Table of Contents

Who Was Nzinga of Ndongo? Complete Guide to Angola’s Warrior Queen and Her Resistance Against Portuguese Colonization

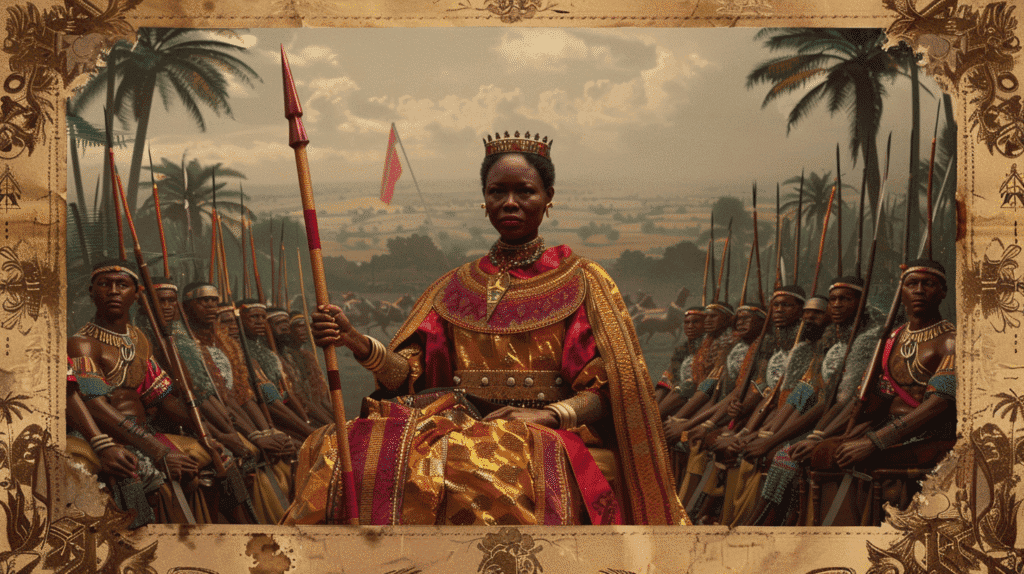

Queen Nzinga Mbande of Ndongo and Matamba (c. 1583-1663) stands as one of Africa’s most formidable leaders and a towering figure in the history of resistance against European colonization. For nearly four decades during the 17th century, this remarkable woman ruled two kingdoms in what is now Angola, employing brilliant military tactics, sophisticated diplomacy, and strategic alliances to preserve her people’s independence against relentless Portuguese expansion and the devastating Atlantic slave trade.

Her story transcends typical narratives of African colonization. Nzinga was not a passive victim of European imperialism but an active political agent who negotiated with Portuguese governors as an equal, formed strategic alliances with Dutch rivals of Portugal, led armies in guerrilla warfare, and maintained her kingdoms’ sovereignty through decades when most African states were succumbing to European conquest. She combined traditional African political authority with adaptive strategies learned from observing European tactics, creating a hybrid approach that frustrated Portuguese ambitions for territorial control.

Born into the royal family of Ndongo around 1583, Nzinga witnessed firsthand how Portuguese slave traders and soldiers destabilized African societies. She learned early that survival required both military strength and diplomatic finesse—lessons she would apply throughout her long reign. Her famous 1622 negotiation in Luanda, where she commanded respect from Portuguese authorities through symbolic gestures and political acumen, demonstrated the intelligence and determination that would characterize her leadership.

This comprehensive guide explores every dimension of Nzinga’s extraordinary life: her royal education and path to power, her innovative military strategies against Portuguese forces, her complex relationship with Christianity and European culture, her navigation of gender expectations in a male-dominated political world, and her enduring legacy as a symbol of African resistance. Understanding Nzinga means understanding how African leaders confronted colonialism not with passive acceptance but with sophisticated resistance strategies that sometimes succeeded in preserving independence for generations.

Why Queen Nzinga’s Story Matters for Understanding African History

Nzinga’s life illuminates crucial aspects of African history that are often overlooked or misunderstood. First, her story challenges the persistent myth that European colonization of Africa was inevitable or that African societies passively accepted European domination. Nzinga’s four-decade resistance demonstrates that African leaders employed complex political, military, and diplomatic strategies that sometimes succeeded in preventing or delaying European conquest.

Second, her leadership reveals the Atlantic slave trade’s devastating complexity. Nzinga fought against Portuguese attempts to enslave her people while navigating an economic system where participating in the slave trade (selling war captives from other groups) provided access to firearms and European goods necessary for military survival. This moral complexity reflects the impossible choices African leaders faced—rejecting the slave trade entirely meant losing access to weapons needed for defense, while participating strengthened a system destroying African societies.

Third, Nzinga’s story provides crucial perspectives on women’s leadership in African history. As a woman ruling in a predominantly patriarchal society, she had to negotiate gender expectations while asserting political authority. Her strategies—sometimes adopting male titles and dress, sometimes leveraging femininity strategically—demonstrate how women leaders navigated constraints to exercise effective power.

For contemporary African identity, particularly in Angola, Nzinga remains a powerful symbol. When Angola achieved independence from Portugal in 1975 after a brutal liberation war, nationalist leaders explicitly connected their struggle to Nzinga’s 17th-century resistance. Her image appears on Angolan currency, monuments, and in cultural celebrations, representing continuity between historical resistance and modern independence movements.

Understanding Nzinga also illuminates broader patterns in colonial encounters—how African leaders formed strategic alliances with European powers to counter other European powers, how African and European political systems interacted and influenced each other, and how local politics and global forces intersected in shaping colonial outcomes.

The Kingdom of Ndongo and Central Africa in Crisis

To understand Nzinga’s achievements, we must first understand the political landscape and challenges she inherited.

Ndongo: A Kingdom Under Siege

The Kingdom of Ndongo occupied territory in what is now northern Angola, south of the more powerful Kingdom of Kongo. Founded in the 15th or 16th century by the Mbundu people, Ndongo was a centralized state with the ruler bearing the title ngola (from which “Angola” derives).

By the time Nzinga was born around 1583, Ndongo faced existential crisis. Portuguese had established a permanent presence in Luanda in 1575, initially as a trading post but increasingly as a base for territorial expansion. Portuguese soldiers, armed with firearms and cannons, pressured Ndongo militarily. Portuguese-allied African groups conducted slave raids into Ndongo territories. The kingdom’s economy and social fabric were unraveling under combined pressures of warfare, slave raiding, and Portuguese economic disruption.

Ndongo’s political structure featured the ngola as supreme ruler, supported by nobles, military commanders, and territorial governors. The kingdom controlled valuable trade routes and agricultural lands, making it attractive to Portuguese seeking both territorial control and access to enslaved laborers for Brazilian plantations.

The Portuguese Colonial Project in Angola

Portuguese interest in Central Africa initially focused on trade—gold, ivory, and increasingly enslaved people. But by the late 16th century, Portuguese colonial strategy shifted toward territorial conquest and establishing settler colonies modeled on Brazil.

The Atlantic slave trade was transforming Portuguese priorities. Brazil’s sugar plantations created insatiable demand for enslaved laborers, and Angola was positioned as the primary source. Portuguese authorities in Luanda organized slave-raiding expeditions, paid African allies to capture people for sale, and attempted to control territories where they could directly exploit populations.

Portuguese military advantages included firearms, cannons, professional military organization, and networks of African allies willing to cooperate in exchange for trade goods and protection from rival African groups. But Portuguese forces were small—rarely more than a few hundred soldiers—meaning they depended heavily on African auxiliaries and political divisions among African kingdoms.

The Mbundu People and Regional Politics

The Mbundu people formed Ndongo’s core population. They were agricultural societies organized into villages and chiefdoms, with the ngola exercising varying degrees of control over these local authorities. Mbundu society featured clear social hierarchies, with nobles, commoners, and slaves forming distinct classes.

Traditional Mbundu religion focused on ancestor worship and nature spirits, though by Nzinga’s time, Christian influences were beginning to penetrate through Portuguese missionary activity. Religious authority and political power were interconnected, with rulers needing to maintain proper relationships with spiritual forces to legitimize their governance.

The region’s political landscape featured multiple competing kingdoms and chiefdoms—Kongo to the north, Matamba to the east, various smaller polities surrounding Ndongo. These groups competed for trade routes, agricultural lands, and political dominance, creating opportunities for Portuguese to exploit divisions through strategic alliances.

The Slave Trade’s Devastating Impact

By the early 17th century, the slave trade was fundamentally destabilizing Central African societies. The scale was enormous—tens of thousands of people annually were captured and shipped from Angolan ports to the Americas. This depopulation weakened kingdoms militarily and economically, disrupted agriculture, separated families, and created pervasive insecurity.

The trade also created perverse incentives. African leaders could acquire firearms and European goods by selling captives, but refusing to participate meant being militarily disadvantaged against neighbors who did participate. This dynamic created a devastating cycle where the trade strengthened itself—those who resisted were conquered by those who cooperated, further expanding the trade.

For leaders like Nzinga, the slave trade presented impossible dilemmas: participate to gain military resources while contributing to African societies’ destruction, or refuse and face military disadvantage that might lead to your own people being enslaved by others.

Nzinga’s Early Life: Education for Power

The woman who would become one of Africa’s most formidable rulers received education and training that prepared her for leadership, though her path to power would prove difficult and contested.

Royal Birth and Family Background

Nzinga Mbande was born around 1583 to Ngola Kiluanji kia Samba, king of Ndongo, and one of his wives. As a member of the royal family, Nzinga was part of the kingdom’s elite, with access to education and political training usually reserved for males who might inherit power.

Her name “Nzinga” (also spelled Njinga or Jinga) derived from the Kimbundu word meaning “to twist” or “to wrap,” reportedly because the umbilical cord was wrapped around her neck at birth—a sign some interpreted as indicating she would be proud, strong-willed, and destined for significance.

Nzinga had siblings, including a brother who would become king and a sister who would later serve as an important political ally. Royal family dynamics in Ndongo involved both cooperation and competition, with various children potentially positioned for succession and family members sometimes competing for power.

Education in Statecraft and Warfare

Unlike in many patriarchal societies where women received limited education, royal women in Ndongo could receive substantial training in politics, military arts, and governance. Nzinga benefited from this tradition, learning about diplomacy, military strategy, religious practices, legal traditions, and the arts of negotiation and political maneuvering.

She reportedly received weapons training and learned military tactics—unusual for women but not unprecedented for royal women who might need to defend themselves or their territories. This military education would prove crucial during her decades of warfare against Portuguese forces.

Nzinga also learned about Portuguese culture, language, and diplomatic practices—knowledge that would serve her throughout her political career. She understood that effective resistance required comprehending the enemy’s methods, motivations, and weaknesses.

Her education emphasized both traditional Mbundu knowledge and practical understanding of the changing political landscape created by Portuguese presence. This combination of traditional wisdom and adaptive learning characterized her approach throughout her reign.

Growing Up During Portuguese Expansion

Nzinga came of age during a period of escalating Portuguese pressure. She witnessed Portuguese military campaigns against Ndongo, saw how slave raids devastated communities, and observed her father’s struggles to maintain independence while managing Portuguese demands.

These formative experiences shaped her understanding of what was at stake. She saw that Portuguese ambitions went beyond trade—they wanted territorial control and access to people for enslavement. She learned that Portuguese respected strength and perceived weakness invited aggression.

She also observed how some African leaders collaborated with Portuguese while others resisted, and she formed judgments about which strategies worked and which failed. This education through observation complemented her formal training, creating a politically sophisticated understanding of how to navigate the challenges she would face as a leader.

The 1622 Luanda Negotiations: Nzinga’s Diplomatic Breakthrough

Nzinga’s first major appearance in recorded history came through a diplomatic mission that demonstrated her remarkable political skills and established her reputation.

The Context: Ndongo in Crisis

By 1622, Ndongo was in desperate straits under the rule of Nzinga’s brother, Ngola Mbandi. Portuguese forces had captured key territories, including the strategic fortress of Ambaca. Tributary chiefs were defecting to Portuguese protection. The kingdom was fracturing, and military resistance was failing.

Mbandi, proving unequal to the crisis, needed skilled diplomacy to secure peace terms that might preserve some autonomy. He chose his sister Nzinga for this crucial mission—recognition of her political abilities despite her gender and despite apparent tensions between the siblings.

The mission’s objectives were survival: negotiate a treaty stopping Portuguese military advances, secure return of captured territories if possible, and buy time for Ndongo to recover and reorganize. Nzinga would need to negotiate from weakness while projecting strength—an extraordinarily difficult diplomatic challenge.

The Famous Chair Incident

When Nzinga arrived in Luanda to meet Portuguese Governor João Correia de Sousa, she faced immediate symbolic challenge. The governor sat in a chair while offering Nzinga only a floor mat—a deliberate slight indicating inferior status and Portuguese dominance.

Nzinga’s response became legendary. She ordered one of her attendants to kneel on all fours, and she sat on the attendant’s back, creating an improvised throne that equalized the seating arrangement. This gesture asserted her dignity and equal status without directly insulting the governor or provoking conflict.

The incident revealed Nzinga’s political sophistication. She understood that ceremony and symbolism mattered in diplomatic encounters—accepting inferior seating would signal acceptance of inferior status. Her creative solution resolved the immediate problem while demonstrating intelligence and assertiveness that earned Portuguese respect.

While this story might seem minor, it was politically crucial. Nzinga established herself as a leader who commanded respect, setting the tone for negotiations and signaling that Ndongo would not accept dictated terms without negotiation.

The Treaty and Strategic Conversion

The negotiations produced a treaty with several key provisions: Portuguese would withdraw from some occupied territories, both sides would return prisoners and deserters, Ndongo would allow Portuguese missionaries to operate in the kingdom, and formal peace would be established between Ndongo and Portuguese Angola.

As part of the negotiations, Nzinga agreed to convert to Christianity, taking the baptismal name Ana de Sousa after the governor’s wife who served as her godmother. This conversion was clearly strategic—Christianity would facilitate diplomatic relations and potentially secure Portuguese recognition of her legitimacy as a leader.

The treaty was a reasonable compromise given Ndongo’s weak position. It didn’t restore Ndongo to its former power but did stop immediate Portuguese military advances and provided breathing space. For Nzinga personally, the mission established her reputation as a skilled diplomat who could negotiate with Europeans as an equal.

Return to Ndongo and Succession Crisis

When Nzinga returned to Ndongo, her brother Mbandi’s position was precarious. The treaty had bought time but not solved fundamental problems. Mbandi apparently viewed Nzinga as a potential rival—some sources suggest he had killed her son to prevent future succession claims.

When Mbandi died in 1624 (circumstances remain unclear—possibly suicide, possibly poisoning), Nzinga moved quickly to seize power. She claimed to rule as regent for Mbandi’s young son, but she effectively made herself queen, taking the title ngola despite traditional norms favoring male rulers.

Her ascension was contested. Some nobles opposed a female ruler on principle. Portuguese were uncertain about recognizing her authority. But through a combination of political maneuvering, military force, and the reputation she had established through her diplomatic mission, Nzinga consolidated power and became Ndongo’s undisputed ruler.

Military Resistance: Fighting Portuguese Conquest

Once secure in power, Nzinga immediately confronted the Portuguese threat militarily, developing strategies that would frustrate European conquest for decades.

Initial Conflicts and Portuguese Betrayal

Despite the 1622 treaty, peace didn’t last. Portuguese violated treaty provisions, refused to return all occupied territories, and continued supporting slave raids into Ndongo lands. By 1626, open warfare resumed.

Portuguese military advantages were formidable: firearms and artillery that African forces couldn’t match, professional military organization creating disciplined units, fortified positions difficult to assault, and networks of African allies providing local knowledge and additional troops.

Nzinga needed strategies to counter these advantages without the resources for conventional warfare. She couldn’t match Portuguese firepower in set-piece battles, and defending fixed positions meant being vulnerable to Portuguese artillery. She needed different approaches.

Guerrilla Warfare and Mobile Tactics

Nzinga pioneered guerrilla warfare strategies that maximized her advantages while minimizing Portuguese strengths. Her forces operated from bases in difficult terrain—forests, mountains—where Portuguese columns couldn’t easily pursue. They conducted hit-and-run raids on Portuguese settlements and supply convoys, then withdrew before Portuguese could organize counterattacks.

This mobile warfare required keeping armies supplied and organized while constantly moving, maintaining intelligence networks to track Portuguese movements, preserving warrior morale despite years of hardship without decisive victories, and preventing Portuguese from cutting off resources or trapping forces in unfavorable battles.

Nzinga personally participated in military campaigns, reportedly fighting alongside warriors well into her 50s and 60s. This personal leadership was crucial for maintaining morale and demonstrating her commitment to the struggle.

The Strategic Retreat to Matamba

By 1626, Portuguese military pressure on Ndongo became overwhelming. Rather than fight a losing battle for Ndongo’s traditional territories, Nzinga made a bold strategic decision: retreat eastward and conquer the Kingdom of Matamba, establishing a new power base beyond immediate Portuguese reach.

The conquest and occupation of Matamba was a remarkable achievement requiring military force to defeat Matamba’s existing ruler, diplomatic skill to integrate Matamba subjects with Ndongo refugees, administrative capability to govern a newly combined kingdom, and strategic vision to recognize that retreat could actually strengthen her position.

From Matamba, Nzinga continued resisting Portuguese from a stronger position. The kingdom controlled important trade routes, had productive agricultural lands to support armies, and was positioned beyond Portuguese forces’ easy reach. Matamba became the center of sustained resistance for decades.

Alliances, Tactics, and Adaptation

Throughout her military campaigns, Nzinga demonstrated remarkable adaptability. She formed alliances with neighboring African groups opposed to Portuguese expansion, employed African military traditions (ambush tactics, rapid movement, knowledge of local terrain) effectively, gradually acquired and learned to use firearms despite limited access, and adapted tactics based on experience and observation of what worked.

Her armies included both male and female warriors, with some accounts suggesting she organized women’s military units—unusual but reflecting both practical necessity (needing all available fighters) and her willingness to challenge gender conventions when militarily advantageous.

She also understood psychological warfare, using symbolic displays and strategic communications to intimidate enemies and maintain her people’s morale. Her reputation as a fierce, uncompromising opponent served strategic purposes—Portuguese learned that conquering territories where Nzinga had influence would be costly and difficult.

The Dutch Alliance: Strategic Opportunism

In the 1640s, Nzinga formed a strategic alliance with the Dutch West India Company that temporarily shifted the balance of power in Angola and demonstrated her sophisticated understanding of European rivalries.

Dutch Capture of Luanda and New Opportunities

In 1641, the Dutch West India Company captured Luanda from Portuguese, part of broader Dutch-Portuguese competition for colonial territories and trade routes. The Dutch wanted to control the slave trade and establish their own colonial presence in Angola.

For Nzinga, Dutch presence created opportunities. The Dutch were enemies of her Portuguese enemies, making them potential allies. Dutch possessed military technology and resources that could strengthen resistance to Portuguese. An alliance could provide access to firearms, ammunition, and potential military support against Portuguese forces.

Nzinga quickly opened negotiations with Dutch authorities, demonstrating her strategic flexibility and understanding of how to exploit European rivalries for African advantage.

The Alliance in Practice

The Dutch-Nzinga alliance achieved significant successes in the 1640s. Coordinated Dutch-Nzinga attacks captured Portuguese-held territories and threatened Portuguese control of interior regions. Dutch provided firearms, ammunition, and some direct military support to Nzinga’s forces. The alliance created genuine possibility of expelling Portuguese from Angola entirely.

However, the alliance also revealed contradictions and limitations. The Dutch were slave traders themselves, interested in controlling the slave trade rather than ending it. The alliance required Nzinga’s cooperation in providing enslaved people for Dutch ships—compromising her opposition to the slave trade. Dutch priorities were commercial rather than supporting African independence—they saw Nzinga as useful ally but not equal partner.

Portuguese Reconquest and Alliance Collapse

In 1648, Portuguese forces from Brazil recaptured Luanda, ending Dutch presence in Angola. The Dutch-Nzinga alliance collapsed, leaving Nzinga facing Portuguese forces alone again but having benefited from years of Dutch military support that had strengthened her position.

The alliance’s failure demonstrated the limits of relying on European allies whose interests only partially aligned with African independence. Dutch had helped when it served their purposes but abandoned Nzinga when their own position in Angola became untenable.

Nevertheless, the alliance had achieved important objectives: weakening Portuguese military position, acquiring weapons and military knowledge, demonstrating to Portuguese that Nzinga could form alternative alliances if Portuguese pressured too hard, and buying years of relative security while Portuguese were distracted by Dutch presence.

Religion, Gender, and Political Authority

Nzinga navigated complex issues of religious identity and gender expectations while maintaining political authority—demonstrating sophisticated understanding of how to leverage both for political advantage.

Strategic Christianity and Religious Flexibility

Nzinga’s relationship with Christianity was complex and evolved over her life. Her 1622 conversion was clearly strategic, facilitating diplomatic relations with Catholic Portuguese. But her Christian practice varied based on political circumstances—sometimes she emphasized Christianity when dealing with Europeans or Christian subjects, other times she maintained traditional African religious practices when politically advantageous.

This religious flexibility frustrated Portuguese missionaries who wanted genuine conversion, but it demonstrated Nzinga’s understanding of religion as political tool. She used Christianity to legitimate her rule among Christian subjects and European allies while maintaining traditional religious authority that legitimated her rule among subjects following traditional beliefs.

Later in life, particularly after the 1656 peace treaty with Portugal, Nzinga apparently embraced Christianity more seriously—inviting missionaries, building churches, attending mass regularly, and possibly experiencing genuine spiritual transformation in her final years.

Navigating Gender Expectations

As a woman ruling in a predominantly patriarchal society, Nzinga faced constant challenges to her authority based on gender. She employed multiple strategies to navigate these constraints:

Adopting male titles and symbols: She sometimes used the male title ngola rather than a female equivalent, dressed in male clothing when commanding armies, and adopted other male-associated symbols of authority.

Strategic femininity: Other times she emphasized her femininity, using it to her advantage in diplomatic contexts or when dealing with European men whose gender expectations she could manipulate.

Demonstrating military prowess: By personally participating in military campaigns and demonstrating courage in battle, she proved she possessed traditionally masculine virtues.

Political marriages: She contracted strategic marriages that served political purposes while asserting her authority to make dynastic decisions.

Building female power networks: She elevated women to important positions, creating a court where women wielded significant influence.

These strategies demonstrated that effective leadership required adapting to gender expectations rather than simply defying them. Nzinga understood when to challenge norms directly and when to work within them strategically.

The 1656 Peace Treaty and Final Years

After decades of warfare, Nzinga’s final years brought a negotiated peace that preserved Matamba’s independence while normalizing relations with Portugal.

The Treaty and Its Significance

The 1656 peace treaty between Nzinga and Portugal ended decades of hostilities. Key provisions included: Nzinga would return Portuguese prisoners and deserters, allow Christian missionaries to operate in Matamba, recognize Portuguese presence in coastal Angola, and establish trade relations. In exchange, Portugal recognized Nzinga’s sovereignty over Matamba, ceased military operations against her territories, and granted favorable trade terms.

Some historians interpret this treaty as Nzinga’s surrender, but others view it as achieving her fundamental goal: preserving her kingdom’s independence. She had fought for decades to prevent Portuguese conquest of Matamba, and the treaty formalized Portuguese recognition of her sovereignty.

Both sides were exhausted from decades of warfare. Portuguese had failed to conquer Matamba despite sustained efforts. Nzinga’s people had suffered enormously from constant warfare. Peace served both parties’ interests.

Religious Deepening and Legacy Planning

Nzinga’s final years showed apparent deepening of Christian faith. She invited Capuchin missionaries, built churches, attended mass regularly, and enforced Christian practices at court. Whether this represented genuine spiritual conversion or deathbed insurance is unknowable, but contemporary observers described her as devoutly religious in her final years.

She also worked to secure succession, though accounts conflict about her designated heir. Ensuring stable transition was crucial for preserving Matamba’s independence after her death—a primary concern for a leader who had spent four decades building and defending her kingdom.

Death and Immediate Legacy

Nzinga died on December 17, 1663, at approximately 80 years old—a remarkable age given her difficult life of constant warfare, political struggles, and physical hardships. She had ruled for 39 years, making her one of the longest-reigning African monarchs of her era.

Her death marked the end of the most effective resistance to Portuguese colonization in Angola. While other leaders continued opposing Portuguese, none matched Nzinga’s combination of military skill, diplomatic sophistication, political longevity, and success in preserving independence.

After her death, Matamba’s stability declined. Her successors lacked her political abilities, and internal disputes weakened the kingdom. Portuguese gradually increased their influence, though Matamba maintained nominal independence for decades more.

Legacy: From Historical Figure to National Symbol

Nzinga’s legacy has evolved dramatically across four centuries, reflecting changing political contexts and the uses to which her memory has been put.

Colonial Portuguese Narratives

During centuries of Portuguese colonial rule in Angola (1575-1975), Portuguese authorities constructed narratives minimizing or denigrating Nzinga’s resistance. Colonial histories portrayed her as a curiosity or savage—downplaying her achievements to justify Portuguese conquest as bringing “civilization” to supposedly backward peoples.

These narratives served ideological purposes: if African leaders were incompetent or barbaric, Portuguese colonization could be justified as beneficial. Nzinga had to be diminished to support this colonial mythology.

However, among Angolan peoples, oral traditions preserved different memories. Stories passed through generations remembered Nzinga as a hero who had fought for independence, maintained dignity against foreign oppression, and demonstrated that Africans could resist European power effectively.

Angolan Independence Movement

When Angolan nationalist movements emerged in the mid-20th century, they invoked Nzinga as historical precedent for their struggle. Leaders like Agostinho Neto (Angola’s first president) and organizations like the MPLA explicitly connected their liberation war (1961-1975) to Nzinga’s 17th-century resistance.

Nzinga became a symbol of Angolan nationalism representing: indigenous resistance to foreign domination, the legitimacy of fighting for independence, pride in African history and capabilities, and continuity between historical struggles and contemporary liberation movements.

After independence in 1975, the new Angolan government celebrated Nzinga as a founding figure. Her image appeared on currency and stamps, streets and institutions were named after her, monuments honored her memory, and her story was taught as part of Angolan national identity.

Pan-African and Diaspora Memory

Beyond Angola, Nzinga became important to pan-African movements and African diaspora communities. She represented: African resistance to colonialism from its earliest stages, evidence that African leaders could match European opponents in political and military skill, powerful female leadership challenging gender stereotypes, and pride in African heritage and capabilities.

African American communities, particularly those engaged with African heritage, embraced Nzinga as an inspirational figure. She appeared in literature, art, and cultural celebrations as a symbol of Black pride and resistance to oppression—connecting African and diaspora experiences of fighting against domination.

Academic Scholarship and Complexity

Modern historical scholarship has worked to develop more nuanced understanding moving beyond both colonial denigration and uncritical celebration. Recent research emphasizes: her strategic sophistication in both military and diplomatic affairs, the impossible moral choices she faced regarding the slave trade, the importance of understanding her within Central African political contexts, and the need to recognize both her achievements and her compromises.

This scholarship reveals a more complex figure—a brilliant leader making difficult decisions under extreme pressure, achieving remarkable successes while also making moral compromises, and ultimately preserving her people’s independence through decades of determined resistance despite overwhelming challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions About Queen Nzinga

Was Nzinga’s military resistance actually successful?

Yes, by the most important measure—she maintained Matamba’s independence for nearly four decades despite sustained Portuguese pressure. While she never decisively defeated Portuguese militarily, she prevented conquest and secured Portuguese recognition of her sovereignty. Given the resources and challenges she faced, this represents extraordinary success.

Did she really sit on an attendant during the 1622 negotiations?

This famous story appears in multiple Portuguese sources from the period, making it likely authentic, though exact details may have been embellished. What’s certain is that Nzinga understood ceremonial politics and used symbolism strategically to assert equal status with Portuguese authorities.

How should we understand her relationship with the slave trade?

This remains the most morally complex aspect of her legacy. Nzinga participated in slavery while fighting to protect her people from enslavement—a contradiction reflecting the impossible structural constraints African leaders faced. Complete rejection of the trade would have meant losing access to firearms necessary for defense, while participation strengthened a system destroying African societies. Historical understanding requires acknowledging this complexity.

Was she really a Christian or was it strategic?

Her initial 1622 conversion was clearly strategic. Her later life showed more consistent Christian practice, suggesting possible genuine faith development. Most likely, her Christianity mixed strategic calculations with evolving spiritual engagement—not unusual for political conversions.

Why was a woman able to rule in 17th-century Africa?

While patriarchal norms were strong, Central African political systems weren’t as rigidly gendered as often assumed. Royal women could wield significant power, and capable women could sometimes become rulers. Nzinga’s ascension was contested but not unprecedented. Her success owed to political skill, military support, and the crisis context that prioritized effective leadership over gender conventions.

What happened to her kingdoms after her death?

Matamba maintained formal independence for decades but gradually weakened under less capable successors. Portuguese influence increased through economic penetration and political manipulation. By the 18th century, Matamba had lost effective sovereignty, though it was never formally conquered in the way Nzinga had prevented during her lifetime.

Conclusion: A Leader Who Changed History

Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba stands as one of history’s most remarkable leaders—a brilliant military strategist who pioneered guerrilla warfare tactics, a sophisticated diplomat who negotiated with European powers as an equal, and a determined monarch who preserved her kingdoms’ independence for four decades against overwhelming Portuguese military and economic pressure.

Her achievements were extraordinary given the challenges she faced: Portuguese military advantages in firearms and organization, the Atlantic slave trade’s economic and political pressures, gender discrimination in a patriarchal political system, limited resources compared to her European opponents, and an era when most African societies were succumbing to European colonization.

That she succeeded in maintaining independence testifies to her exceptional abilities. She combined military innovation with diplomatic sophistication, strategic flexibility with determined resistance, traditional African authority with adaptive learning from European methods, and personal courage with political calculation.

Nzinga’s legacy is complex. She participated in the slave trade while fighting to protect her people from enslavement. She converted to Christianity for political advantage while maintaining traditional spiritual practices. She challenged gender norms while sometimes working within them strategically. These contradictions don’t diminish her achievements—they reflect the impossible choices leaders faced navigating between survival and principles in an era of violent colonial expansion.

For modern Angola and beyond, Nzinga remains a powerful symbol of resistance against oppression, African political sophistication, and women’s leadership capabilities. Her story challenges narratives of European superiority and African passivity, demonstrating that colonial encounters involved sophisticated African agency and that outcomes weren’t predetermined but resulted from specific decisions, alliances, and contingencies.

Four centuries after her death, Queen Nzinga’s greatest legacy may be simply this: she refused to surrender. For forty years, despite every pressure, every military disadvantage, every impossible circumstance, she maintained resistance and preserved her people’s independence. That determination continues inspiring people facing their own struggles against oppression, making her not just a historical figure but an enduring symbol of the human capacity to resist domination and fight for freedom against overwhelming odds.