Table of Contents

Tomoe Gozen: The Legendary Female Samurai and Her Influence on Japan

Introduction: Between History and Legend

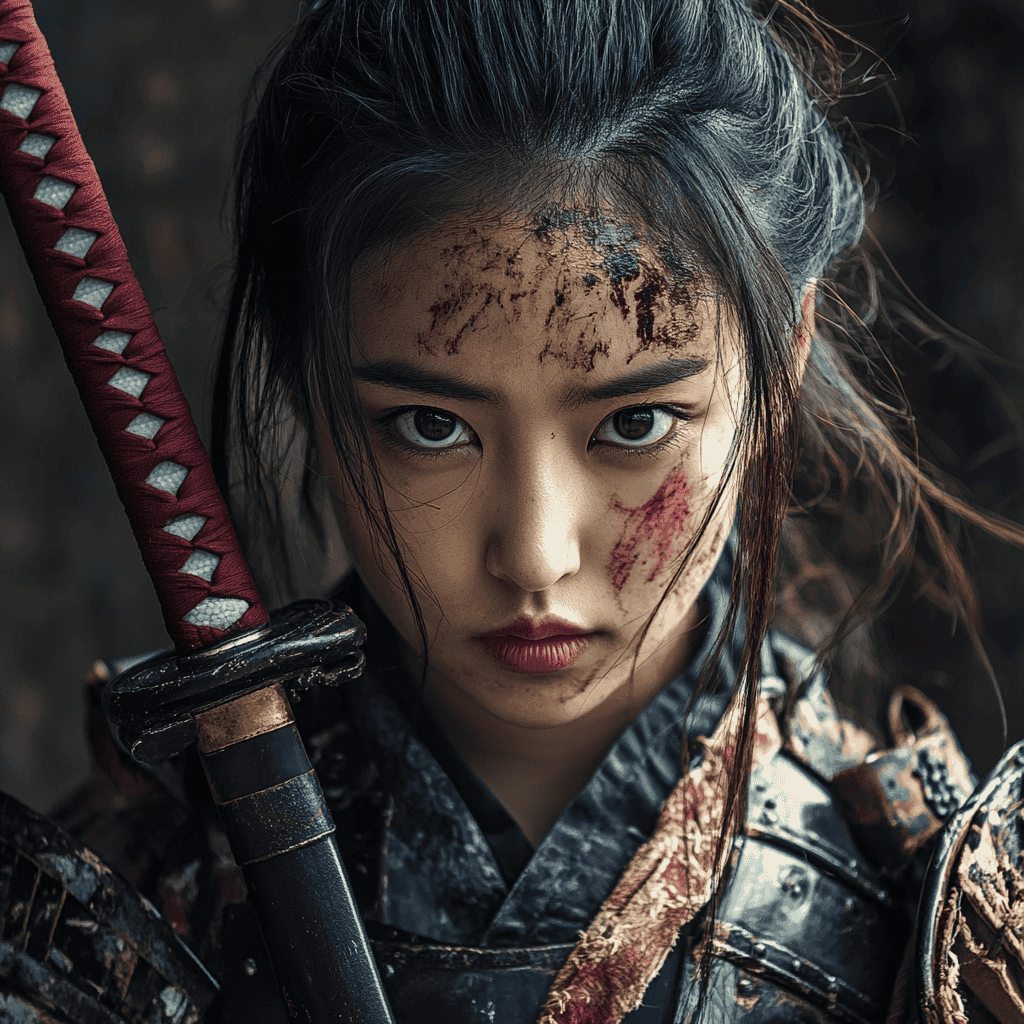

Tomoe Gozen stands as one of the most enigmatic and compelling figures in Japanese history—a woman whose very existence remains debated by scholars, yet whose legend has profoundly influenced Japanese culture for over 800 years. Described in medieval chronicles as a fearsome warrior who fought in the Genpei War (1180–1185), she represents something extraordinary: a woman who allegedly commanded troops, excelled in combat, and earned fame in a society where warfare was overwhelmingly a male domain.

The challenge in writing about Tomoe Gozen is that we must navigate the murky boundary between historical fact and literary legend. The primary source for her story is “The Tale of the Heike” (Heike Monogatari), a 13th-century epic chronicle of the Genpei War that blends historical events with artistic embellishment. Did Tomoe Gozen exist as described—a warrior of exceptional skill who fought alongside her master Minamoto no Yoshinaka in crucial battles? Or is she a literary creation, an idealized figure reflecting cultural values about loyalty, courage, and feminine strength?

Most historians today conclude that someone named Tomoe likely existed, and she probably had some martial role in Yoshinaka’s household. However, the extent of her battlefield exploits, the specific deeds attributed to her, and many details of her life remain impossible to verify with certainty. The historical Tomoe and the legendary Tomoe have merged into a single powerful cultural figure whose “truth” extends beyond mere factual accuracy.

What makes Tomoe Gozen historically significant is not just her possible battlefield achievements, but what her legend reveals about Japanese culture: attitudes toward women warriors, the values encoded in samurai traditions, the role of gender in feudal society, and how stories shape cultural identity across centuries. Her tale challenges simplistic narratives about women’s roles in medieval Japan while also reflecting the limitations and expectations that constrained female agency.

In modern times, Tomoe Gozen has experienced a remarkable revival, becoming an icon for feminist movements in Japan, a popular character in anime, manga, and video games, and a symbol invoked in discussions about women’s empowerment and gender roles. This contemporary reimagining of Tomoe demonstrates how historical (or legendary) figures can be reinterpreted to speak to new generations facing different challenges.

This comprehensive exploration examines what we know and don’t know about the historical Tomoe Gozen, analyzes the context of women warriors in medieval Japan, explores how her legend developed and influenced Japanese culture, and considers her modern significance as both a historical figure and a cultural symbol. Her story reveals the complex intersections of history, legend, gender, and cultural memory in shaping how societies understand their past.

Understanding the Historical Context: The Genpei War

The Conflict That Defined an Era (1180-1185)

To understand Tomoe Gozen’s story, we must first grasp the Genpei War—a catastrophic conflict that transformed Japanese politics and culture, marking the transition from aristocratic court rule to samurai military government.

The Genpei War was a power struggle between two great warrior clans:

The Taira clan (also called Heike), which had gained dominance at the imperial court through military service and political maneuvering, effectively controlling the emperor and government by the 1170s.

The Minamoto clan (also called Genji), which had been the Taira’s primary rival but was brutally suppressed in 1160, with many Minamoto leaders killed and their sons exiled or spared as children.

By 1180, resentment against Taira dominance had built among aristocrats, Buddhist institutions, and provincial warriors who felt excluded from power or oppressed by Taira policies.

The conflict began in 1180 when Prince Mochihito issued a call for the Minamoto and other warriors to rise against the Taira. Though Prince Mochihito was quickly killed, his call to arms ignited a nationwide civil war that would rage for five years.

The war was characterized by:

Brutal warfare across Japan, with battles, sieges, and raids devastating the countryside

Shifting alliances as provincial warlords chose sides based on advantage

Naval warfare in the Inland Sea, where the Taira’s maritime strength initially gave them advantage

Religious institutions taking sides, with monasteries raising warrior-monk armies

The eventual Minamoto victory in 1185 led to the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate, Japan’s first military government, fundamentally changing Japanese political structure for centuries.

Minamoto no Yoshinaka: Tomoe’s Master

Minamoto no Yoshinaka was a complex figure whose rise and fall provide the context for Tomoe Gozen’s story.

Yoshinaka was a cousin of Minamoto no Yoritomo (who would eventually become shogun) and had been raised in the mountainous Kiso region after his father’s death, earning him the nickname “Kiso Yoshinaka.”

His role in the Genpei War unfolded in phases:

1180-1183: Rise to Power

- Yoshinaka raised forces in response to Prince Mochihito’s call

- He achieved significant victories against Taira forces in northern Japan

- His successes made him a major Minamoto leader alongside his cousin Yoritomo

1183: Triumphant Entry into Kyoto

- Yoshinaka’s forces drove the Taira from the capital Kyoto

- He was celebrated as a hero who had liberated the court

- He received appointments and honors from the emperor

1183-1184: Fall from Grace

- Yoshinaka’s rustic provincial warriors behaved badly in sophisticated Kyoto, alienating courtiers

- Political conflicts with his cousin Yoritomo intensified

- Yoshinaka’s attempts to claim imperial authority threatened Yoritomo’s supremacy

- His forces began committing depredations that destroyed his reputation

January 1184: Death at the Battle of Awazu

- Yoritomo sent forces under his brothers to destroy Yoshinaka

- Yoshinaka, his army disintegrating, made a last stand at Awazu

- He was killed in battle at age 31

It is during this final period that Tomoe Gozen appears prominently in the historical records—or rather, in “The Tale of the Heike,” our primary source for her story.

The Historical Evidence: What We Know and Don’t Know

The Tale of the Heike: Our Primary Source

“The Tale of the Heike” (Heike Monogatari) is a 13th-century epic—Japan’s equivalent to Homer’s Iliad or the Song of Roland—that recounts the Genpei War with a mixture of historical events and literary artistry.

The text was originally performed by blind traveling musicians who recited it to musical accompaniment, making it part oral history, part entertainment, and part moral instruction about the impermanence of power and the importance of Buddhist values.

The description of Tomoe Gozen in “The Tale of the Heike” is brief but vivid:

“Tomoe was especially beautiful, with white skin, long hair, and charming features. She was also a remarkably strong archer, and as a swordswoman she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot. She handled unbroken horses with superb skill; she rode unscathed down perilous descents. Whenever a battle was imminent, Yoshinaka sent her out as his first captain, equipped with strong armor, an oversized sword, and a mighty bow; and she performed more deeds of valor than any of his other warriors.”

This description establishes Tomoe as:

- Exceptionally beautiful

- Highly skilled in archery and swordsmanship

- Capable of riding difficult horses

- Serving as a captain of troops

- Performing remarkable military feats

The text then describes her role in Yoshinaka’s final battle:

Yoshinaka, with only a handful of warriors remaining, orders Tomoe to flee because “it would be unseemly to die with a woman.”

Tomoe initially refuses but eventually agrees to leave after performing one final deed of valor.

She charges into enemy forces, grapples with a renowned warrior (Honda no Moroshige or Onda no Hachiro Moroshige, depending on the version), pulls him from his horse, pins him against her saddle, cuts off his head, then rides away and disappears from history.

This dramatic exit—simultaneously martial and mysterious—has captivated readers for centuries, contributing to Tomoe’s legendary status.

Other Historical References

Beyond “The Tale of the Heike,” evidence for Tomoe is sparse:

“Genpei Jōsuiki” (another chronicle of the Genpei War) mentions Tomoe and provides slightly different details about her exploits.

Some genealogies and local traditions in the Kiso region claim to preserve information about her later life (some suggesting she married and lived quietly after Yoshinaka’s death, others that she became a nun).

No contemporary documents from the 1180s specifically mention Tomoe—our earliest sources date from decades after the events they describe.

Official military records don’t include her name, though this is unsurprising given record-keeping practices and gender expectations of the era.

The Historical Debate: Did Tomoe Exist?

Scholars divide into roughly three camps:

Skeptics argue Tomoe is a literary invention, created to serve narrative purposes—representing loyalty, feminine strength, or tragic romance. They note the lack of contemporary documentation and the literary qualities of her description.

Moderates (probably the majority of current scholars) believe someone named Tomoe existed and had some martial role in Yoshinaka’s household, but that her specific exploits were exaggerated or invented by later chroniclers.

Believers accept “The Tale of the Heike” as generally reliable regarding Tomoe’s existence and martial achievements, noting that the chronicle preserves genuine historical information despite its literary embellishments.

The truth likely lies somewhere in the middle—there probably was a woman named Tomoe associated with Yoshinaka who had martial training and possibly participated in combat, but the specific deeds attributed to her may reflect a combination of fact, exaggeration, and literary artistry.

For this article, we’ll acknowledge this ambiguity while exploring both the possible historical reality and the definite legendary tradition that developed around her.

Women Warriors in Medieval Japan: The Broader Context

The Onna-Musha Tradition

Tomoe Gozen was not as anomalous as we might initially think. Medieval Japan had a tradition of onna-musha (female warriors) or onna-bugeisha (women martial artists) who received weapons training and sometimes participated in combat.

The context for female martial training included:

Defense of households and estates when men were away at war—women needed to protect homes, children, and property from bandits or enemy forces.

Family honor could require women to defend themselves or their children from assault or capture.

Suicide ritual (jigai) in case of impending capture sometimes required skill with blades.

Social status among samurai families might be demonstrated through martial training for both sons and daughters.

The Naginata: The Woman Warrior’s Weapon

The naginata became particularly associated with female warriors:

A naginata is a pole weapon with a curved blade at the end—essentially a sword mounted on a long shaft, providing reach and leveraging strength efficiently.

The weapon offered several advantages for women:

- Reach allowed keeping opponents at distance, compensating for potential strength differences

- Leverage from the long shaft multiplied striking power

- Technique could substitute for brute strength

- Versatility allowed both cutting and thrusting attacks

By the Edo period (1603-1868), naginata training was standard for upper-class women, though by this time it was more ceremonial and educational than practical.

Tomoe Gozen is described as skilled with various weapons (bow, sword, and horsemanship), suggesting broader martial training than just naginata—which makes sense if she actually served in military capacity rather than just home defense.

Other Historical Women Warriors

Tomoe Gozen wasn’t the only woman warrior in Japanese history:

Empress Jingū (c. 169-269, possibly legendary) was said to have led a military campaign to Korea while pregnant.

Hangaku Gozen (late 12th-early 13th century) was a contemporary of Tomoe who defended a castle during a siege, killing numerous enemies before being captured.

Hōjō Masako (1157-1225), though not a battlefield warrior, wielded significant political and military power, earning the title “nun shogun.”

Nakano Takeko (1847-1868) led a unit of female warriors in the Boshin War, dying in combat at age 21.

Numerous less-famous women participated in castle defenses, local conflicts, and martial training throughout Japanese history.

This broader context suggests that while women warriors were uncommon, they weren’t unprecedented or culturally impossible in medieval Japan.

The Legend Develops: Tomoe in Literature and Art

Medieval Literature: Establishing the Archetype

“The Tale of the Heike” established Tomoe as an archetype that later works would elaborate upon:

Her combination of beauty and martial prowess became a recurring motif—the warrior woman had to be both aesthetically pleasing and frighteningly effective.

Her loyalty to Yoshinaka even unto death reflected the highest ideals of samurai devotion.

Her mysterious disappearance created narrative space for later writers to imagine her fate.

Subsequent medieval works expanded on her story:

Noh theater incorporated Tomoe into plays about the Genpei War, sometimes depicting her as a ghost haunted by her warrior past.

Various chronicles and war tales added details, sometimes contradicting each other, creating a complex legendary tradition.

Buddhist-influenced interpretations sometimes portrayed her as renouncing the world to become a nun, achieving spiritual peace after a life of violence.

Edo Period (1603-1868): Artistic Flourishing

During the Edo period, Tomoe Gozen became a popular subject in various art forms:

Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints

Master artists created striking images of Tomoe:

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) produced famous prints showing Tomoe in dramatic battle scenes, her beauty emphasized even as she defeats male opponents.

The aesthetic combined feminine grace with martial ferocity—a distinctly Japanese approach to depicting women warriors.

These prints often showed Tomoe:

- In elaborate armor with flowing robes

- Wielding naginata or bow

- Defeating male warriors, sometimes while maintaining serene expression

- Accompanied by descriptive text recounting her exploits

Kabuki Theater

Kabuki plays featuring Tomoe became popular entertainment:

Male actors in female roles (onnagata) portrayed Tomoe, requiring sophisticated performance to convey both femininity and warrior strength.

Dramatic scenes emphasized her loyalty, martial skill, and tragic fate.

The plays often elaborated on her relationship with Yoshinaka, adding romantic elements not present in original sources.

Meiji Period (1868-1912): National Symbol

During the Meiji period, as Japan modernized and grappled with Western influence, Tomoe took on new meanings:

Nationalists invoked her as an example of traditional Japanese warrior spirit and loyalty.

Women’s education reformers used her story to argue for physical education and martial training for girls.

Historical novelists created elaborate narratives about her life, filling in gaps in the historical record with imaginative detail.

She became part of the pantheon of historical figures used to define Japanese national identity during this period of rapid change.

Cultural Significance: Gender, Power, and the Samurai Ideal

Challenging and Reinforcing Gender Norms

Tomoe Gozen’s legend operates within an interesting tension—she simultaneously challenges and reinforces traditional gender expectations:

She challenges norms by:

- Demonstrating female capacity for martial excellence

- Commanding troops in a male-dominated sphere

- Being described as equal to or superior to male warriors

- Taking active role in warfare rather than passive domestic role

She reinforces norms by:

- Being described as exceptionally beautiful—her femininity is maintained even as she performs masculine roles

- Serving a male master loyally rather than acting independently

- Being sent away from the final battle because Yoshinaka doesn’t want to die “with a woman”

- Disappearing from history rather than continuing as an independent warrior or leader

This ambiguity makes Tomoe’s legend culturally powerful—she can be interpreted different ways depending on the values being emphasized.

Embodying Bushidō Values

Tomoe exemplifies key principles of bushidō (the way of the warrior):

Loyalty (chū): Her devotion to Yoshinaka defines her story—she fights for him, refuses to abandon him, and finally obeys his command to leave only after demonstrating her loyalty through a final feat of valor.

Courage (yū): Her fearlessness in battle, willingness to face overwhelming odds, and personal combat prowess demonstrate the warrior’s courage.

Honor (meiyo): Her actions maintain and enhance her master’s honor and her own reputation.

Duty (gimu): She fulfills her obligations to her lord even when it means performing dangerous or difficult tasks.

These values weren’t gender-specific in samurai ideology—they applied to all warriors, male or female. Tomoe’s embodiment of them argues that women could exemplify samurai virtues as fully as men.

The Tragic Romantic Heroine

Many retellings of Tomoe’s story add romantic dimensions not explicit in original sources:

Tomoe and Yoshinaka are portrayed as lovers in many versions, adding emotional weight to her loyalty and his final command for her to flee.

Her disappearance becomes tragic not just because of military defeat but because of lost love.

Later life legends (her becoming a nun, marrying another warrior, or living in seclusion) all process the grief of her loss.

This romantic overlay made Tomoe’s story appealing to popular audiences while potentially diminishing her purely martial achievements by subordinating them to romantic motivations.

Modern Revival: Tomoe in Contemporary Culture

Feminist Reclamation

Since the mid-20th century, Tomoe Gozen has been reclaimed by feminist movements in Japan:

Women’s historians have researched onna-musha traditions, using Tomoe as an example to challenge narratives that portrayed pre-modern Japanese women as entirely subjugated.

Martial arts practitioners have invoked her as inspiration for women’s participation in martial traditions.

Gender equality advocates cite her as historical precedent for women in leadership and combat roles.

Educational materials have increasingly included her story when teaching about Japanese history, ensuring new generations know about female warriors.

However, this feminist reclamation faces complexities:

- How much can we claim as historical fact versus legend?

- Does emphasizing her exceptionalism actually reinforce the idea that women warriors were impossible rarities?

- Can a figure who ultimately served male authority be an unproblematic feminist icon?

Popular Culture Phenomenon

Tomoe Gozen has become ubiquitous in modern Japanese popular culture:

Video Games

Tomoe appears as a character in numerous games:

“Fate/Grand Order” features her as a summonable Servant, portraying her as a powerful warrior with tragic backstory.

“Samurai Warriors” series includes her as a playable character with impressive combat abilities.

“Nioh 2” and other historical action games incorporate her as character or reference her story.

These portrayals typically emphasize:

- Her martial prowess

- Her loyalty to Yoshinaka

- Her beauty

- Her tragic fate

Anime and Manga

Tomoe appears in or inspires characters in:

Historical anime depicting the Genpei War Fantasy manga where her legend is reinterpreted in new settings Character archetypes of the beautiful warrior woman clearly inspired by Tomoe’s legend

Film and Television

Japanese historical dramas (taiga dramas) periodically feature Tomoe as a significant character when covering the Genpei War period.

International productions occasionally reference her when depicting Japanese women warriors.

Academic Interest

Scholarly attention to Tomoe has increased:

Japanese historians continue debating her historical existence and the reliability of various sources.

Gender studies scholars analyze her legend as a text revealing cultural attitudes about women, warfare, and power.

Literary scholars examine how her story was constructed and transmitted through various genres.

Comparative historians place her alongside other historical women warriors from different cultures, analyzing similarities and differences in how such figures are remembered.

Tourism and Cultural Heritage

Sites associated with Tomoe have become tourist destinations:

The Kiso region in Nagano Prefecture promotes connections to Yoshinaka and Tomoe.

Museums and cultural centers include exhibits about women warriors in Japanese history, with Tomoe featured prominently.

Statues and monuments commemorate her in various locations.

Local festivals sometimes incorporate Tomoe into celebrations of regional history.

The Broader Question: Women, Warfare, and Historical Memory

Why Women Warriors Are Remembered (or Forgotten)

Tomoe Gozen’s story raises larger questions about how societies remember women who engaged in traditionally masculine activities:

Women warriors tend to be remembered when:

- They’re connected to famous male leaders (like Tomoe to Yoshinaka)

- Their stories can be romanticized or made to reinforce certain values

- They died tragically young (like Nakano Takeko)

- They combined martial prowess with beauty or femininity

They’re often forgotten when:

- They operated independently rather than supporting male leaders

- Their achievements challenged social hierarchies too directly

- They survived and lived ordinary lives afterward

- Documentation was sparse or lost

Tomoe’s survival in historical memory likely owes to multiple factors: her association with Yoshinaka, her appearance in “The Tale of the Heike,” the dramatic nature of her final exploit, and her mysterious disappearance that allowed later generations to imagine her fate.

The “Exceptional Woman” Problem

Tomoe’s legend presents what historians call the “exceptional woman” problem:

On one hand, recognizing and celebrating female achievement in male-dominated fields is important for challenging assumptions about women’s capabilities.

On the other hand, emphasizing how exceptional and unusual these women were can actually reinforce the notion that women’s participation in such activities was anomalous and therefore women generally couldn’t or shouldn’t do such things.

Modern discussions of Tomoe often navigate this tension—celebrating her while also noting she wasn’t entirely unique, that other women warriors existed, and that women’s historical agency was broader than often acknowledged.

Cultural Specificity of Women Warriors

Tomoe’s story is distinctly Japanese in several ways:

The onna-musha tradition provided a cultural framework for understanding women warriors that was specific to Japanese feudal society.

The emphasis on loyalty to lords rather than independent agency reflects Japanese political culture.

The aesthetic dimension—the emphasis on Tomoe’s beauty alongside her martial skill—reflects Japanese cultural values about beauty and martial prowess.

Her disappearance and possible later life as a nun connects to Buddhist influences on Japanese culture.

Comparing Tomoe to women warriors from other cultures—Joan of Arc, Boudicca, Mulan, etc.—reveals both universal themes (courage, loyalty, transgression of gender norms) and culture-specific elements in how such figures are portrayed and remembered.

Conclusion: History, Legend, and Cultural Power

Tomoe Gozen exists in the fascinating space between history and legend—a figure whose factual existence remains debated by scholars yet whose cultural reality is undeniable. Whether she fought exactly as described in “The Tale of the Heike,” whether she existed at all, or whether she was an entirely literary creation matters less than what her story has meant to Japanese culture across eight centuries.

Her legend has served multiple purposes across different eras: as an example of samurai loyalty and martial prowess in medieval tales, as a symbol of traditional Japanese warrior spirit in nationalist narratives, as inspiration for physical education and martial training for women in the modern period, and as a feminist icon challenging gender limitations in contemporary culture.

The historical context reveals that women warriors, while uncommon, were not impossible in medieval Japan. The onna-musha tradition, naginata training for upper-class women, and documented examples of other female warriors suggest that Tomoe—if she existed—was exceptional but not entirely outside the realm of possibility.

Her enduring cultural presence demonstrates how legendary figures can shape cultural identity and values across centuries. Tomoe has been continuously reinterpreted—through Noh theater, ukiyo-e prints, kabuki plays, historical novels, feminist reclamation, and modern popular culture—each era finding different meanings in her story while maintaining certain core elements: exceptional martial skill, unwavering loyalty, beauty combined with ferocity, and tragic or mysterious fate.

For modern audiences, Tomoe Gozen raises important questions: How do we balance appreciation for historical female achievement with awareness of how exceptional women’s stories can be used to marginalize ordinary women’s histories? How do we interpret legendary figures when historical evidence is limited? What does it mean that Tomoe’s story emphasizes both her martial equality with men and her ultimate subordination to male authority?

Perhaps the most important insight from Tomoe’s legend is that historical memory is never simply about facts—it’s about the stories cultures tell themselves about their values, their possibilities, and their identities. Tomoe Gozen, whether historical warrior or literary creation, has been one of the stories Japanese culture has told itself about courage, loyalty, beauty, feminine strength, and the complex relationships between gender and power.

Eight centuries after she allegedly rode into battle, Tomoe Gozen remains a powerful cultural presence—studied by historians, celebrated in popular culture, invoked in feminist discourse, and continuing to inspire new interpretations and artistic representations. This enduring fascination suggests that her story speaks to something fundamental about human aspirations and the desire to imagine a world where courage and skill can transcend social limitations.

Whether she existed exactly as described matters less than this: her legend has given countless people—particularly women—a historical figure to identify with, to find inspiration in, and to use as evidence that women’s exclusion from martial and leadership roles was never as total or inevitable as often portrayed. In this sense, Tomoe Gozen’s greatest victory may not have been on any battlefield, but in the cultural imagination, where her story continues to challenge, inspire, and provoke thought about gender, power, and possibility.

Additional Resources

For those interested in learning more about Tomoe Gozen and women warriors in Japanese history:

- The Samurai Archives provides historical context on the Genpei War and samurai culture

- Women in World History Curriculum offers educational resources on women’s roles in various historical periods including feudal Japan