (featuring mud-brick construction, flat roofs, and distinctive decorative elements) evolving and spreading.

Textile production reached high levels of sophistication, with Mali famous for its woven fabrics and leather goods.

Metallurgy and craftsmanship produced high-quality tools, weapons, jewelry, and decorative items.

This cultural flowering made Mali not just wealthy but also culturally sophisticated, contributing to its reputation as one of the great civilizations of the medieval world.

The Legacy of Mansa Musa: Lasting Impact on Africa and the World

Immediate Impact: Mali’s Golden Age Continues

Mansa Musa died in 1337, having ruled for 25 years. While specific details of his death are not recorded in surviving sources, he left behind an empire at the height of its power and prosperity.

His immediate successors inherited:

The largest and wealthiest empire in Africa, controlling vast territories and trade routes

A sophisticated administrative system capable of governing this large territory

Military forces that could defend Mali’s borders and maintain internal order

Diplomatic relationships with powers throughout the Islamic world

Educational and cultural institutions that would continue operating for centuries

The Mali Empire remained dominant in West Africa for over a century after Mansa Musa’s death, though it would gradually decline in the 15th century due to succession disputes, external pressure from emerging powers like Songhai, and the inherent challenges of maintaining such a large empire.

Influence on Subsequent West African Empires

The Songhai Empire (c. 1464-1591), which eventually displaced Mali as the dominant power in West Africa, built directly on Mali’s foundations:

Songhai rulers adopted many of Mali’s administrative practices, recognizing their effectiveness.

Timbuktu and Gao remained major centers of learning and commerce under Songhai rule, continuing the traditions Mansa Musa had established.

The Songhai Empire maintained and expanded the educational institutions that Mansa Musa had patronized.

Askia Muhammad I (r. 1493-1528), one of Songhai’s greatest rulers, explicitly modeled himself on Mansa Musa, undertaking his own elaborate pilgrimage to Mecca (1496-1497) and promoting Islamic scholarship.

Challenging Stereotypes: African Civilizations in World History

Perhaps Mansa Musa’s most important legacy is how his reign challenges persistent misconceptions about African history:

The myth of “primitive” Africa is demolished by the sophistication of Mali’s governance, economy, military organization, and cultural achievements.

The false narrative that Africa lacked written traditions is refuted by the hundreds of thousands of manuscripts produced and preserved in Timbuktu and other West African centers of learning.

The stereotype of Africa as isolated from global history is contradicted by Mali’s extensive trade networks connecting it to North Africa, the Middle East, and indirectly to Europe and Asia.

The misconception that Africa lacked wealth is obviously false—Mali under Mansa Musa was wealthier than any contemporary European kingdom.

The assumption that African societies were small-scale ignores empires like Mali that controlled territory and populations comparable to major powers elsewhere in the world.

Mansa Musa’s story proves that medieval Africa was home to sophisticated civilizations that were in many ways more advanced than contemporary European societies. While Europe struggled through the 14th century (including the devastating Black Death plague that killed one-third of Europe’s population), West Africa was experiencing a golden age of prosperity, learning, and cultural achievement.

Modern Relevance and Memory

Mansa Musa’s legacy continues to resonate in the 21st century:

In African Identity and Pride

Mansa Musa has become a symbol of African achievement and a source of pride for people of African descent worldwide. His story counters narratives of African inferiority and demonstrates the continent’s rich historical legacy.

Educational initiatives in Africa and the African diaspora highlight Mansa Musa’s accomplishments to inspire young people and provide historical role models.

Cultural movements reference Mansa Musa as an icon of Black excellence and African greatness.

In Popular Culture

Mansa Musa appears frequently in modern media:

Books and documentaries explore his life and Mali’s history Music and hip-hop reference “Mansa Musa money” as a symbol of wealth Video games (like Civilization VI) include Mansa Musa as a playable leader Art and visual culture depict Mansa Musa in various contexts

In Economic and Historical Discourse

Economists and financial writers discuss Mansa Musa when examining historical wealth and economic power, often citing him as “the richest person in history.”

Historians use his reign as a case study in medieval African history, trade networks, and Islamic civilization.

His legacy contributes to broader understanding of global medieval history beyond the traditional Eurocentric focus.

The Physical Legacy: What Remains

Physical evidence of Mansa Musa’s legacy can still be found:

The Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, built during his reign, still stands and remains in use today—a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Sankore Mosque, another UNESCO site, continues Mali’s educational traditions.

Manuscript collections in Timbuktu preserve knowledge from Mansa Musa’s era, with ongoing conservation efforts protecting these irreplaceable documents.

Archaeological sites throughout Mali reveal evidence of the empire’s prosperity and sophistication.

Oral traditions maintained by griots preserve stories and histories of Mansa Musa’s reign, passed down through generations.

Lessons for Today

Mansa Musa’s story offers lessons that remain relevant:

The connection between security and prosperity: Mali’s trade flourished because Mansa Musa’s military protected commerce, showing how security and economic growth are interrelated.

Investment in education pays long-term dividends: Mansa Musa’s patronage of learning created institutions that lasted centuries and generated intangible benefits far beyond their immediate cost.

Cultural sophistication matters in international relations: Mali’s reputation for wealth and learning made it respected globally, demonstrating that “soft power” matters.

Diversity can be strength: Mali’s integration of different peoples, regions, and traditions created a large, stable empire rather than forcing complete uniformity.

Historical memory shapes present identity: How we remember and interpret figures like Mansa Musa influences contemporary understanding of Africa’s place in world history.

Conclusion: The Warrior King Who Changed Africa

Mansa Musa’s reign from 1312 to 1337 represents the apex of West African civilization during the medieval period. He was more than just a wealthy king—he was a military strategist who expanded his empire to unprecedented size, a cultural patron who transformed Timbuktu into a global center of learning, a devout Muslim who promoted Islamic scholarship while respecting traditional African practices, and a diplomatic genius whose legendary pilgrimage announced Mali’s greatness to the world.

His military achievements secured Mali’s borders, expanded its territory, protected its vital trade routes, and ensured the security necessary for economic and cultural flourishing.

His economic policies managed vast wealth effectively, making Mali the richest empire in Africa and one of the wealthiest in the world while generating revenue that supported his ambitious projects.

His cultural patronage created educational institutions that rivaled the greatest universities of the medieval world, preserved and advanced human knowledge, and made Timbuktu synonymous with scholarship and learning.

His diplomatic accomplishments established Mali as a recognized power in the Islamic world, created trade and political relationships that benefited his empire, and spread Mali’s fame throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Most importantly, Mansa Musa’s legacy challenges us to reconsider African history. His reign proves that medieval Africa was not a dark continent awaiting European enlightenment, but rather home to sophisticated civilizations that were wealthy, learned, and powerful. The Mali Empire under Mansa Musa was more prosperous than most European kingdoms, more supportive of education than many contemporary societies, and more connected to global trade networks than often acknowledged.

For modern Africa, Mansa Musa represents a glorious past that provides inspiration and pride. His story reminds Africans and people of African descent that their ancestors built great civilizations, controlled vast wealth, pursued knowledge and scholarship, and participated fully in medieval global civilization.

For students of world history, Mansa Musa’s reign is essential for understanding the medieval world beyond Europe, recognizing Africa’s central role in global trade networks, and appreciating the diversity of human civilizations and achievements.

For anyone interested in exceptional leadership, Mansa Musa demonstrates how military power, economic management, cultural patronage, and diplomatic skill can combine to create lasting impact and transform societies.

Nearly 700 years after his death, Mansa Musa remains one of history’s most fascinating figures—a warrior king whose wealth was legendary, whose empire was vast, whose cultural patronage was generous, and whose legacy continues to inspire and educate. He elevated the Mali Empire to greatness and, in doing so, demonstrated the sophistication and achievements of African civilization to the world.

Additional Resources

For those interested in learning more about Mansa Musa and the Mali Empire:

- The British Library’s collection features manuscripts and artifacts from West African kingdoms, including the Mali Empire

- UNESCO’s World Heritage listing for Timbuktu provides historical context and information about ongoing preservation efforts